Maritime Silk Road

[2] The Maritime Silk Road was primarily established and operated by Austronesian sailors in Southeast Asia who sailed large long-distance ocean-going sewn-plank and lashed-lug trade ships.

This network later included parts of Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and other areas in Southeast Asia where these jade ornaments, along with other trade goods, were exchanged (also known as the Sa Huynh-Kalanay Interaction Sphere).

[15][16][11][12] These early contacts resulted in the introduction of Austronesian crops and material culture to South Asia,[16] including betel nut chewing, coconuts, sandalwood, domesticated bananas,[16][15] sugarcane,[17] cloves, and nutmeg.

Both sites are coastal settlements and part of the jade trade network, indicating that the maritime routes of Austronesians had already reached South Asia by this period.

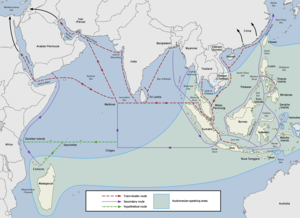

These linked Sri Lanka, the Malabar Coast of India, Persia, Mesopotamia, Arabia, Egypt, the Horn of Africa, and the Greco-Roman civilizations in the Mediterranean.

[1][13] Austronesian thalassocracies controlled the flow of trade in the eastern regions of the Maritime Silk Road, especially the polities around the straits of Malacca and Bangka, the Malay Peninsula, and the Mekong Delta; through which passed the main routes of the Austronesian trade ships to Giao Chỉ (in the Tonkin Gulf) and Guangzhou (southern China), the endpoints (later also including Quanzhou by the 10th century CE).

[14] The main route of the western regions of the Maritime Silk Road directly crosses the Indian Ocean from the northern tip of Sumatra (or through the Sunda Strait) to Sri Lanka, southern India and Bangladesh, and the Maldives.

Secondary routes also pass through the coastlines of the Bay of Bengal, the Arabian Sea, and southwards along the coast of East Africa to Zanzibar, the Comoros, Madagascar, and the Seychelles.

Books written by Chinese monks like Wan Chen and Hui-Lin contain detailed accounts of the large trading vessels from Southeast Asia dating back to at least the 3rd century CE.

[28] Records from Portuguese explorers in the late 15th and early 16th centuries indicate that direct maritime links between Indonesia and Madagascar persisted up until shortly before the colonial period.

[3][30] The Butuan boat burials of the Philippines, which feature eleven lashed-lug boat remains of the Austronesian boatbuilding traditions (individually dated from 689 CE to 988 CE), were found in association with large amounts of trade goods from China, Cambodia, Thailand (Haripunjaya and Satingpra), Vietnam, and as far as Persia, indicating they traded as far as the Middle East.

[34][4] The Song started sending trading expeditions to the region they referred to as Nan hai (Chinese: 南海; pinyin: Nánhǎi; lit.

This led to the establishment of new trading ports in Southeast Asia (like in Java and Sumatra) that specifically catered to the Chinese demand for goods like "dragon's brain perfume" (camphor) and other exotica.

Hayam Wuruk of Majapahit, angry at the actions of the vassal state, sent a punitive naval attack on Palembang in 1377, causing a diaspora of princes and nobles to the Kingdom of Singapura.

Parameswara, originally from Palembang and the last ruler of Singapura, fled to the western coast of the Malay Peninsula and founded the Muslim Sultanate of Malacca in the early 15th century.

Although ultimately, Zheng He's expeditions were successful in their goal of restoring trade relations with Southeast Asia (in this case, Malacca) and the Ming dynasty.

Shipbuilding of the formerly dominant Southeast Asian trading ships (jong, the source of the English term "junk") declined until it ceased entirely by the 17th century.

[3][41][4] There was new demand for spices from Southeast Asia and textiles from India and China, but these were now linked with direct trade routes to the European market, instead of passing through regional ports.

[3] The archaeological evidence of the Maritime Silk Road include numerous shipwrecks recovered along the route carrying (or associated with) trade goods sourced from various far-flung ports.

The origins of these early ships are readily identifiable by a combination of distinctive features and shipbuilding techniques used (such as lashed-lug and sewn boat traditions).

[3]: 12 [44][45][46][34] Almost all of the ships recovered from Southeast Asia before the 10th century belong to the Austronesian shipbuilding traditions, displaying variations and combinations of sewn-plank and lashed-lug techniques.

[42] China did not start building sea-going ships that ventured into the Maritime Silk Road until the Song dynasty (c. 10th century CE).

[4] By around the end of the Maritime Silk Road in the 14th and 15th century, ships that combined features of both Chinese and Austronesian boatbuilding traditions also start to appear, even reaching as far as India.

[34][42] Indian ships are similarly absent in the archaeological context in the eastern routes of the Maritime Silk Road prior to the 10th century CE.

[42] The archaeological evidence demonstrates that the trading ships in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean were Austronesian sewn-plank and lashed-lug vessels and Arab dhows prior to the 10th century CE.

[3]: 10 [41] Chinese ceramics are also valuable archaeological markers of the Maritime Silk Road due to their relative indestructibility and the fact that they can be precisely dated.

Traders on the maritime route faced different perils like weather and piracy, but they were not affected by political instability and could simply avoid areas in conflict.

[6] In May 2017, experts from various fields have held a meeting in London to discuss the proposal to nominate "Maritime Silk Route" as a new UNESCO World Heritage Site.

[3] India has also mythologized the Maritime Silk Road with Project Mausam, launched in 2014, which similarly attempts to reconnect old trade links with surrounding countries in the Indian Ocean.