Maryland campaign

He undertook the risky maneuver of splitting his army so that he could continue north into Maryland while simultaneously capturing the Federal garrison and arsenal at Harpers Ferry.

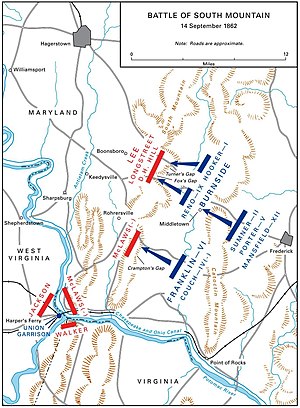

While Confederate Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson surrounded, bombarded, and captured Harpers Ferry (September 12–15), McClellan's army of 102,000 men attempted to move quickly through the South Mountain passes that separated him from Lee.

The Battle of South Mountain on September 14 delayed McClellan's advance and allowed Lee sufficient time to concentrate most of his army at Sharpsburg.

Lee, outnumbered two to one, moved his defensive forces to parry each offensive blow, but McClellan never deployed all of the reserves of his army to capitalize on localized successes and destroy the Confederates.

President Abraham Lincoln used this Union victory as the justification for announcing his Emancipation Proclamation, which effectively ended any threat of European support for the Confederacy.

Lee's Maryland campaign can be considered the concluding part of a logically connected, three-campaign, summer offensive against Federal forces in the Eastern Theater.

Lee knew the Confederacy did not have to win the war by defeating the North militarily; it merely needed to make the Northern populace and government unwilling to continue the fight.

With the Congressional elections of 1862 approaching in November, Lee believed that an invading army playing havoc inside the North could tip the balance of Congress to the Democratic Party, which might force Abraham Lincoln to negotiate an end to the war.

Nevertheless, the news of the victory at Second Bull Run and the start of Lee's invasion caused considerable diplomatic activity between the Confederate States and France and the United Kingdom.

[9] Additionally, generals Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith in the Western Theatre outmaneuvered Don Carlos Buell to reach the border state of Kentucky from eastern Tennessee through the Battle of Richmond which coincided with Confederate victories in the East.

Aside from the Pennsylvania Reserves, which had born the brunt of action in the Seven Days Battles, none of these troops had served under McClellan before, all had been poorly led, and did not have much record of battlefield success.

The V Corps was heavily engaged in the Seven Days Battles and at Second Bull Run, and had lost significant amounts of men; several new regiments of green troops would replace them.

Along with the marching into Maryland, the manpower of the army dropped even more due to straggling, lack of food, and a significant number of soldiers in Virginia regiments deserting on the grounds that they had signed up to defend their state and not invade the North.

The lack of food was a serious problem for the Army of Northern Virginia, as most crops were a month away from harvesting in September and many soldiers were forced to subsist on field corn and green apples, which gave them indigestion and diarrhea.

[17] Jefferson Davis sent to all three generals a draft public proclamation, with blank spaces available for them to insert the name of whatever state their invading forces might reach.

Lee's proclamation announced to the people of Maryland that his army had come "with the deepest sympathy [for] the wrongs that have been inflicted upon the citizens of the commonwealth allied to the States of the South by the strongest social, political, and commercial ties ... to aid you in throwing off this foreign yoke, to enable you again to enjoy the inalienable rights of freemen.

[24] Some troops refused to cross the Potomac River because an invasion of Union territory violated their beliefs that they were fighting only to defend their states from "Northern aggression".

Countless others became ill with diarrhea after eating unripe corn from the Maryland fields or disabled because their shoeless feet were bloodied on hard-surfaced Northern roads.

[22] Lee ordered his commanders to deal harshly with stragglers, whom he considered cowards "who desert their comrades in peril" and were therefore "unworthy members of an army that has immortalized itself" in its recent campaigns.

When Genl McClellan came thro[ugh] the ladies nearly eat him up, they kissed his clothing, threw their arms around his horse's neck and committed all sorts of extravagances.

[32] The army started with relatively low morale, a consequence of its defeats on the Peninsula and at Second Bull Run, but upon crossing into Maryland, their spirits were boosted by the "friendly, almost tumultuous welcome" that they received from the citizens of the state.

[36] Lee, seeing McClellan's uncharacteristic aggressive actions, and possibly learning through a Confederate sympathizer that his order had been compromised,[37] quickly moved to concentrate his army.

McClellan's limited activity on September 15 after his victory at South Mountain, however, condemned the garrison at Harpers Ferry to capture and gave Lee time to unite his scattered divisions at Sharpsburg.

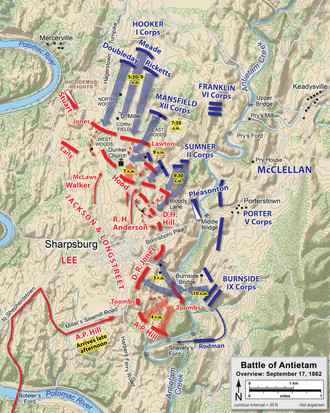

Attacks and counterattacks swept across the Miller Cornfield and the woods near the Dunker Church as Maj. Gen. Joseph K. Mansfield's XII Corps joined to reinforce Hooker.

Union assaults against the Sunken Road ("Bloody Lane") by Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner's II Corps eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not pressed.

Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and counterattacked, driving back Burnside's men and saving Lee's army from destruction.

[43] On September 19, a detachment of Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter's V Corps pushed across the river at Boteler's Ford, attacked the Confederate rear guard commanded by Brig.

He was even more astonished that from September 17 to October 26, despite repeated entreaties from the War Department and the president, McClellan declined to pursue Lee across the Potomac, citing shortages of equipment and the fear of overextending his forces.

General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck wrote in his official report, "The long inactivity of so large an army in the face of a defeated foe, and during the most favorable season for rapid movements and a vigorous campaign, was a matter of great disappointment and regret.

It forced the end of Lee's strategic invasion of the North and gave Abraham Lincoln the victory he was awaiting before announcing the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, which took effect on January 1, 1863.