Magnetism

[vague] The force of a magnet on paramagnetic, diamagnetic, and antiferromagnetic materials is usually too weak to be felt and can be detected only by laboratory instruments, so in everyday life, these substances are often described as non-magnetic.

[3] The word magnet comes from the Greek term μαγνῆτις λίθος magnētis lithos,[4] "the Magnesian stone, lodestone".

[6] The ancient Indian medical text Sushruta Samhita describes using magnetite to remove arrows embedded in a person's body.

[7] In ancient China, the earliest literary reference to magnetism lies in a 4th-century BC book named after its author, Guiguzi.

[8] The 2nd-century BC annals, Lüshi Chunqiu, also notes: "The lodestone makes iron approach; some (force) is attracting it.

"[10] The 11th-century Chinese scientist Shen Kuo was the first person to write—in the Dream Pool Essays—of the magnetic needle compass and that it improved the accuracy of navigation by employing the astronomical concept of true north.

In 1282, the properties of magnets and the dry compasses were discussed by Al-Ashraf Umar II, a Yemeni physicist, astronomer, and geographer.

Jean-Baptiste Biot and Félix Savart, both of whom in 1820 came up with the Biot–Savart law giving an equation for the magnetic field from a current-carrying wire.

In 1831, Michael Faraday discovered that a time-varying magnetic flux induces a voltage through a wire loop.

In 1905, Albert Einstein used Maxwell's equations in motivating his theory of special relativity,[13] requiring that the laws held true in all inertial reference frames.

Gauss's approach of interpreting the magnetic force as a mere effect of relative velocities thus found its way back into electrodynamics to some extent.

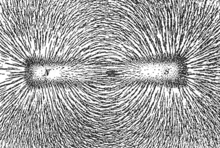

Ordinarily, the enormous number of electrons in a material are arranged such that their magnetic moments (both orbital and intrinsic) cancel out.

The magnetic behavior of a material depends on its structure, particularly its electron configuration, for the reasons mentioned above, and also on the temperature.

At high temperatures, random thermal motion makes it more difficult for the electrons to maintain alignment.

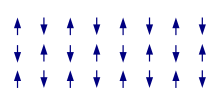

Thus, even in the absence of an applied field, the magnetic moments of the electrons in the material spontaneously line up parallel to one another.

When the material is cooled, this domain alignment structure spontaneously returns, in a manner roughly analogous to how a liquid can freeze into a crystalline solid.

In an antiferromagnet, unlike a ferromagnet, there is a tendency for the intrinsic magnetic moments of neighboring valence electrons to point in opposite directions.

When a ferromagnet or ferrimagnet is sufficiently small, it acts like a single magnetic spin that is subject to Brownian motion.

A variation on this was achieved experimentally by arranging the atoms in a triangular moiré lattice of molybdenum diselenide and tungsten disulfide monolayers.

Applying a weak magnetic field and a voltage led to ferromagnetic behavior when 100–150% more electrons than lattice nodes were present.

Electromagnets usually consist of a large number of closely spaced turns of wire that create the magnetic field.

Electromagnets are widely used as components of other electrical devices, such as motors, generators, relays, solenoids, loudspeakers, hard disks, MRI machines, scientific instruments, and magnetic separation equipment.

Maxwell's equations, which simplify to the Biot–Savart law in the case of steady currents, describe the origin and behavior of the fields that govern these forces.

Certain grand unified theories predict the existence of monopoles which, unlike elementary particles, are solitons (localized energy packets).

Some materials in living things are ferromagnetic, though it is unclear if the magnetic properties serve a special function or are merely a byproduct of containing iron.

In the years after 1820, André-Marie Ampère carried out numerous experiments in which he measured the forces between direct currents.

However, Maxwell's electrodynamics is not fully compatible with the work of Ampère, Gauss and Weber in the quasi-static regime.

While heuristic explanations based on classical physics can be formulated, diamagnetism, paramagnetism and ferromagnetism can be fully explained only using quantum theory.

The "singlet state", i.e. the − sign, means: the spins are antiparallel, i.e. for the solid we have antiferromagnetism, and for two-atomic molecules one has diamagnetism.

The explanation of the phenomena is thus essentially based on all subtleties of quantum mechanics, whereas the electrodynamics covers mainly the phenomenology.