Sack of Dinant

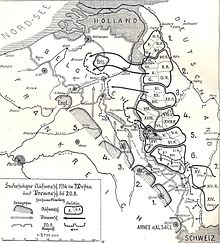

[24]The crushing defeat on August 15, which resulted in 3,000 soldiers being wounded, coupled with the playing of "La Marseillaise" after the town was liberated, exacerbated the animosity of the occupying German forces towards the local population.

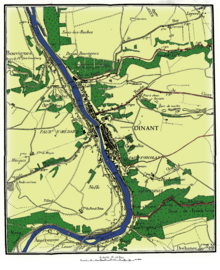

[29] The city of Dinant, situated at the bottom of a steep, narrow valley, presented challenges in identifying the source of the gunfire and tracking projectiles that ricocheted off its rocky terrain.

[33][28] This distorted perception of reality, exacerbated by the stress of battle, led to what Arie Nicolaas Jan den Hollander terms "war psychosis", driving the soldiers to engage in violent reprisals.

"[39] According to the war diary of one of the battalions involved, the raid was ordered at the brigade level with the intent to capture Dinant, expel its defenders, and cause maximum destruction.

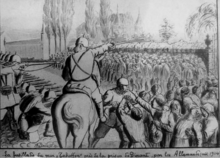

[nb 7][55] Maurice Tschoffen, a witness to the events, described how soldiers marched in two lines alongside the houses, with those on the right monitoring the left, both with their fingers on the triggers, prepared to fire at any moment.

Maurice Tschoffen, the King's Public Prosecutor in Belgium [fr], reported that the prison governor informed him that the military authorities in Berlin were convinced that no shots had been fired in Dinant.

[76][77] After the sacking of Leffe, the 178th Infantry Regiment crossed the Meuse following the withdrawal of French troops and arrived in Bouvignes-sur-Meuse, where it committed numerous violent acts resulting in the deaths of 31 individuals.

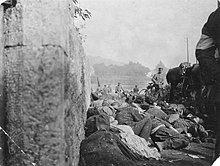

The witnesses provide evidence that:[87] The whole family was gathered at my parents' house, which backed onto the rock behind the homes of Joseph Rondelet and the widow Camille Thomas, on rue Saint-Pierre.

[90] In reply, the Cooreman government published its Grey Book of 1916, which asserted: "He is twice guilty who, after violating the rights of others, attempts to justify himself with audacity by attributing false faults to his victim.

[92] For his part, the Bishop of Namur responds to the Germans following the publication of their White Book: We are only waiting for the moment when the impartial historian can come to Dinant, see for himself what happened there, and interview the survivors.

Then the universe, which has already judged with extreme and just rigor the massacre of nearly seven hundred civilians and the destruction of an ancient city, with its monuments, archives and industries, will appreciate with even greater severity this new procedure which, to clear itself of a deserved accusation, stops at nothing and transforms unjustly sacrificed victims into assassins.

In February 1920, the Allied extradition list had 853 names[86] of chiefs of the former German regime accused of committing heinous acts against civilians, wounded or prisoners of war.

These were the words of Paul Deschanel, then President of the French Chamber, as he stood over the ruins of the town and the graves of its victims on August 23, 1919, the anniversary of the Sack of Dinant.

Dinant has paid a high enough price for this dismal honor, moreover, for it not to be haggled over; For it is not only a past of glory and prosperity that it has seen wiped out in the space of a few hours, it is not only historical memories and works of art that it has seen destroyed by the incendiary torch - other towns have suffered materially more than the Mosan city, but they are already coming back to life - no, what places the town of Dinant at the top of the long list of martyred cities is its obituary.

Notably, the former Servais house bears a commemorative plaque sculpted by Frans Huygelen portraying a bust of Christ on the cross as a tribute to the 243 Leffe victims.

Before God and before Men, on our honor and conscience, without hatred and without anger, penetrated by the importance of the oath we are about to take, we all swear that we did not, in August 1914, know, see or know of anything that could have constituted an act of illegitimate violence against the troops of the invader.The Germans destroyed it in May 1940 during World War II.

On May 6, 2001, the German government, led by Secretary of State for Defense Walter Kolbow, issued an official apology 87 years after the events in question for the atrocities committed against the Dinant population in 1914.[99][...]

I ask this because I believe that such a request is more necessary than ever, precisely at a time when the process of European unification is intensifying, a Europe in which our two countries are jointly pursuing a policy aimed at preventing the recurrence of such crimes and suffering.

[100]The local authorities stated that granting forgiveness in the name of the deceased was not within their purview, but they appreciated the effort to reconcile and move forward, particularly for the benefit of younger generations.

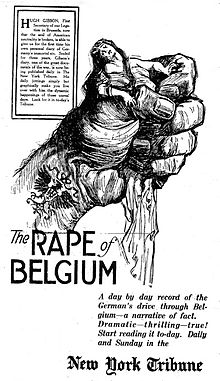

[83] The press, predominantly British but also including that of neutral nations, disseminated firsthand accounts from civilians and informative pamphlets that condemned the actions of the German Heer.

Occasionally, the desire for emphasis led some journalists to extend their assertions, as noted by Edouard Gérard:[103] People of letters more concerned, it seems, with 'monetizing our disaster' - the expression is not mine - than with contributing to "bringing the truth to light", have already published high fantasy accounts.

[90] The German White Book, published in February 1915, claimed that imperial troops encountered francs-tireurs who were allegedly organized, armed, and trained by thehe Belgian government.

According to the White Book, these francs-tireurs, comprising both men and women, and even children, conducted numerous covert attacks on German troops, leading to substantial losses.

[105] Cardinal Mercier had earlier called for the collection of accurate and objective information regarding the atrocities committed by the Germans, independent of the State's efforts in producing the Grey Book.

Thomas-Louis Heylen appointed his secretary, Canon Jean Schmitz, to gather testimonies and documents to provide a detailed account of the suffering endured by Belgium due to what he termed the Germans' "monument of hypocrisy and lies.

He quickly recognized the complexity of producing a well-organized and impartial report and collaborated with the vicar-general to collect evidence, documentation, and photographic records of the perpetrators' actions.

Specifically, Belgians Fernand Mayence [fr], Jean de Sturler, and Léon van der Essen, worked alongside Germans Franz Petri, Hans Rothfels, and Werner Conze.

Utilizing primary sources, including German war diaries and eyewitness accounts, these historians have established and analyzed the facts surrounding the events.

[121] Axel Tixhon, a historian specializing in the events of August 1914, argues that Keller's work is driven by objectives that diverge from those of rigorous scientific research.

In his war diaries published in 2014, he provides a detailed account of the events of August 15, including the circumstances leading to his injury as his unit crossed the Dinant bridge (now named after him) to support the troops engaged in the battle for the citadel.