Real projective plane

, is a two-dimensional projective space, similar to the familiar Euclidean plane in many respects but without the concepts of distance, circles, angle measure, or parallelism.

The fundamental objects in the projective plane are points and straight lines, and as in Euclidean geometry, every pair of points determines a unique line passing through both, but unlike in the Euclidean case in projective geometry every pair of lines also determines a unique point at their intersection (in Euclidean geometry, parallel lines never intersect).

Topologically, the real projective plane is compact and non-orientable (one-sided).

The topological real projective plane can be constructed by taking the (single) edge of a Möbius strip and gluing it to itself in the correct direction, or by gluing the edge to a disk.

The projective plane cannot be embedded (that is without intersection) in three-dimensional Euclidean space.

The proof that the projective plane does not embed in three-dimensional Euclidean space goes like this: Assuming that it does embed, it would bound a compact region in three-dimensional Euclidean space by the generalized Jordan curve theorem.

This quotient space of the sphere is homeomorphic with the collection of all lines passing through the origin in R3.

[2] The projective plane can be immersed (local neighbourhoods of the source space do not have self-intersections) in 3-space.

[3] Steiner's Roman surface is a more degenerate map of the projective plane into 3-space, containing a cross-cap.

A polyhedral representation is the tetrahemihexahedron,[4] which has the same general form as Steiner's Roman surface, shown here.

Looking in the opposite direction, certain abstract regular polytopes – hemi-cube, hemi-dodecahedron, and hemi-icosahedron – can be constructed as regular figures in the projective plane; see also projective polyhedra.

A cross-capped disk has a plane of symmetry that passes through its line segment of double points.

A cross-capped disk can be sliced open along its plane of symmetry, while making sure not to cut along any of its double points.

Projecting the self-intersecting disk onto the plane of symmetry (z = 0 in the parametrization given earlier) which passes only through the double points, the result is an ordinary disk which repeats itself (doubles up on itself).

The points on the rim of the self-intersecting disk come in pairs which are reflections of each other with respect to the plane z = 0.

A cross-capped disk is formed by identifying these pairs of points, making them equivalent to each other.

Therefore, the surface shown in Figure 1 (cross-cap with disk) is topologically equivalent to the real projective plane RP2.

A projective line corresponding to the plane ax + by + cz = 0 in R3 has the homogeneous coordinates (a : b : c).

Thus, these coordinates have the equivalence relation (a : b : c) = (da : db : dc) for all nonzero values of d. Hence a different equation of the same line dax + dby + dcz = 0 gives the same homogeneous coordinates.

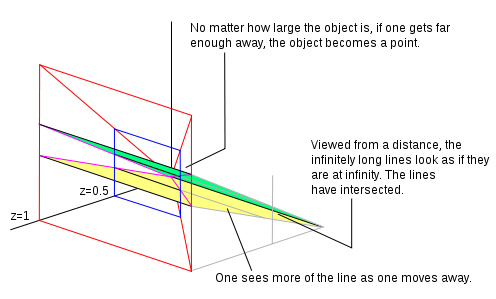

From where we are standing (given our visual capabilities) we can see only so much of the plane, which we represent as the area outlined in red in the diagram.

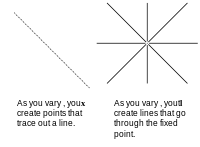

If we keep the coefficients constant and vary the points that satisfy the equation we create a line.

The cross product will find such a vector: the line joining two points has homogeneous coordinates given by the equation x1 × x2.

The real projective plane P2(R) is the quotient of the two-sphere by the antipodal relation (x, y, z) ~ (−x, −y, −z).

By gluing together projective planes successively we get non-orientable surfaces of higher demigenus.

The article on the fundamental polygon describes the higher non-orientable surfaces.