Scotland in the Middle Ages

However, the Auld Alliance with France led to the heavy defeat of a Scottish army at the Battle of Flodden in 1513 and the death of the king James IV, which would be followed by a long minority and a period of political instability.

The Church in Scotland always accepted papal authority (contrary to the implications of Celtic Christianity), introduced monasticism, and from the eleventh century embraced monastic reform, developing a flourishing religious culture that asserted its independence from English control.

[23] It was Máel Coluim III, who acquired the nickname "Canmore" (Cenn Mór, "Great Chief"), which he passed to his successors and who did most to create the Dunkeld dynasty that ruled Scotland for the following two centuries.

[24] This marriage, and raids on northern England, prompted William the Conqueror to invade and Máel Coluim submitted to his authority, opening up Scotland to later claims of sovereignty by English kings.

[30] These reforms were pursued under his successors and grandchildren Malcolm IV of Scotland and William I, with the crown now passing down the main line of descent through primogeniture, leading to the first of a series of minorities.

By the reign of Alexander III, the Scots were in a position to annexe the remainder of the western seaboard, which they did following Haakon Haakonarson's ill-fated invasion and the stalemate of the Battle of Largs with the Treaty of Perth in 1266.

The following year William Wallace and Andrew de Moray raised forces to resist the occupation and under their joint leadership an English army was defeated at the Battle of Stirling Bridge.

[39] Despite the excommunication of Bruce and his followers by Pope Clement V, his support slowly strengthened; and by 1314 with the help of leading nobles such as Sir James Douglas and Thomas Randolph only the castles at Bothwell and Stirling remained under English control.

[43] Despite victories at Dupplin Moor and Halidon Hill, in the face of tough Scottish resistance led by Sir Andrew Murray, the son of Wallace's comrade in arms, successive attempts to secure Balliol on the throne failed.

In the early period the kings of the Scots depended on the great lords of the mormaers (later earls) and Toísechs (later thanes), but from the reign of David I sheriffdoms were introduced, which allowed more direct control and gradually limited the power of the major lordships.

[58] While knowledge of early systems of law is limited, justice can be seen as developing from the twelfth century onwards with local sheriff, burgh, manorial and ecclesiastical courts and offices of the justicar to oversee administration.

[64] By the High Middle Ages, the kings of Scotland could command forces of tens of thousands of men for short periods as part of the "common army", mainly of poorly armoured spear and bowmen.

[80] In the Late Middle Ages the problems of schism in the Catholic Church allowed the Scottish Crown to gain greater influence over senior appointments and two archbishoprics had been established by the end of the fifteenth century.

[81] While some historians have discerned a decline of monasticism in the Late Middle Ages, the mendicant orders of friars grew, particularly in the expanding burghs, to meet the spiritual needs of the population.

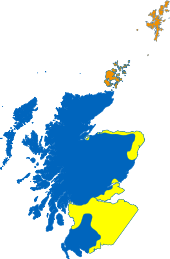

[84] The Central Lowland belt averages about 50 miles in width[85] and, because it contains most of the good quality agricultural land and has easier communications, could support most of the urbanisation and elements of conventional Medieval government.

[88] However, it also made those areas problematic to govern for Scottish kings and much of the political history of the era after the wars of independence circulated around attempts to resolve problems of entrenched localism in these regions.

[100][101] Nevertheless, craft and industry remained relatively undeveloped before the end of the Middle Ages[102] and, although there were extensive trading networks based in Scotland, while the Scots exported largely raw materials, they imported increasing quantities of luxury goods, resulting in a bullion shortage and perhaps helping to create a financial crisis in the fifteenth century.

[108] Kinship probably provided the primary unit of organisation and society was divided between a small aristocracy, whose rationale was based around warfare,[109] a wider group of freemen, who had the right to bear arms and were represented in law codes,[110] above a relatively large body of slaves, who may have lived beside and become clients of their owners.

[94] By the thirteenth century there are sources that allow greater stratification in society to be seen, with layers including the king and a small elite of mormaers above lesser ranks of freemen and what was probably a large group of serfs, particularly in central Scotland.

Our fuller sources for Ireland of the same period suggest that there would have been filidh, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge and culture in Gaelic to the next generation.

After this "de-gaelicisation" of the Scottish court, a less highly regarded order of bards took over the functions of the filidh and they would continue to act in a similar role in the Highlands and Islands into the eighteenth century.

They often trained in bardic schools, of which a few, like the one run by the MacMhuirich dynasty, who were bards to the Lord of the Isles,[126] existed in Scotland and a larger number in Ireland, until they were suppressed from the seventeenth century.

[132] Among these the most important intellectual figure was John Duns Scotus, who studied at Oxford, Cambridge and Paris and probably died at Cologne in 1308, becoming a major influence on late Medieval religious thought.

[132] These international contacts helped integrate Scotland into a wider European scholarly world and would be one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of humanism were brought into Scottish intellectual life.

[139] In the thirteenth century, French flourished as a literary language, and produced the Roman de Fergus, the earliest piece of non-Celtic vernacular literature to survive from Scotland.

[142] Before the advent of printing in Scotland, writers such as Robert Henryson, William Dunbar, Walter Kennedy and Gavin Douglas have been seen as leading a golden age in Scottish poetry.

[127] The landmark work in the reign of James IV was Gavin Douglas's version of Virgil's Aeneid, the Eneados, which was the first complete translation of a major classical text in an Anglian language, finished in 1513, but overshadowed by the disaster at Flodden.

[157] Native craftsmanship can be seen in items like the Bute mazer and the Savernake Horn, and more widely in the large number of high quality seals that survive from the mid thirteenth century onwards.

[159] Surviving copies of individual portraits are relatively crude, but more impressive are the works or artists commissioned from the continent, particularly the Netherlands, including Hugo van Der Goes's altarpiece for the Trinity College Church in Edinburgh and the Hours of James IV of Scotland.

[160] From the early fifteenth century the introduction of Renaissance styles included the selective return of Romanesque forms, as in the nave of Dunkeld Cathedral and in the chapel of Bishop Elphinstone's Kings College, Aberdeen (1500–09).