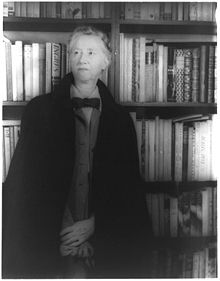

Marianne Moore

[1] Moore was born in Kirkwood, Missouri, in the manse of the Presbyterian church where her maternal grandfather, John Riddle Warner, served as pastor.

The family wrote voluminous letters to one another throughout their lives, often addressing each other by playful nicknames based on characters from The Wind in the Willows and using a private language.

[4] After her grandfather died in 1894, the three stayed with relatives near Pittsburgh for two years, then moved to Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where her mother found employment teaching English in a private girls school.

At Bryn Mawr, Moore started writing short stories and poems for Tipyn O'Bob,[6] the campus literary magazine, and decided to become a writer.

After graduation, she worked briefly at Melvil Dewey's Lake Placid Club,[7] then taught business subjects at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School from 1911 to 1914.

This position in the literary and arts community extended her influence as an arbiter of modernist taste; much later, she encouraged promising young poets, including Elizabeth Bishop, Allen Ginsberg, John Ashbery, and James Merrill.

When The Dial ceased publication in 1929, she moved to 260 Cumberland Street[11] in the Fort Greene neighborhood of Brooklyn, where she remained for thirty-six years.

In the book's introduction, T. S. Eliot wrote, "My conviction has remained unchanged for the last 14 years that Miss Moore's poems form part of the small body of durable poetry written in our time.

"[4] After years of seclusion, she emerged as a celebrity, speaking at college campuses across the country and appearing in photographic essays in Life and Look magazines.

[23] In 1955, Moore was invited informally by David Wallace, manager of marketing research for Ford's "E-car" project, and his co-worker Bob Young, to suggest a name for the car.

[25] Her entire library, knick-knacks (including a baseball signed by Mickey Mantle), all of her correspondence, photographs, and poetry drafts are available for public viewing.

As Moore wrote, as a one-line epigraph to Complete Poems, which offered her well-known work "Poetry" cut down from twenty-nine lines to three: "Omissions are not accidents.

[29] In her will, she established a fund for the support of the Camperdown Elm in Brooklyn's Prospect Park, a rare and ancient tree that she had celebrated in a poem.

[3] Later in her Selected Poems of 1969, she also commented in regard to her poetic form, that "in anything I have written, there have been lines in which the chief interest is borrowed, and I have not yet been able to outgrow this hybrid method of composition".

One must make a distinction however: when dragged into prominence by half poets, the result is not poetry Moore translated the seventeenth-century Fables of La Fontaine into English.

Notably, Moore wrote in her personal letters to her family that she attended lectures at Bryn Mawr by the well-known feminist Jane Addams and the British suffragette Anne Cobden-Sanderson.

"[40] Moore visited New York City in 1909 with another Bryn Mawr student, where she heard a lecture by the Colorado suffragist Judge Ben Lindsey, went to a suffrage mass meeting, and saw J. M. Barrie's classic suffragist-themed play What Every Woman Knows.

[39] There is speculation that Moore also participated in the women's suffrage parade of 1913 in Washington, D.C., one day before Woodrow Wilson's presidential inauguration.

[17] Moore was never as public about her involvement in the suffrage movement after that parade in 1913, because afterward she began participating anonymously, mostly through writing, using a pseudonym.

Dr. Mary Chapman (University of British Columbia) argues that Moore was the writer of suffragist writings of the time in Carlisle news publications and that could be analyzed by examining her specific writing style alongside suffragist prose and poetry that were published in the Carlisle Evening Herald in 1915: "Many of the prosuffrage articles that appeared in the Herald exhibit Moore's characteristic reliance on quotation.

", which scholars believe could stand for Marianne Moore because "the absence of any other documented unmarried female suffragists in the Carlisle area with the initials M.M.