Marcelino Ulibarri Eguilaz

The Basque family of Ulibarri (spelled also Ullibarri, Ulíbarri or Uribarri)[1] was first recorded in the Medieval era; over the centuries it became very branched, also in America, and produced a number of recognized personalities.

[3] His son and Marcelino's grandfather, Juan Ciriaco de Ulibarri Mélida (died 1883),[4] was noted as "rico propietario" in Muez, a hamlet in the central Navarrese zone known as Tierra Estella.

[21] It is neither clear whether and if yes when and where he pursued an academic career, especially given very complex specialized, administrative, and bureaucratic tasks he would perform in the future; some press notes from his early 20s mention him in relation to Zaragoza[22] and some suggest a juridical background.

[27] At some stage, yet no later than in the early 1920s, he joined La Equitativa,[28] a Spanish subsidiary of the US insurance company, and worked in its Zaragoza branch, growing to mid-range management positions in the mid-1920s.

[40] During the Third Carlist War in the 1870s the family house in Muez hosted the claimant Carlos VII and his wife, who spent few nights there in wake of the Abárzuza battle; Marcelino's mother would later for decades keep recollecting this episode.

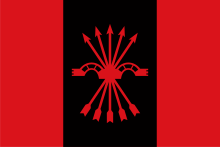

[41] First information on Marcelino's engagements are related to his early 20s; in 1904 he presided over a Carlist committee organizing a local Traditionalist event in Zaragoza,[42] and in 1905 he was within a group which set up Juventud Carlista in the Aragonese capital.

In 1910 he represented jefé regional, Pascual Comín, in the local Junta de Censo, apparently when protesting alleged electoral irregularities;[45] the same year he was among organizers[46] and major speakers[47] during rallies against secular schools, called by right-wing Catholic groupings.

[53] In 1918 he took part in a meeting organized by Diputación Provincial, inspired by Junta de la Defensa del Agricultor and intended to tackle agricultural problems; it is not clear what institution he represented.

During the decade Ulibarri was recorded mostly as taking part in various Catholic initiatives, e.g. in 1923 he co-organized a local Zaragoza campaign against blasphemy,[55] and in 1929 he was active in the male Christian brotherhood of Caballeros del Pilar;[56] both his family[57] and scholars claimed later that he has always been very religious.

Since the early months of the Second Republic Ulibarri took park in labors intended to unite local right-wing opposition; in December 1931 he was noted as co-signatory of a manifesto, which launched Unión de Derechas; this provincial Zaragoza alliance was supposed to group the Carlists from Comunión Tradicionalista and politicians from Acción Nacional.

[75] Ulibarri was involved in conspiracy talks leading to Carlist taking part in the July Coup; the national leader Manuel Fal Conde counted him among the faction who did not believe in a standalone insurrection, but who advocated a joint Carlist-military action instead.

During the meeting Ulibarri tried to arrange Fal's return to Nationalist zone, though he also criticised Junta Nacional Carlista de Guerra, the central Carlist wartime executive, for not having co-ordinated its initiatives with the military.

However, Rodezno responded that too many Navarros in Junta Política would not make a good impression, and eventually Ulibarri was replaced by Carlists from La Rioja and from Madrid.

[98] Some authors claim that it was Ulibarri who “planted in the mind of his powerful friend” (i.e. Franco) the idea of creating an investigative body, which materialized as OIPA,[99] and some even maintain that he was heading the Office,[100] but other scholars do not mention him as related.

[111] Many scholars discuss Ulibarri's nomination against the background of his alleged friendship with Franco, reportedly dating back to the 1928–1931 years in Zaragoza, and their common anti-masonic obsession.

[112] Others prefer rather to underline his close familiarity with Serrano Suñer, who has just emerged as Franco's key advisor and architect of the new regime; reportedly he was responsible for Ulibarri's nomination.

[115] None of the sources consulted discusses Ulibarri's record in La Equitativa, which has provided him with experience and competence in terms of investigation, document circulation and database management.

[118] As the Nationalist offensive in the northern enclave progressed,[119] in August Ulibarri and his men travelled to freshly seized Santander to comb out Republican documentation left behind.

[121] In April 1938 the provisional ministry of interior, headed by Serrano Suñer, issued a decree which established Delegación del Estado para Recuperación de Documentos (DERD).

[122] Affiliated to Ministerio de la Gobernación[123] though partially supervised by the military,[124] it was to recover, collect, catalogue and store all official documents produced by the Republicans, not only these related to freemasonry or Communist propaganda.

[142] Throughout the process he was frequently involved in conflict with other services, e.g. the Falange intelligence unit, DGS,[143] and SIPM,[144] apart from clashes with Juan Tusquets, who was reluctant to hand over documentation he had earlier collected.

[150] He also recommended that DERD engages in education – which in few years produced opening of an internal Museo de la Masonería[151] - and restructuring the institution, with one of its sections assuming a juridical role.

[163] Like in case of other institutions, scholars speculate that the appointment might have been related to Ulibarri's friendship either with Franco or with Serrano and his zealous anti-masonic and anti-Communist views, apart from his successful record in DERD.

In case of the former he turned to academic experts in penal law like Isaías Sánchez Tejerina from the University of Salamanca, asking them for advice as to legal framework of the persecution.

He underlined that "excesiva preocupación legalista" should be avoided; he also opted for non-public proceedings performed in absence of the person investigated and with no assistance on part of professionals in law.

Having resigned his positions in DERD and TERMC Ulibarri had no real power, be it in political or other terms, even though the press reported him as engaged in various legislative works[186] and some sources suggest some influence on personal appointments in Francoist administration, e.g. in 1940–1941 in Valencia.

[189] He terminated any links to mainstream Carlism, either on the regional Navarrese[190] or the national level,[191] and though featuring among best-known so-called carlo-franquistas, he also counted among “conocidos disidentes tradicionalistas”.

[192] In his final years in the late 1940s and early 1950s and reportedly for health reasons he withdrew to privacy; his death was noted in the press with moderate[193] and not necessarily accurate[194] acknowledgements.

Until the mid-1930s and during most of his lifetime Ulibarri remained a private figure, apart from local Navarrese and Aragonese Carlist circles mentioned only in societé column of Pamplona and Zaragoza newspapers.

There are two works, both PhD dissertations, where he was paid more attention: the one on DERD archive mentioned him 118 times[209] and in the one on anti-masonic measures against females he was dedicated a separate sub-chapter.