Medical image computing

This field develops computational and mathematical methods for solving problems pertaining to medical images and their use for biomedical research and clinical care.

The main goal of MIC is to extract clinically relevant information or knowledge from medical images.

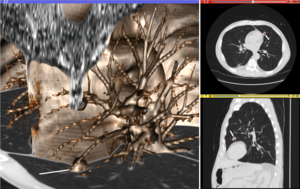

Fan-like images due to modalities such as curved-array ultrasound are also common and require different representational and algorithmic techniques to process.

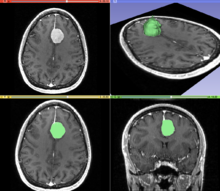

In medical imaging, these segments often correspond to different tissue classes, organs, pathologies, or other biologically relevant structures.

The optimization procedure updates the transformation of the source image based on a similarity value that evaluates the current quality of the alignment.

Medical images can vary significantly across individuals due to people having organs of different shapes and sizes.

However, an atlas can also include richer information, such as local image statistics and the probability that a particular spatial location has a certain label.

New medical images, which are not used during training, can be mapped to an atlas, which has been tailored to the specific application, such as segmentation and group analysis.

The main drawback of a single-template approach is that if there are significant differences between the template and a given test image, then there may not be a good way to map one onto the other.

[36] Statistical methods combine the medical imaging field with modern Computer Vision, Machine Learning and Pattern Recognition.

Over the last decade, several large datasets have been made publicly available (see for example ADNI, 1000 functional Connectomes Project), in part due to collaboration between various institutes and research centers.

This increase in data size calls for new algorithms that can mine and detect subtle changes in the images to address clinical questions.

Such clinical questions are very diverse and include group analysis, imaging biomarkers, disease phenotyping and longitudinal studies.

In the Group Analysis, the objective is to detect and quantize abnormalities induced by a disease by comparing the images of two or more cohorts.

Additionally, changes in biochemical (functional) activity can be observed using imaging modalities such as Positron Emission Tomography.

The null hypothesis typically assumes that the two cohorts are drawn from the same distribution, and hence, should have the same statistical properties (for example, the mean values of two groups are equal for a particular voxel).

Clinicians, on the other hand, are often interested in early diagnosis of the pathology (i.e. classification,[40][41]) and in learning the progression of a disease (i.e. regression [42]).

[44] The main difficulties are as follows: Image-based pattern classification methods typically assume that the neurological effects of a disease are distinct and well defined.

Shape analysis recently become of increasing interest to the medical community due to its potential to precisely locate morphological changes between different populations of structures, i.e. healthy vs pathological, female vs male, young vs elderly.

Image-based modelling, be it of biomechanical or physiological nature, can therefore extend the possibilities of image computing from a descriptive to a predictive angle.

In this specific context, molecular, biological, and pre-clinical imaging render additional data and understanding of basic structure and function in molecules, cells, tissues and animal models that may be transferred to human physiology where appropriate.

A number of sophisticated mathematical methods have entered medical imaging, and have already been implemented in various software packages.

These include approaches based on partial differential equations (PDEs) and curvature driven flows for enhancement, segmentation, and registration.

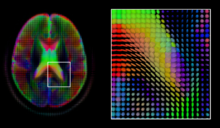

As each acquisition is associated with multiple volumes, diffusion MRI has created a variety of unique challenges in medical image computing.

Due to the simplicity of this model, a maximum likelihood estimate of the diffusion tensor can be found by simply solving a system of linear equations at each location independently.

[66] However, due to the relatively low resolution of diffusion MRI, many of these pathways may cross, kiss or fan at a single location.

As with the diffusion tensor, volumes valued with these complex models require special treatment when applying image computing methods, such as registration[72][73][74] and segmentation.

In this context there is a relatively active exchange among neuroscience, computational biology, statistics, and machine learning communities.

A body of work and tools exist to perform normalization based on anatomy (FSL, FreeSurfer, SPM).