Maria Rundell

In addition to dealing with food preparation, it offers advice on medical remedies and how to set up a home brewery and includes a section entitled "Directions to Servants".

In 1819 Rundell asked Murray to stop publishing Domestic Cookery, as she was increasingly unhappy with the way the work had declined with each subsequent edition.

A court case ensued, and legal wrangling between the two sides continued until 1823, when Rundell accepted Murray's offer of £2,100 for the rights to the work.

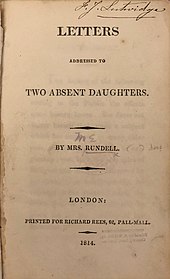

The work contains the advice a mother would give to her daughters on subjects such as death, friendship, how to behave in polite company and the types of books a well-mannered young woman should read.

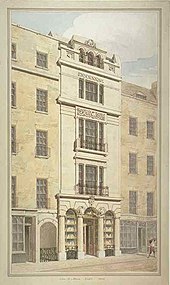

[4] The document Rundell gave Murray was nearly ready for publication; he added a title page, the frontispiece and an index, and had the collection edited.

Rundell wanted no payment for the book, as in some social circles the receipt of royalties was thought improper,[10] and the first edition contained a note from the publishers that read: the directions which follow were intended for the conduct of the families of the authoress's own daughters, and for the good arrangement of their table, so as to unite a good figure with proper economy ...

[19] The unnamed male reviewer for The Monthly Repertory of English Literature wrote "we can only report that certain of our female friends (better critics on this subject than ourselves) speak favourably of the work".

[26] She complained of one editor "He has made some dreadful blunders, such as directing rice pudding seeds to be kept in a keg of lime water, which latter was mentioned to preserve eggs in."

[42] Her introduction opens: The mistress of a family should always remember that the welfare and good management of the house depend on the eye of the superior; and consequently that nothing is too trifling for her notice, whereby waste may be avoided; and this attention is of more importance now that the price of every necessary of life is increased to an enormous degree.

[43]The book contains recipes for fish, meat, pies, soups, pickles, vegetables, pastry, puddings, fruits, cakes, eggs, cheese and dairy.

[2] The food writer Alan Davidson holds that Domestic Cookery does not have many innovative features, although it does have an early recipe for tomato sauce.

[14] Additions included medical remedies and advice; the journalist Elizabeth Grice notes that these, "if efficacious, could spare women the embarrassment of submitting to a male doctor".

[53] The advice included how to behave in polite company, the types of books a well-mannered young woman should read, and how to write letters.

[54][55] As it was normal at the time for girls and young women to have no formal education, it was common and traditional for mothers to provide such advice.

[60] In 1861, Isabella's husband, Samuel, published Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, which also contained several of Rundell's recipes.

[61][k] Domestic Cookery was also heavily plagiarised in America,[58] with Rundell's recipes being reproduced in Mary Randolph's 1824 work The Virginia House-Wife and Elizabeth Ellicott Lea's A Quaker Woman's Cookbook.

[66] Rundell is quoted around twenty times in the Oxford English Dictionary,[67] including for the terms "apple marmalade",[68] "Eve's pudding",[69] "marble veal"[70] and "neat's tongue".

[4] For Grice, "Compared with the illustrious Eliza Acton—who could write better—and the ubiquitous Mrs Beeton—who died young—Mrs Rundell has unfairly slipped from view.

The 20th-century cookery writer Elizabeth David references Rundell in her articles, collected in Is There a Nutmeg in the House,[72] which includes her recipe for "burnt cream" (crème brûlée).

[73] In English Bread and Yeast Cookery (1977), she includes Rundell's recipes for muffins, Lancashire pikelets (crumpets), "potato rolls", Sally Lunns, and black bun.