Medicare Part D

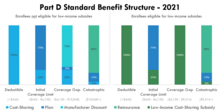

The amount of cost-sharing an enrollee pays depends on the retail cost of the filled drug, the rules of their plan, and whether they are eligible for additional Federal income-based subsidies.

Prior to 2010, enrollees were required to pay 100% of their retail drug costs during the coverage gap phase, commonly referred to as the "doughnut hole.” Subsequent legislation, including the Affordable Care Act, “closed” the doughnut hole from the perspective of beneficiaries, largely through the creation of a manufacturer discount program.

[6] Through the Part D program, Medicare finances more than one-third of retail prescription drug spending in the United States.

Medicare offers an interactive online tool [11] that allows for comparison of coverage and costs for all plans in a geographic area.

The tool lets users input their own list of medications and then calculates personalized projections of the enrollee's annual costs under each plan option.

This is because the standard benefit requires plans to include additional amounts, such as manufacturer discounts, when determining if the Out-of-Pocket Threshold has been met.

For 2022, costs for stand-alone Part D plans in the 10 major U.S. markets ranged from a low of $6.90-per-month (Dallas and Houston) to as much as $160.20-per-month (San Francisco).

The subsidy is a feature of Medicare Part D, designed to help retirees access affordable prescription medications.

[21] Low-income subsidy enrollees represent about one-quarter of enrollment,[22] but about half of the program's retail drug spending.

Part D plans that follow the formulary classes and categories established by the United States Pharmacopoeia will pass the first discrimination test.

By 2011 in the United States a growing number of Medicare Part D health insurance plans had added the specialty tier.

While some earlier drafts of the Medicare legislation included an outpatient drug benefit, those provisions were dropped due to budgetary concerns.

[29] In response to criticism regarding this omission, President Lyndon Johnson ordered the formation of the Task Force on Prescription Drugs.

[31] Despite the findings and recommendations of the Task Force, initial efforts to create a Medicare outpatient drug benefit were unsuccessful.

In 1988, the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act temporarily expanded program benefits to include self-administered drugs.

[33] In the decades following Medicare's passage, prescription drug spending grew and became increasingly financed through third-party payment.

[34] This growth was partially spurred by the launch of many billion dollar “blockbuster drugs” like Lipitor, Celebrex, and Zoloft.

In the 2000 presidential election, both the Democratic and Republican candidates campaigned on the promise of using the projected federal budget surplus to fund a new Medicare drug entitlement program.

[37] Following his electoral victory, President George W. Bush promoted a general vision of using private health plans to provide drug coverage to Medicare beneficiaries.

To keep the plan's cost projections below the $400 billion constraint set by leadership, policymakers devised the infamous “donut hole.” After exceeding a modest deductible, beneficiaries would pay 25% cost-sharing for covered drugs.

[30] However, once their spending reached an “initial coverage limit,” originally set at $2,250, their cost-sharing would return to 100% of the drug's cost.

These offsets included both state payments made on behalf of Medicare beneficiaries who also qualify for full Medicaid benefits and additional premiums paid by high-income enrollees.

[44] A 2008 study found that the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries who reported forgoing medications due to cost dropped with Part D, from 15.2% in 2004 and 14.1% in 2005 to 11.5% in 2006.

[46][47] A parallel study found that Part D beneficiaries skip doses or switch to cheaper drugs and that many do not understand the program.

[50] It was also found that there were no significant changes in trends in the dual eligibles' out-of-pocket expenditures, total monthly expenditures, pill-days, or total number of prescriptions due to Part D.[51] A 2020 study found that Medicare Part D led to a sharp reduction in the number of people over the age of 65 who worked full-time.

Numerous critics view this as a mismanagement of taxpayer funds, whereas proponents contend that allowing price negotiation might inhibit innovation by reducing profits for pharmaceutical companies.

Economist Joseph Stiglitz in his book entitled The Price of Inequality estimated a "middle-cost scenario" of $563 billion in savings "for the same budget window".

[57]: 48 Former Congressman Billy Tauzin, R–La., who steered the bill through the House, retired soon after and took a $2 million a year job as president of Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), the main industry lobbying group.

[60] In response, free-market think tank Manhattan Institute issued a report by professor Frank Lichtenberg that said the VA National Formulary excludes many new drugs.