Juan Granell Pascual

In 1945-1953 he managed the state-run energy conglomerate ENDESA and was responsible for construction of the first coal-fired thermal power plant in Spain; he was also in executive bodies of numerous other companies.

[1] In the course of the centuries it got very branched and popular along all the Spanish Mediterranean coast and numerous individuals rose to publicly recognizable figures, but none of them has been identified as related to Granell Pascual.

[5] His social status is unclear and none of the sources consulted provides information what he was doing for a living, though some suggest that the family owned a large "finca citrícola" on the right bank of the Mijares river and were growing lemons and oranges.

Juan María,[24] Jesús[25] and Ignacio[26] worked as civil engineers, mostly in construction business; some held also teaching positions,[27] while Javier became the head surgeon in the public Madrid health service.

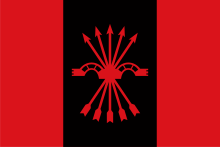

[30] Some data suggest that his father might have been related to Integrism[31] and that he remained a militant Catholic;[32] later propaganda prints claimed that Granell Pascual inherited the Traditionalist outlook, possibly highly flavored with Carlism, from his forefathers.

[33] There is no information on his political engagements prior to late 1931, when Granell Pascual was listed among the Madrid Integrists who paid homage to the defunct Carlist king, Don Jaime.

[37] During the 1933 electoral campaign to the Cortes the Castellón Carlists, led by Jaime Chicharro and Juan Bautista Soler, closed an alliance agreement with other right-wing organisations; Granell was included on the joint provincial list of candidates of Unión de Derechas.

He campaigned focused on religious issues and protested alleged anti-Catholic governmental policy;[38] following some controversies related to a rival lerrouxista counter-candidate eventually Comisión de Actas declared him elected.

[44] Granell did not feature prominently in the national Carlist organization; his only central role identified is membership in Tesoro de la Tradición, a financial branch of the executive.

[47] He remained engaged in regular local activities, like opening new círculos[48] or speaking at rallies, e.g. in Castellón[49] during so-called Gran Semana Tradicionalista,[50] in Onteniente[51] or Benicarló.

Exact mechanism of his elevation is unclear; some authors speculate that it might have been related to the Jesuit influence, his own anti-masonic zeal and connections to pro-Franco collaborative faction within Carlism.

[64] As civil governor Granell abandoned any Carlist sentiments he might have still nurtured and adopted a vehement, militant Falangist stand, pursued in terms of propaganda arrangements and personal appointments.

[65] He found himself at odds with the Bilbao mayor and provincial Biscay FET leader, another Carlist José María Oriol, who attempted to cultivate moderate Traditionalist policy.

[71] In July 1941 Granell was released as civil governor and moved to central administration; he assumed the post of Subsecretario de industria in the Ministry of Industry and Commerce.

[92] Some authors claim that Granell “se retiró de la política para atender a sus negocios”,[93] but there is no evidence that he was running his own private business.

[104] Resident in Madrid,[105] he became the unofficial Burriana representative in the capital[106] and was credited for numerous local investments, be it the road and railway infrastructure development, water delivery and drainage system upgrades, refurbishment and enhancement of Guardia Civil offices, extension of piers and construction of new buildings in the harbor,[107] saving local college from closure[108] and especially reconstruction of the iconic El Salvador church bell-tower, blown up by retreating Republican troops.