Maryland in the American Civil War

Abolition of slavery in Maryland came before the end of the war, with a new third constitution voted approval in 1864 by a small majority of Radical Republican Unionists then controlling the nominally Democratic state.

There was much less appetite for secession than elsewhere in the Southern States (South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, Tennessee) or in the border Southern states (Kentucky and Missouri) of the Upper South,[2] but Maryland was equally unsympathetic towards the potentially abolitionist position of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln.

[8] Other residents, and a majority of the legislature, wished to remain in the Union, but did not want to be involved in a war against their southern neighbors, and sought to prevent a military response by Lincoln to the South's secession.

[9] After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, many citizens began forming local militias, determined to prevent a future slave uprising.

[10] Soldiers from Pennsylvania and Massachusetts were transported by rail to Baltimore, where they had to disembark, march through the city, and board another train to continue their journey south to Washington.

Mayor George William Brown and Maryland Governor Thomas Hicks implored President Lincoln to reroute troops around Baltimore city and through Annapolis to avoid further confrontations.

[14] In a letter to President Lincoln, Mayor Brown wrote: It is my solemn duty to inform you that it is not possible for more soldiers to pass through Baltimore unless they fight their way at every step.

[14]Hearing no immediate reply from Washington, on the evening of April 19 Governor Hicks and Mayor Brown ordered the destruction of railroad bridges leading into the city from the North, preventing further incursions by Union soldiers.

For a time it looked as if Maryland was one provocation away from joining the rebels, but Lincoln moved swiftly to defuse the situation, promising that the troops were needed purely to defend Washington, not to attack the South.

[26]Butler went on to occupy Baltimore and declared martial law, ostensibly to prevent secession, although Maryland had voted solidly (53–13) against secession two weeks earlier,[27] but more immediately to allow war to be made on the South without hindrance from the state of Maryland,[25] which had also voted to close its rail lines to Northern troops, so as to avoid involvement in a war against its southern neighbors.

In this case U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice, and native Marylander, Roger B. Taney, acting as a federal circuit court judge, ruled that the arrest of Merryman was unconstitutional without Congressional authorization, which Lincoln could not then secure: The President, under the Constitution and laws of the United States, cannot suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, nor authorize any military officer to do so.

"[36] Although previous secession votes, in spring 1861, had failed by large margins,[22] there were legitimate concerns that the war-averse Assembly would further impede the federal government's use of Maryland infrastructure to wage war on the South.

The federal troops executing Judge Carmichael's arrest beat him unconscious in his courthouse while his court was in session, before dragging him out, initiating a public controversy.

[47] Captain Bradley T. Johnson refused the offer of the Virginians to join a Virginia Regiment, insisting that Maryland should be represented independently in the Confederate army.

Some, like physician Richard Sprigg Steuart, remained in Maryland, offered covert support for the South, and refused to sign an oath of loyalty to the Union.

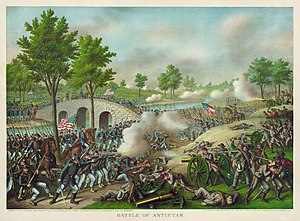

[62] The order indicated that Lee had divided his army and dispersed portions geographically (to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and Hagerstown, Maryland), thus making each subject to isolation and defeat in detail – if McClellan could move quickly enough.

[62] However, McClellan waited about 18 hours before deciding to take advantage of this intelligence and position his forces based on it, thus endangering a golden opportunity to defeat Lee decisively.

[65]Although tactically inconclusive, the Battle of Antietam is considered a strategic Union victory and an important turning point of the war, because it forced the end of Lee's invasion of the North, and it allowed President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, taking effect on January 1, 1863.

[66]Lee's setback at the Battle of Antietam can also be seen as a turning point in that it may have dissuaded the governments of France and Great Britain from recognizing the Confederacy, doubting the South's ability to maintain and win the war.

[69] Such celebrations would prove short lived, as Steuart's brigade was soon to be severely damaged at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863), a turning point in the war and a reverse from which the Confederate army would never recover.

The battle was part of Early's raid through the Shenandoah Valley and into Maryland, attempting to divert Union forces away from Gen. Robert E. Lee's army under siege at Petersburg, Virginia.

However, Wallace delayed Early for nearly a full day, buying enough time for Ulysses S. Grant to send reinforcements from the Army of the Potomac to the Washington defenses.

[71] The state capital Annapolis's western suburb of Parole became a camp where prisoners-of-war would await formal exchange in the early years of the war.

Around 70,000 soldiers passed through Camp Parole until Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant assumed command as General-in-Chief of the Union Army in 1864, and ended the system of prisoner exchanges.

In March 1862, the Maryland Assembly passed a series of resolutions, stating that: This war is prosecuted by the Nation with but one object, that, namely, of a restoration of the Union just as it was when the rebellion broke out.

The document, which replaced the Maryland Constitution of 1851, was largely advocated by Unionists who had secured control of the state, and was framed by a Convention which met at Annapolis in April 1864.

One feature of the new constitution was a highly restrictive oath of allegiance which was designed to reduce the influence of Southern sympathizers, and to prevent such individuals from holding public office of any kind.

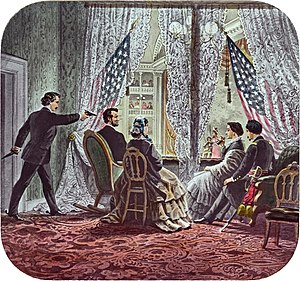

After shooting the President, Booth galloped on his horse into Southern Maryland, where he was sheltered and helped by sympathetic residents and smuggled at night across the Potomac River into Virginia a week later.

The very nomination of Abraham Lincoln, four years ago, spoke plainly war upon Southern rights and institutions... And looking upon African Slavery from the same stand-point held by the noble framers of our constitution, I for one, have ever considered it one of the greatest blessings (both for themselves and us,) that God has ever bestowed upon a favored nation… I have also studied hard to discover upon what grounds the right of a State to secede has been denied, when our very name, United States, and the Declaration of Independence, both provide for secession.

A brochure published by the home in the 1890s described it as: a haven of rest... to which they may retire and find refuge, and, at the same time, lose none of their self-respect, nor suffer in the estimation of those whose experience in life is more fortunate.