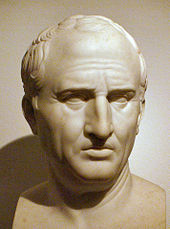

Marcus Marius Gratidianus

Although this period of Roman history is marked by the extreme violence and cruelty practiced by partisans on each side, Gratidianus suffered a particularly vicious death during Sulla's proscription; in the most sensational accounts, he was tortured and dismembered by Catiline at the tomb of Quintus Lutatius Catulus, in a manner that evoked human sacrifice, and his severed head was carried through the streets of Rome on a pike.

He may also have had a particularly pungent relationship with his brother-in-law; there is reason to believe that his sister, Gratidia, was the first wife of Lucius Sergius Catilina, or "Catiline", who was later accused by Cicero of Gratidianus' torture and murder.

[5] In 92 BC, Antonius deployed his famed oratorical skills in defending his friend's son when Gratidianus was sued by the oyster-breeder and real-estate speculator Sergius Orata in a civil case involving the sale of a property on the Lucrine Lake.

A number of praetors and tribunes drafted a currency reform measure to reassert the former official exchange rate of silver (the denarius) and the bronze as, which had been allowed to fluctuate and destabilize.

The currency measure pleased the equites, or business class, more than did the debt reform legislation of Lucius Valerius Flaccus, which had permitted the repayment of loans at one-quarter of the amount owed,[15] and it was enormously popular with the plebs.

The two reforms are not incompatible,[17] but historian and numismatist Michael Crawford finds no widespread evidence of silver-plated or counterfeit denarii in surviving coin hoards from the period leading up to the edict.

Since the measures taken by Gratidianus cannot be shown to address a problem of counterfeit money, the edict is best understood as part of the Cinnan government's efforts to restore and create a perception of stability in the wake of the civil war.

The sources express no surprise or disapproval toward tending cult for a living man, which may have been a tradition otherwise little evidenced; the theological basis of the homage paid to Gratidianus is unclear.

[22] Seneca, following Cicero's lead, criticizes Gratidianus for compromising his integrity in claiming credit for the legislation, by which he had hoped to garner support for his candidacy as consul.

[24] Gratidianus had an unusual second praetorship, possibly as a "consolation prize" granted him when the Cinnans decided to back the younger Marius and Gnaeus Papirius Carbo for the consulship of 82.

[28] The orator claimed that Catiline cut off Gratidianus' head, and carried it through the city from the Janiculum to the Temple of Apollo, where he delivered it to Sulla "full of soul and breath".

Despite the strength and persistence of the tradition that Catiline took the lead role in the execution, the more logical instigator would have been Catulus' son, exhibiting pietas towards his father by seeking revenge as an alternative to justice.

[36] The site of the family tomb, otherwise unknown, is mentioned only in connection with this incident and identified vaguely as "across the Tiber",[37] which accords with Cicero's statement that the head was carried from the Janiculum to the Temple of Apollo.

Human sacrifices at Rome were rare, but documented in historical times — "their savagery was closely connected with religion"[41] — and had been banned by law only fifteen years before the death of Gratidianus.

[42] The relative "lateness" of specifying the tomb of Catulus as the site also depends on the dating of one of the other sources on the killing, the Commentariolum petitionis, an epistolary pamphlet traditionally attributed to Cicero's brother, Quintus, but suspected of being an exercise in prosopopoeia by another writer in Imperial times.

Seneca, though closely echoing Sallust's wording, names Catiline, adds to the list of mutilations the cutting out of Gratidianus' tongue, and places the killing at the tomb of Catulus, explicitly linking the favor of the people to the extreme measures taken at his death: The people had dedicated statues to Marcus Marius throughout the neighborhoods and offered devotions with frankincense and wine; Lucius Sulla gave the order for his legs to be broken, his eyes gouged out, his tongue and his hands cut off and — as if he could die as many times as he was wounded — systematically carved up his body inch by inch.

[48]Lucan, Seneca's nephew and like him writing under the Imperial terror of Nero, who drove them both to suicide, has the most extensive list of tortures in his epic poem on the civil war of the 40s.

Lucan places his account in the mouth of an old man who had lived through Sulla's civil war four decades before the time narrated in the poem, and like the earlier sources emphasizes that the Roman people were witnesses to the act.

[52] On the anniversary of Caesar's death in 40 BC, after achieving a victory at the siege of Perugia, the future Augustus executed 300 senators and knights who had fought against him under Lucius Antonius.

[53] Both Suetonius[54] and Cassius Dio[55] characterize the slaughter as a sacrifice, noting that it occurred on the Ides of March at the altar to the divus Julius, the victor's newly deified adoptive father.

Orosius, whose primary source for the Republic was the lost portions of Livy's history,[59] provides the peculiar detail that Gratidianus was held in a goat-pen before he was bound and exhibited.