Mark Oliphant

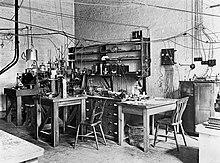

He was awarded an 1851 Exhibition Scholarship in 1927 on the strength of the research he had done on mercury, and went to England, where he studied under Sir Ernest Rutherford at the University of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory.

Oliphant also formed part of the MAUD Committee, which reported in July 1941, that an atomic bomb was not only feasible, but might be produced as early as 1943.

After the war, Oliphant returned to Australia as the first director of the Research School of Physical Sciences and Engineering at the new Australian National University (ANU), where he initiated the design and construction of the world's largest (500 megajoule) homopolar generator.

His father was Harold George "Baron" Olifent,[1] a civil servant with the South Australian Engineering and Water Supply Department and part-time lecturer in economics with the Workers' Educational Association.

[18] In 1925, Oliphant heard a speech given by the New Zealand physicist Sir Ernest Rutherford, and he decided he wanted to work for him – an ambition that he fulfilled by earning a position at the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge in 1927.

He soon met other researchers at the Cavendish Laboratory, including Patrick Blackett, Edward Bullard, James Chadwick, John Cockcroft, Charles Ellis, Peter Kapitza, Egon Bretscher, Philip Moon and Ernest Walton.

[22] Oliphant submitted his PhD thesis on The Neutralization of Positive Ions at Metal Surfaces, and the Emission of Secondary Electrons in December 1929.

In 1933, Blackett discovered tracks in his cloud chamber that confirmed the existence of the positron and revealed the opposing spiral traces of positron–electron pair production.

When Chadwick left the Cavendish Laboratory for the University of Liverpool in 1935, Oliphant and Ellis both replaced him as Rutherford's assistant director for research.

[23] Samuel Walter Johnson Smith's imminent mandatory retirement at age 65 prompted a search for a new Poynting Professor of Physics at the University of Birmingham.

[41] The university wanted not just a replacement, but a well-known name, and was willing to spend lavishly in order to build up nuclear physics expertise at Birmingham.

The Fall of Singapore in February 1942 led him to offer his services to John Madsen, the Professor of Electrical Engineering at the University of Sydney, and the head of the Radiophysics Laboratory at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, which was responsible for developing radar.

[51] At the University of Birmingham in March 1940, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls examined the theoretical issues involved in developing, producing and using atomic bombs in a paper that became known as the Frisch–Peierls memorandum.

They considered what would happen to a sphere of pure uranium-235, and found that not only could a chain reaction occur, but it might require as little as 1 kilogram (2 lb) of uranium-235 to unleash the energy of hundreds of tons of TNT.

The first person they showed their paper to was Oliphant, and he immediately took it to Sir Henry Tizard, the chairman of the Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Warfare (CSSAW).

I called on Briggs in Washington [DC], only to find out that this inarticulate and unimpressive man had put the reports in his safe and had not shown them to members of his committee.

Chadwick was adamant that the cooperation with the Americans should continue, and that Oliphant and his team should remain until the task of building an atomic bomb was finished.

[70] In April 1946, the Prime Minister, Ben Chifley, asked Oliphant if he would be a technical advisor to the Australian delegation to the newly formed United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC), which was debating international control of nuclear weapons.

Oliphant agreed, and joined the Minister for External Affairs, H. V. Evatt and the Australian Representative at the United Nations, Paul Hasluck, to hear the Baruch Plan.

[71] Chifley and the Secretary for Post-War Reconstruction, Dr H. C. "Nugget" Coombs, also discussed with Oliphant a plan to create a new research institute that would attract the world's best scholars to Australia and lift the standard of university education nationwide.

But Oliphant accepted, and in 1950 returned to Australia as the first Director of the Research School of Physical Sciences and Engineering at the Australian National University.

Locating the new research institute in Canberra would place it close to the Snowy Mountains Scheme, which was planned to be the centrepiece of a new nuclear power industry.

Arrangements were made for Australian scientists to be seconded to the British Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell, but the close cooperation he sought was stymied by security concerns arising from Britain's commitments to the United States.

[78] A threat to the future of the university arose in the wake of the 1949 election, when the Liberal Party of Australia led by Robert Menzies won.

Menzies defended it, but in 1954 he announced that it had entered a period of consolidation, with a funding ceiling, ending the possibility of successful competition with universities in Europe and North America.

[23] Oliphant founded the Australian Academy of Science in 1954, teaming up with David Martyn to overcome the obstacles that had frustrated previous attempts.

During this period, he caused great concern to Dunstan when he strongly supported the decision of the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, in the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis.

[85] Oliphant had secretly written, "[t]here is something inherent in the personality of the Aborigine which makes it difficult for him to adapt fully to the ways of the white man."

The authors of Oliphant's biography noted that "that was the prevailing attitude of almost the entire white population of Australia until well after World War II".

[5] His daughter-in-law, Monica Oliphant, is a distinguished Australian physicist specialising in the field of renewable energy, for which she was made an Officer of the Order of Australia in 2015.