Match

[5]Another text, Wu Lin Chiu Shih, dated from 1270 AD, lists sulfur matches as something that was sold in the markets of Hangzhou, around the time of Marco Polo's visit.

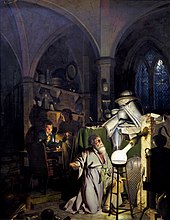

[5] Before the use of matches, fires were sometimes lit using a burning glass (a lens) to focus the sun on tinder, a method that could only work on sunny days.

Another more common method was igniting tinder with sparks produced by striking flint and steel, or by sharply increasing air pressure in a fire piston.

[6] Others, including Robert Boyle and his assistant, Ambrose Godfrey, continued these experiments in the 1680s with phosphorus and sulfur, but their efforts did not produce practical and inexpensive methods for generating fires.

His match consisted of a small glass capsule containing a chemical composition of sulfuric acid colored with indigo and coated on the exterior with potassium chlorate, all of which was wrapped up in rolls of paper.

The immediate ignition of this particular form of a match was achieved by crushing the capsule with a pair of pliers, mixing and releasing the ingredients in order for it to become alight.

In London, similar matches meant for lighting cigars were introduced in 1849 by Heurtner who had a shop called the Lighthouse in the Strand.

[13] Chemical matches were unable to make the leap into mass production, due to the expense, their cumbersome nature, and the inherent danger of using them.

Several chemical mixtures were already known that would ignite by a sudden explosion, but it had not been found possible to transmit the flame to a slow-burning substance like wood.

They consisted of wooden splints or sticks of cardboard coated with sulfur and tipped with a mixture of sulfide of antimony, chlorate of potash, and gum.

[6][19] In 1829, Scots inventor Sir Isaac Holden invented an improved version of Walker's match and demonstrated it to his class at Castle Academy in Reading, Berkshire.

Holden did not patent his invention and claimed that one of his pupils wrote to his father Samuel Jones, a chemist in London who commercialised his process.

These early matches had a number of problems – an initial violent reaction, an unsteady flame, and unpleasant odor and fumes.

Lucifers were quickly replaced after 1830 by matches made according to the process devised by Frenchman Charles Sauria, who substituted white phosphorus for the antimony sulfide.

[21] These new phosphorus matches had to be kept in airtight metal boxes but became popular and went by the name of loco foco ("crazy fire") in the United States, from which was derived the name of a political party.

[22] The earliest American patent for the phosphorus friction match was granted in 1836 to Alonzo Dwight Phillips of Springfield, Massachusetts.

From 1870 the end of the splint was fireproofed by impregnation with fire-retardant chemicals such as alum, sodium silicate, and other salts resulting in what was commonly called a "drunkard's match" that prevented the accidental burning of the user's fingers.

[24] An unsuccessful experiment by his professor, Meissner, gave Irinyi the idea to replace potassium chlorate with lead dioxide[25] in the head of the phosphorus match.

He mixed the phosphorus with lead dioxide and gum arabic, poured the paste-like mass into a jar, and dipped the pine sticks into the mixture and let them dry.

He sold the invention and production rights for these noiseless matches to István Rómer, a Hungarian pharmacist living in Vienna, for 60 florins (about 22.5 oz t of silver).

The earliest report of phosphorus necrosis was made in 1845 by Lorinser in Vienna, and a New York surgeon published a pamphlet with notes on nine cases.

Members of the Fabian Society, including George Bernard Shaw, Sidney Webb, and Graham Wallas, were involved in the distribution of the cash collected.

Anton Schrötter von Kristelli discovered in 1850 that heating white phosphorus at 250 °C in an inert atmosphere produced a red allotropic form, which did not fume in contact with air.

The company developed a safe means of making commercial quantities of phosphorus sesquisulfide in 1899 and started selling it to match manufacturers.

The United States did not pass a law, but instead placed a "punitive tax" in 1913 on white phosphorus–based matches, one so high as to render their manufacture financially impractical, and Canada banned them in 1914.

[33] The Niagara Falls plant made them until 1910, when the United States Congress forbade the shipment of white phosphorus matches in interstate commerce.

The striking surface on modern matchboxes is typically composed of 25% powdered glass or other abrasive material, 50% red phosphorus, 5% neutralizer, 4% carbon black, and 16% binder; and the match head is typically composed of 45–55% potassium chlorate, with a little sulfur and starch, a neutralizer (ZnO or CaCO3), 20–40% of siliceous filler, diatomite, and glue.

When the match is struck, the phosphorus and chlorate mix in a small amount and form something akin to the explosive Armstrong's mixture, which ignites due to the friction.

They have remained particularly popular in the United States, even when safety matches had become common in Europe, and are still widely used today around the world, including in many developing countries,[35] for such uses as camping, outdoor activities, emergency/survival situations, and stocking homemade survival kits.

They have a strikeable tip similar to a normal match, but the combustible compound – including an oxidiser – continues down the length of the stick, coating half or more of the entire matchstick.