Mandan

The Mandan historically lived along both banks of the Upper Missouri River and two of its tributaries—the Heart and Knife rivers—in present-day North and South Dakota.

They established permanent villages featuring large, round, earth lodges, some 40 feet (12 m) in diameter, surrounding a central plaza.

Nearby Siouan speakers had exonyms similar to Mantannes in their languages, for instance, Teton Miwáthaŋni or Miwátąni, Yanktonai Miwátani, Yankton Mawátani or Mąwátanį, Dakota Mawátąna or Mawátadą, etc.

The name Mi-ah´ta-nēs recorded by Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden in 1862 reportedly means "people on the river bank", but this may be a folk etymology.

Various other terms and alternate spellings that occur in the literature include: Mayátana, Mayátani, Mąwádanį, Mąwádąδį, Huatanis, Mandani, Wahtani, Mantannes, Mantons, Mendanne, Mandanne, Mandians, Maw-dân, Meandans, les Mandals, Me-too´-ta-häk, Numakshi, Rųwą́'kši, Wíhwatann, Mevatan, Mevataneo.

[15] Investigation of their sites on the northern Plains have revealed items traceable as well to the Tennessee River, Florida, the Gulf Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard.

Spanish merchants and officials in St. Louis (after France had ceded its territory west of the Mississippi River to Spain in 1763) explored the Missouri and strengthened relations with the Mandan (whom they called Mandanas).

[27] By 1804 when Lewis and Clark visited the tribe, the number of Mandan had been greatly reduced by smallpox epidemics and warring bands of Assiniboine, Lakota and Arikara.

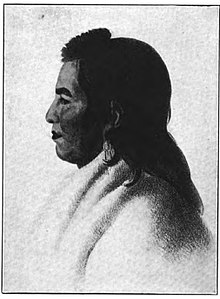

His skill at rendering so impressed Four Bears that he invited Catlin as the first man of European descent to be allowed to watch the sacred annual Okipa ceremony.

18th-century reports about characteristics of Mandan lodges, religion and occasional physical features among tribal members, such as blue and grey eyes along with lighter hair coloring, stirred speculation about the possibility of pre-Columbian European contact.

Catlin believed the Mandan were the "Welsh Indians" of folklore, descendants of Prince Madoc and his followers who had emigrated to America from Wales in about 1170.

[34] Archaeologist Ken Feder has stated that none of the material evidence that would be expected from a Viking presence in and travel through the American Midwest exists.

In the words of "Cheyenne warrior" and Lakota-allied George Bent: "... the Sioux moved to the Missouri and began raiding these two tribes, until at last the Mandans and Rees [Arikaras] hardly dared go into the plains to hunt buffalo".

Chief Four Bears reportedly said, while ailing, "a set of Black harted [sic] Dogs, they have deceived Me, them that I always considered as Brothers, has turned Out to be My Worst enemies".

Yet in light of all the deaths, the almost complete annihilation of the Mandans, and the terrible suffering the region endured, the label criminal negligence is benign, hardly befitting an action that had such horrendous consequences.

[47]Some scholars who have argued that the transmission of smallpox to Native Americans during the 1836-40 epidemic was intentional, including Ann F. Ramenofsky who asserted in 1987: "Variola Major can be transmitted through contaminated articles such as clothing or blankets.

[49] Some accounts repeat a story that an Indian sneaked aboard the St. Peter and stole a blanket from an infected passenger, thus starting the epidemic.

The many variations of this account have been criticized by both historians and contemporaries as fiction, a fabrication intended to assuage the guilt of white settlers for displacing the Indians.

With the creation of the Fort Berthold Reservation by Executive Order on April 12, 1870, the federal government acknowledged only that the Three Affiliated Tribes held 8 million acres (32,000 km2).

They drafted a constitution to elect representative government and formed the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes, known as the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation.

While New Town was constructed for the displaced tribal members, much damage was done to the social and economic foundations of the reservation by the loss of flooded areas.

[59] Reconstructions of these lodges may be seen at Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park near Mandan, North Dakota, and the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site.

[4] Clark noted that the Mandan obtained horses and leather tents from peoples to the west and southwest such as Crows, Cheyennes, Kiowas and Arapahos.

[4] Up until the late 19th century, when Mandan people began adopting Western-style dress, they commonly wore clothing made from the hides of buffalo, as well as of deer and sheep.

The long hair in the back would create a tail-like feature, as it would be gathered into braids then smeared with clay and spruce gum, and tied with cords of deerskin.

Then they were led to a hut, where they had to sit with smiling faces while the skin of their chest and shoulders was slit and wooden skewers were thrust behind the muscles.

After fainting, the warriors would be pulled down and the men (women were not allowed to attend this ceremony) would watch them until they awoke, proving the spirits' approval.

[64][failed verification] The version of the Okipa as practiced by the Lakota may be seen in the 1970 film A Man Called Horse starring Richard Harris.

The Mandan and the two culturally related tribes, the Hidatsa (Siouan) and Arikara (Caddoan), while being combined have intermarried but do maintain, as a whole, the varied traditions of their ancestors.

[66] The most recent addition to the New Town area has been the new Four Bears Bridge, which was built in a joint effort between the three tribes and the North Dakota Department of Transportation.