Mau movement

[2] As the movement grew, leadership came under the country's chiefly elite, the customary matai leaders entrenched in Samoan tradition and fa'a Samoa.

[4] The Mau movement culminated on 28 December 1929 in the streets of the capital Apia, when the New Zealand military police fired on a procession who were attempting to prevent the arrest of one of their members.

Broadly, the history of the Mau movement can be seen as beginning in the 19th century with European contact and the advent of Western powers, Britain, United States and Germany, vying for control of the Pacific nation.

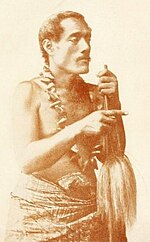

The dispute led to the eventual formation of a resistance movement called Mau a Pule on Savai'i by Lauaki Namulau'ulu Mamoe, one of the Samoan leaders from Safotulafai who was deposed by the German Governor of Samoa, Wilhelm Solf.

In 1909, Lauaki and the other senior leaders of the Mau a Pule were exiled to the German colonies in the Marianas (North West Pacific) where they were to stay until 1914, when New Zealand took over Samoa as part of its Empire duties at the outbreak of World War I.

The fleet of fautasi (canoes) embarked with Upolu's orators on board, led by the matua of Falefa, Luafalemana Moeono Taele, who after resigning his post in the administration's police force, joined the Mau.

[8] Samoans of mixed parentage, facing discrimination from both cultures but with the advantage of cross-cultural knowledge, also played a key role in the new movement.

When Nosworthy postponed his trip, Nelson organised two public meetings in Apia, which were attended by hundreds, and The Samoan League, or O le Mau, was formed.

[9] To demonstrate the extent of popular support for the Mau, Nelson organised a sports meeting for movement members on the King's Birthday, in parallel with the official event, and held a well-attended ball at his home on the same night.

Movement members had begun to engage in acts of noncooperation: Neglecting the compulsory weekly search for the rhinoceros beetle, enemy of the coconut palm, thereby threatening the lucrative copra industry.

When New Zealand administrators imposed a per-capita beetle quota, many Samoan villages resisted by breeding the insects in tightly woven baskets rather than comply with the orders to scour the forests and collect them.

In 1927, alarmed at the growing strength of the Mau, George Richardson, the administrator of Samoa, changed the law to allow the deportation of Europeans or part-Europeans charged with fomenting unrest.

Following another visit to New Zealand to petition the Government, Nelson was exiled from Samoa along with two other part-European Mau leaders, Alfred Smyth and Edwin Gurr.

[10][11] The petition, which led to the formation of a joint select committee to investigate the situation in Samoa, quoted an ancient Samoan proverb: "We are moved by love, but never driven by intimidation."

They boycotted imported products, refused to pay taxes and formed their own "police force", picketing stores in Apia to prevent the payment of customs to the authorities.

As the select committee was forced to admit, "a very substantial proportion of Samoans had joined the Mau, a number quite sufficient, if they determined to resist and thwart the activities of the Administration, to paralyse the functions of government."

The new administrator, Stephen Allen, replaced the marines with a special force of New Zealand police, and began to target the leaders of the movement.

Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III, who had led the movement following the exile of Nelson, was arrested for non-payment of taxes and imprisoned for six months.

On 29 December 1929 – which would be known thereafter as "Black Saturday" – New Zealand military police fired upon a peaceful demonstration which had assembled to welcome home Alfred Smyth, a European movement leader returning to Samoa after a two-year exile.

Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III had rushed to the front of the crowd and turned to face his people; he called for peace from them because some were throwing stones at the police.

Among the wounded were terrified women and children who had fled to a market place for cover from New Zealand police firing from the verandah of the station, one of them wielding a Lewis machine-gun.

As he lay dying, Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III knew that a bloody conflict would ensue between the Mau and New Zealand forces as a result of his death.

Recognising the need for peaceful resistance if the Mau was to achieve its goal, Tamasese made this statement to his followers: "My blood has been spilt for Samoa, I am proud to give it.

After his burial, the Colonel Allen visited Vaimoso with a troop of special police in a show of force and chastised the Mau leadership.

[12] Following the massacre, the NZ police continued to use excessive force against the Mau men, going so far as to raid their homes and villages in order to capture and arrest them.

The women's swift response to the tragic events of Black Saturday was made evident across the Pacific through Mau leader Taisi Olaf Nelson's telegram to New Zealand's Labor Party:

The day after his funeral, his village was raided by New Zealand military police; they ransacked houses, including those of the Tamasese's mourning widow and children.

The Mau no longer trusted New Zealand police, and this fear only got worse after a 16-year-old unarmed Samoan was shot and killed while running away from a marine, whose excuse he thought the boy was going to throw a stone was accepted as an adequate defence and no charges were laid.

General Hart ordered police raids on the Mau's headquarters at Vaimoso and Nelson's residence at Tuaefu, which occurred on 15 November 1933.

The apology covered the influenza epidemic of 1918, the shooting of unarmed Mau protesters by New Zealand police in 1929 and the banishing of matai (chiefs) from their homes.