Midwifery

"[8] The review found that midwifery-led care was associated with a reduction in the use of epidurals, with fewer episiotomies or instrumental births, and a decreased risk of losing the baby before 24 weeks' gestation.

The midwife will discuss pregnancy issues such as fatigue, heartburn, varicose veins, and other common problems such as back pain.

Blood pressure and weight are monitored and the midwife measures the mother's abdomen to see if the baby is growing as expected.

[18] Throughout labor and delivery the mother's vital signs (temperature, blood pressure, and pulse) are closely monitored and her fluid intake and output are measured.

The lithotomy position was not used until the advent of forceps in the seventeenth century and since then childbirth has progressively moved from a woman supported experience in the home to a medical intervention within the hospital.

Skin-to-skin is encouraged, as this regulates the baby's heart rate, breathing, oxygen saturation, and temperature—and promotes bonding and breastfeeding.

[citation needed] In some countries, such as Chile, the midwife is the professional who can direct neonatal intensive care units.

This is an advantage for these professionals, who can use the knowledge of perinatology to bring a high quality care of the newborn, with medical or surgical conditions.

[30] In ancient Egypt, midwifery was a recognized female occupation, as attested by the Ebers Papyrus which dates from 1900 to 1550 BCE.

Bas reliefs in the royal birth rooms at Luxor and other temples also attest to the heavy presence of midwifery in this culture.

He states in his work, Gynecology, that "a suitable person will be literate, with her wits about her, possessed of a good memory, loving work, respectable and generally not unduly handicapped as regards her senses [i.e., sight, smell, hearing], sound of limb, robust, and, according to some people, endowed with long slim fingers and short nails at her fingertips."

[34] There appears to have been three "grades" of midwives present: The first was technically proficient; the second may have read some of the texts on obstetrics and gynecology; but the third was highly trained and reasonably considered a medical specialist with a concentration in midwifery.

In fact, a number of Roman legal provisions strongly suggest that midwives enjoyed status and remuneration comparable to that of male doctors.

[33] One example of such a midwife is Salpe of Lemnos, who wrote on women's diseases and was mentioned several times in the works of Pliny.

The first is the midwifery was not a profession to which freeborn women of families that had enjoyed free status of several generations were attracted; therefore it seems that most midwives were of servile origin.

Second, since most of these funeral epitaphs describe the women as freed, it can be proposed that midwives were generally valued enough, and earned enough income, to be able to gain their freedom.

[33] The actual duties of the midwife in antiquity consisted mainly of assisting in the birthing process, although they may also have helped with other medical problems relating to women when needed.

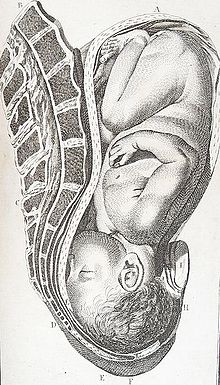

[38] In antiquity, it was believed by both midwives and physicians that a normal delivery was made easier when a woman sat upright.

Finally, the midwife received the infant, placed it in pieces of cloth, cut the umbilical cord, and cleansed the baby.

Ultimately, midwives made a determination about the chances for an infant's survival and likely recommended that a newborn with any severe deformities be exposed.

[33] A 2nd-century terracotta relief from the Ostian tomb of Scribonia Attice, wife of physician-surgeon M. Ulpius Amerimnus, details a childbirth scene.

Scribonia sits on a low stool in front of the woman, modestly looking away while also assisting the delivery by dilating and massaging the vagina, as encouraged by Soranus.

Also, many families had a choice of whether or not they wanted to employ a midwife who practiced the traditional folk medicine or the newer methods of professional parturition.

[42][43] As doctors and medical associations pushed for a legal monopoly on obstetrical care, midwifery became outlawed or heavily regulated throughout the United States and Canada.

[47] In 1846, the physician Ignaz Semmelweiss observed that more women died in maternity wards staffed by male surgeons than by female midwives, and traced these outbreaks of puerperal fever back to (then all-male) medical students not washing their hands properly after dissecting cadavers, but his sanitary recommendations were ignored until acceptance of germ theory became widespread.

[48][49] The argument that surgeons were more dangerous than midwives lasted until the study of bacteriology became popular in the early 1900s and hospital hygiene was improved.

Women began to feel safer in the setting of the hospitals with the amount of aid and the ease of birth that they experienced with doctors.

"[50] German social scientists Gunnar Heinsohn and Otto Steiger theorize that midwifery became a target of persecution and repression by public authorities because midwives possessed highly specialized knowledge and skills regarding not only assisting birth, but also contraception and abortion.

However, at the beginning of the 21st century, the medical perception of pregnancy and childbirth as potentially pathological and dangerous still dominates Western culture.

[52] The midwifery model of pregnancy and childbirth as a normal and healthy process plays a much larger role in Sweden and the Netherlands than the rest of Europe, however.