Marine geology

Marine geological studies were of extreme importance in providing the critical evidence for sea floor spreading and plate tectonics in the years following World War II.

The deep ocean floor is the last essentially unexplored frontier and detailed mapping in support of economic (petroleum and metal mining), natural disaster mitigation, and academic objectives.

[1][2] HMS Challenger hosted nearly 250 people, including sailors, engineers, carpenters, marines, officers, and a 6-person team of scientists, led by Charles Wyville Thomson.

After ships were equipped with sonar sensors, they travelled back and forth across the Atlantic Ocean collecting observations of the sea floor.

[6] In 1953, the cartographer Marie Tharp generated the first three-dimensional relief map of the ocean floor which proved there was an underwater mountain range in the middle of the Atlantic, along with the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

[6] With support from the maps of the sea floor, and the recently developed theory of plate tectonics and continental drift, Hess was able to prove that the Earth's mantle continuously released molten rock from the mid-ocean ridge and that the molten rock then solidified, causing the boundary between the two tectonic plates to diverge.

[10] There are multiple methods for collecting data from the sea floor without physically dispatching humans or machines to the bottom of the ocean.

[12] The side-scan sonar is useful for scientists as it is a quick and efficient way of collecting imagery of the sea floor, but it cannot measure other factors, such as depth.

[11] Similarly to side-scan sonar, multibeam bathymetry uses a transducer array to send and receive sound waves in order to detect objects located on the sea floor.

[13] Unlike side-scan sonar, scientists are able to determine multiple types of measurements from the recordings and make hypothesis' on the data collected.

The importance of objects in the water column to marine geology is identifying specific features as bubble plumes can indicate the presence of hydrothermal vents and cold seeps.

[14] Mounted to the hull of a ship, the system releases low-frequency pulses which penetrate the surface of the sea floor and are reflected by sediments in the sub-surface.

Some sensors can reach over 1000 meters below the surface of the sea floor, giving hydrographers a detailed view of the marine geological environment.

[2] Many sub-bottom profilers can emit multiple frequencies of sound to record data on a multitude of sediments and objects on and below the sea floor.

When accompanied with geophysical data from multibeam sonar and physical data from rock and core samples, the sub-bottom profiles delivers insights on the location and morphology of submarine landslide, identifies how oceanic gasses travel through the subsurface, discover artifacts from cultural heritages, understand sediment deposition, and more.

[22] The benefit to a magnetometer compared to sonar devices is its ability to detect artifacts and geological features on top and underneath the seafloor.

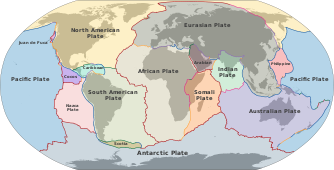

Plate tectonics is a scientific theory developed in the 1960s that explains major land form events, such as mountain building, volcanoes, earthquakes, and mid-ocean ridge systems.

[26] The idea is that Earth's most outer layer, known as the lithosphere, that is made up of the crust and mantle is divided into extensive plates of rock.

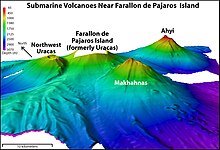

[8] In regards to marine geology, the movement of the plates explains seafloor spreading and mid-ocean ridge systems, subduction zones and trenches, volcanism and hydrothermal vents, and more.

[47][48] These vents emit large volumes of super-heated, metal infused fluids that rise and rapidly cool when mixed with the cold seawater.

The chemical reaction causes sulfur and minerals to precipitate and from chimneys, towers, and mineral-rich deposits on the sea floor.

[50] They are typically found unattached, spread across the abyssal seafloor and contain metals crucial for building batteries and touch screens, including cobalt, nickel, copper, and manganese.

[57] Underwater geological features can dictate ocean properties, such as currents and temperatures, which are crucial for location placement of the necessary infrastructure to produce energy.

[61] Analyzing the effects that the seafloor has on water movement can help support planning and location selection of generators offshore and optimize energy farming.

With global events causing potentially irreversible damage to the sea habitats, such as deep-sea mining and bottom trawling, marine geology can help us study and mitigate the effects of these activity.

[66] During this process, the net damages the seafloor by scraping and removing animals and vegetation living on the seabed, including coral reefs, sharks, and sea turtles.

[73] Marine geology supports the study of sediment types, current patterns, and ocean topography to predict erosional trends which can protect these environments.

[76][77] Marine geology and understanding plate boundaries supports the development of early warning systems and other mitigation techniques to protect the people and environments who may be susceptible to natural disasters.

The Okeanos Explorer, a vessel owned by NOAA, has already mapped over 2 million km2 of the seafloor using multibeam sonar since 2008, but this technique has proved to be too time-consuming.

Because of this, an international collaboration effort to create a high-definition map of the entire seafloor was developed, called the Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project.