Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus or Tomb of Mausolus[a] (Ancient Greek: Μαυσωλεῖον τῆς Ἁλικαρνασσοῦ; Turkish: Halikarnas Mozolesi) was a tomb built between 353 and 351 BC in Halicarnassus (present Bodrum, Turkey) for Mausolus, an Anatolian from Caria and a satrap in the Achaemenid Persian Empire, and his sister-wife Artemisia II of Caria.

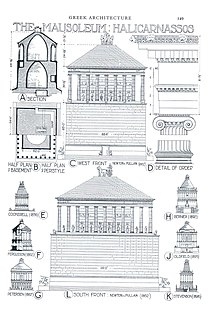

[3] The Mausoleum was approximately 45 m (148 ft) in height, and the four sides were adorned with sculptural reliefs, each created by one of four Greek sculptors: Leochares, Bryaxis, Scopas of Paros, and Timotheus.

[5] The mausoleum was considered to be such an aesthetic triumph that Antipater of Sidon identified it as one of his Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

In the 4th century BC, Halicarnassus was the capital of the small regional kingdom of Caria, within the Achaemenid Empire on the western coast of Asia Minor.

In 377 BC, the nominal ruler of the region, Hecatomnus of Milas, died and left control of the kingdom to his son, Mausolus.

After Artemisia and Mausolus, he had several other daughters and sons: Ada (adoptive mother of Alexander the Great), Idrieus, and Pixodarus.

According to the historian Pliny the Elder, the craftsmen decided to stay and finish the work after the death of their patron "considering that it was at once a memorial of his own fame and of the sculptor's art''.

A stairway flanked by stone lions led to the top of the platform, which bore along its outer walls many statues of gods and goddesses.

At the center of the platform, the marble tomb rose as a square tapering block to one-third of the Mausoleum's 45 m (148 ft) height.

This section was covered with bas-reliefs showing action scenes, including the battle of the centaurs with the lapiths and Greeks in combat during the Amazonomachy.

Perched on the top was a quadriga: four massive horses pulling a chariot in which rode images of Mausolus and Artemisia.

[8] Pausanias adds that the Romans considered the Mausoleum one of the greatest wonders of the world and it was for that reason that they called all their magnificent tombs mausolea, after it.

[9] However, Luttrell notes[10] that at that time, the local Greeks and Turks had no name for – or legends to account for – the colossal ruins, suggesting a destruction at a much earlier period.

This site was originally indicated by Professor Donaldson and was discovered definitively by Charles Newton, after which an expedition was sent by the British government.

[8] This monument was ranked the seventh wonder of the world by the ancients, not because of its size or strength but because of the beauty of its design and how it was decorated with sculpture or ornaments.

[13] The mausoleum was Halicarnassus's principal architectural monument, standing in a dominant position on rising ground above the harbor.

[8] A jar in calcite or alabaster, an alabastron, with the quadrilingual signature of Achaemenid ruler Xerxes I (ruled 486–465 BC) was discovered in the ruins of the Mausoleum, at the foot of the western staircase.

[14] The vase contains an inscription in Old Persian, Egyptian, Babylonian, and Elamite:[14][15][16] 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 𐏐 𐏋 𐏐 𐎺𐏀𐎼𐎣 ( Xšayāršā : XŠ : vazraka) "Xerxes : The Great King."

[16] In particular, the precious jar may have been offered by Xerxes to the Carian dynast Artemisia I, who had acted with merit as his only female Admiral during the Second Persian invasion of Greece, and particularly at the Battle of Salamis.

He likely meant cubits which would match Pliny's dimensions exactly but this text is largely considered corrupt and is of little importance.

[19] The semi-colossal female heads may have belonged to the acroteria of the two gables which may have represented the six Carian towns incorporated in Halicarnassus.

Suleiman the Magnificent conquered the base of the knights on the island of Rhodes, who then relocated first briefly to Sicily and later permanently to Malta, leaving the Castle and Bodrum to the Ottoman Empire.

[citation needed] During the fortification work, a party of knights entered the base of the monument and discovered the room containing a great coffin.

Also, the museum states that it is most likely that Mausolus and Artemisia were cremated, so only an urn with their ashes was placed in the grave chamber.

[citation needed] Before grinding and burning much of the remaining sculpture of the Mausoleum into lime for plaster, the Knights removed several of the best works and mounted them in the Bodrum castle.

Newton then excavated the site and found sections of the reliefs that decorated the wall of the building and portions of the stepped roof.

Because the statues were of people and animals, the Mausoleum holds a special place in history, as it was not dedicated to the gods of Ancient Greece.

Some of the surviving sculptures at the British Museum include fragments of statues and many slabs of the frieze showing the battle between the Greeks and the Amazons.

Modern buildings whose designs were based upon or influenced by interpretations of the design of the Mausoleum of Mausolus include Fourth and Vine Tower in Cincinnati; the Civil Courts Building in St. Louis; the National Newark Building in Newark, New Jersey; Grant's Tomb and 26 Broadway in New York City; Los Angeles City Hall; the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne; the spire of St. George's Church, Bloomsbury in London; the Indiana War Memorial (and in turn Salesforce Tower) in Indianapolis;[25][26] the House of the Temple in Washington D.C.; the National Diet in Tokyo; the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall in Pittsburgh;[27] and the Commerce Bank Building in Peoria, IL.