Mariner 4

Launched on November 28, 1964,[2] Mariner 4 performed the first successful flyby of the planet Mars, returning the first close-up pictures of the Martian surface.

Initially expected to remain in space for eight months, Mariner 4's mission lasted about three years in solar orbit.

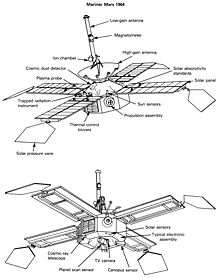

The octagonal frame housed the electronic equipment, cabling, midcourse propulsion system, and attitude control gas supplies and regulators.

Monopropellant hydrazine was used for propulsion, via a four-jet vane vector control motor, with 222-newton (50 lbf) thrust, installed on one of the sides of the octagonal structure.

The space probe's attitude control was provided by 12 cold nitrogen gas jets mounted on the ends of the solar panels and three gyros.

[10] The telecommunications equipment on Mariner 4 consisted of dual S-band transmitters (with either a seven-watt triode cavity amplifier or a ten watt traveling-wave tube amplifier) and a single radio receiver which together could send and receive data via the low- and high-gain antennas at 8⅓ or 33⅓ bits per second.

The central computer and sequencer operated stored time-sequence commands using a 38.4 kHz synchronization frequency as a time reference.

Temperature control was achieved through the use of adjustable louvers mounted on six of the electronics assemblies, plus multilayer insulating blankets, polished aluminum shields, and surface treatments.

Other measurements that could be made included: Mariner 4 was also supposed to carry an ultraviolet photometer on the left side of the aft TV Camera scan platform.

Late in testing, it was discovered that the inclusion of the UV photometer produced electrical problems that would have jeopardized the TV Camera.

[11] After Mariner 3 was a total loss due to failure of the payload shroud to jettison, JPL engineers suggested that there had been a malfunction caused during separation of the metal fairing exterior from the fiberglass inner lining due to pressure differences between the inner and outer part of the shroud and that this could have caused the spring-loaded separation mechanism to become tangled and fail to detach properly.

[3][10] A consistent problem that plagued the spacecraft during the early portion of its mission was that roll error signal transients would occur frequently and on occasion would cause loss of the Canopus star lock.

After a study of the problem, the investigators concluded that the behavior was due to small dust particles that were being released from the spacecraft by some means and were drifting through the star sensor field-of-view.

[6] On January 5, 1965, 36 days after launch and 10,261,173 km (6,375,997 mi) from Earth, Mariner 4 reduced its rate of transmission of scientific data from 33 1/3 to 8 1/2 bits per second.

The images covered a discontinuous swath of Mars starting near 40° N, 170° E, down to about 35° S, 200° E, and then across to the terminator at 50° S, 255° E, representing about 1% of the planet's surface.

Transmission of the taped images to Earth began about 8.5 hours after signal reacquisition and continued until August 3.

[16] The spacecraft performed all programmed activities successfully and returned useful data from launch until 22:05:07 UTC on October 1, 1965, when the long distance to Earth (309.2 million kilometres (192.1 million miles)) and the imprecise antenna orientation led to a temporary loss of communication with the spacecraft until 1967.

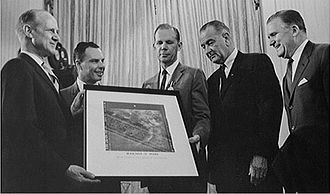

While waiting for the image data to be computer processed, the team used a pastel set from an art supply store to hand-color (paint-by-numbers style) a numerical printout of the raw pixels.

The cosmic dust detector registered 17 hits in a 15-minute span on September 15, part of an apparent micrometeoroid shower that temporarily changed the spacecraft attitude and probably slightly damaged its thermal shield.

[2] In addition, the plasma probe had its performance degraded by a resistor failure on December 8, 1964, but experimenters were able to recalibrate the instrument and still interpret the data.

[27] Images of craters and measurements of a thin atmosphere[23][28]—much thinner than expected[16]—indicating a relatively inactive planet exposed to the harshness of space, generally dissipated hopes of finding intelligent life on Mars.