Marketplace

[1] In different parts of the world, a marketplace may be described as a souk (from Arabic), bazaar (from Persian), a fixed mercado (Spanish), itinerant tianguis (Mexico), or palengke (Philippines).

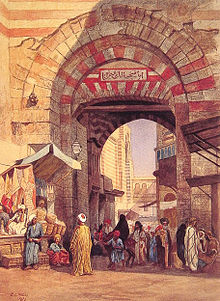

Middle Eastern bazaars were typically long strips with stalls on either side and a covered roof designed to protect traders and purchasers from the fierce sun.

Throughout the medieval period, increased regulation of marketplace practices, especially weights and measures, gave consumers confidence in the quality of market goods and the fairness of prices.

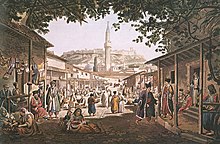

[4][5] Open air and public markets were known in ancient Babylonia, Assyria, Phoenicia, the Land of Israel, Greece, Egypt, and the Arabian peninsula.

A vast array of goods were traded, including salt, lapis lazuli, dyes, cloth, metals, pots, ceramics, statues, spears, and other implements.

[12] The Greek historian Herodotus noted that in Egypt, roles were reversed compared with other cultures, and Egyptian women frequented the market and carried on trade, while the men remained at home weaving cloth.

[17] At the agora in Athens, officials were employed by the government to oversee weights, measures, and coinage to ensure that the people were not cheated in market place transactions.

Priories and aristocratic manorial households created considerable demand for goods and services, both luxuries and necessities, and also afforded some protection to merchants and traders.

Over time, permanent shops began opening daily and gradually supplanted the periodic markets, while peddlers or itinerant sellers continued to fill in any gaps in distribution.

In response to competitive pressures, towns invested in developing a reputation for quality produce, efficient market regulation and good amenities for visitors such as covered accommodation.

The 18th century commentator Daniel Defoe visited Sturbridge fair in 1723 and wrote a lengthy description which paints a picture of a highly organised, vibrant operation which attracted large number of visitors from some distance away.

Qi's Prime Minister, the great reformer, Guan Zhong, divided the capital into 21 districts (xiang) of which three were dedicated to farmers, three to hand-workers and three to businessmen, who were instructed to settle near the markets.

[46][47][48] Vendors were arranged according to the type of commodity offered,[49] and markets were strictly regulated with departments responsible for security, weights and measures, price-fixing, and certificates.

One anecdote from the time of Empress Wu relates the tale of a fourth rank official who missed out on the opportunity for promotion after he was seen purchasing a steamed pancake from a market.

[56] Since circa 3000 BCE, bazaars have dominated the Middle East - respectively extending to Northern Africa - as regards to numerous areas from retail towards resources, with trade amongst merchants commonplace, likewise with bartering amongst participants.

Given such dense activity, bazaars became an attraction for foreigners in exchanging resources, such as spices, textiles, labour, et cetera, drawing the attention of Arabs, Turks, Greeks, Persians, Jews as well as Indians, not to mention Westerners since the late-16th to early-17th centuries.

[58] Local markets where people purchased their daily necessities were known as tianguis, while a pochteca was a professional merchant who travelled long distances to obtain rare goods or luxury items desired by the nobility.

Europeans often saw Orientals as the photographic negative of Western civilisation; the peoples could be threatening – they were "despotic, static and irrational whereas Europe was viewed as democratic, dynamic and rational".

Bats, rats and lizards dried in the sun, palm wine and fruit, form the must luxurious entertainments, and stand continually for sale in the streets.

The government made some attempts to build markets in the north of the country, but that was largely unsuccessful and most commercial buyers travel to Johannesburg or Tshwane for supplies.

It is anticipated that these hubs will assist in curbing the number of sellers who take their produce to South Africa where it is placed on cold storage, only to be imported back into the country at a later date.

Although large, vertically integrated food retailers, such as supermarkets, are beginning to make inroads into the supply chain, traditional hawkers and produce markets have shown remarkable resilience.

Produce markets in Asia are undergoing major changes as supermarkets enter the retail scene and the growing middle classes acquire preferences for branded goods.

[102] In South Asia, especially Nepal, India, and Bangladesh, a haat (also known as hat), refers to a regular rural produce market, typically held once or twice per week.

In parts of Malaysia, jungle produce markets trade in indigenous fruits and vegetables, all of which are gaining popularity as consumers switch to pesticide-free food products.

[116] The Cubao Farmers Market, in Quezon City gained international attention following a feature spot on the cable network program, No Reservations, with Anthony Bourdain in 2009.

[125] Les Halles, a vast centralised wholesale market, was known to be in existence at least by the 13th century when it was expanded, and was demolished in 1971 to make way for an underground shopping precinct.

In central London, costermongers worked along designated routes, selling door-to-door or by trading from some 36 unauthorised, but highly organised markets situated along major thoroughfares or meeting places such as Whitecross Street, Covent Garden and Leather Lane.

Street vendors roam around in search of a suitable venue such as a plaza, entrance to a railway station or beach front where they lay their goods out on mats.

Popular with both locals and visitors, a distinctive feature is the quality of fresh fish and seafood, which once purchased can be taken to the street stalls around the perimeter of the market who will cook it to order.