Medieval European magic

The term "magic" in the Middle Ages encompassed a variety of concepts and practices, ranging from mystical rituals calling upon supernatural forces to herbal medicine and other mundane applications of what are today considered the natural sciences.

[1] Magic could have both positive and negative connotations, and could be practiced across European society by monks, priests, physicians, surgeons, midwives, folk healers, and diviners.

Magic practices such as divination, interpretation of omens, sorcery, and use of charms had been specifically forbidden in Mosaic Law[4] and condemned in Biblical histories of the kings.

[9] Christian theologians believed that there were multiple different forms of magic, the majority of which were types of divination, for instance, Isidore of Seville produced a catalogue of things he regarded as magic in which he listed divination by the four elements i.e. geomancy, hydromancy, aeromancy, and pyromancy, as well as by observation of natural phenomena e.g. the flight of birds and astrology.

[9] The later Middle Ages saw words for these practitioners of harmful magical acts appear in various European languages: sorcière in French, Hexe in German, strega in Italian, and bruja in Spanish.

[16] Magic is a major component and supporting contribution to the belief and practice of spiritual, and in many cases, physical healing throughout the Middle Ages.

Emanating from many modern interpretations lies a trail of misconceptions about magic, one of the largest revolving around wickedness or the existence of nefarious beings who practice it.

[20] The divine right of kings in England was thought to be able to give them "sacred magic" power to heal thousands of their subjects from sicknesses.

[24] As revealed in his last literary work, the Nomoi or Book of Laws, which he only circulated among close friends, he rejected Christianity in favour of a return to the worship of the classical Hellenic Gods, mixed with ancient wisdom based on Zoroaster and the Magi.

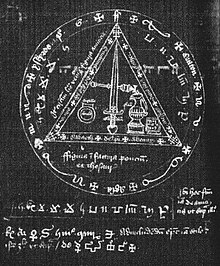

[26] Diversified instruments or rituals used in medieval magic include, but are not limited to: various amulets, talismans, potions, as well as specific chants, dances, and prayers.

[27] Archaeology is contributing to a fuller understanding of ritual practices performed in the home, on the body and in monastic and church settings.

[30] Modern scholarship continues to debate on how to classify the various forms of medieval European magic, although several terms have emerged.

[31] The presence of astrology in the Middle Ages is recorded on the walls of the San Miniato al Monte basilica in Florence, Italy.

[33] Prayers, blessings, and adjurations were all common forms of verbal formulas whose intentions were hard to distinguish between the magical and the religious.

Adjurations, which is defined as the process of making an oath, are also used as exorcisms were more directed to either a sickness, or the agent responsible such as a worm, ghost, demon, or fairy of a mischievous or malevolent nature.

[3] One example of a book that gave recipes and descriptions of plants, animals, and minerals was referred to as a “leechbook”, or a doctor-book that included Masses to be said to bless the healing herbs.

A cleric or priest who sought knowledge or influence would learn and practice from a book of magic in order to call upon the aid of angels.

[36] The thirteenth century Notory Art claims to enhance its practitioner's mental and spiritual faculties, improve one's ability to communicate with angels through dreams, and grant earthly and heavenly knowledge.

The fourteenth century Sworn Book of Honorius presents a magical system for attaining the divine vision of God and communicating with angels and other spirits for practical advantages and power.

Lastly, the fifteenth century Almandal has a special altar made of either metal or wax designed for the purpose of summoning angels or spirits of "the altitudes" which correspond to the signs of the zodiac.

1010):[39][40][41] Witches still go to cross-roads and to heathen burials with their delusive magic and call to the devil; and he comes to them in the likeness of the man that is buried there, as if he arises from death.

[47] It was only beginning in the 1150s that the Church turned its attention to defining the possible roles of spirits and demons, especially with respect to their sexuality and in connection with the various forms of magic which were then believed to exist.

He declared that all who practiced sorcery or divination would become slaves to the Church, and all those who sacrificed to the Devil or Germanic gods would be executed.

The document states that those accused of some type of sorcery were to be examined by the archpriest of the diocese in hopes of prompting a confession.