Magnetic survey (archaeology)

The chief limitation of magnetometer survey is that subtle features of interest may be obscured by highly magnetic geologic or modern materials.

Environmental processes such as repeated vegetation fires and redox reactions caused by wetting and drying of the soil convert iron compounds to oxide maghemite (y-Fe2O3).

[2] Roads and structures are also visible from magnetic surveys since they can be detected because the susceptibility of the subsoil material used in their construction is lower than the surrounding topsoil.

The subsequent introduction of Fluxgate and cesium vapor magnetometers improved sensitivity, and greatly increased sampling speed, making high resolution surveys of large areas practical.

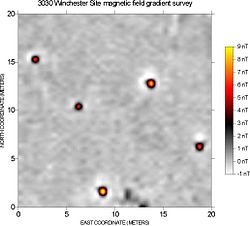

[5] Magnetometers react very strongly to iron and steel, brick, burned soil, and many types of rock, and archaeological features composed of these materials are very detectable.

Many types of sites and features have been successfully mapped with magnetometers, ranging from very ephemeral prehistoric campsites to large urban centers.

This utilizes a container full of hydrogen-rich liquids (commonly kerosene or methanol) that, when agitated by a direct current (DC) or Radio Frequency (RF), cause the electrons to become energized and transfer that energy to the protons due to the Overhauser Effect, basically turning them into dipole magnets.

[7] In maritime archaeology, these are often used to map the geology of wreck sites and determine the composition of magnetic materials found on the seafloor.

An Overhauser magnetometer (PPM) was used in 2001 to map Sebastos (the harbor of Caesarea Maritima) and helped to identify components of the Roman concrete.