Megaliths in the Netherlands

Other grave goods included stone tools, jewelry in the form of beads and pendants, animal bones, and, in rare cases, bronze objects.

The diverse array of vessel forms and decorations permitted the identification of multiple typological levels, thereby enabling insights to be gleaned about the construction and utilization history of the graves.

The modern study of the Dutch megalithic tombs commenced in 1547 with Anthonius Schonhovius Batavus (Antony van Schoonhove), canon of the St. Donatian's Cathedral in Bruges.

His text was subsequently adopted by numerous other scholars over the following decades, with the Pillars of Heracles or the "Duvels Kut" ("Devil's Cunt", another name used for the grave near Rolde according to Schonhovius) being recorded on several maps between 1568 and 1636.

[5] The lawyer and historian Simon van Leeuwen also visited the megalithic tombs in the province of Drenthe a few years after Picardt and dedicated a section to them in his work Batavia Illustrata,[6] published posthumously in 1685.

Smids' publication of the excavation in Borger and his correspondence with Christian Schlegel led to the idea of giants as the builders of the megalithic tombs being increasingly rejected.

[10][11] In the 1730s, new levees were constructed in significant portions of the Netherlands and northwest Germany, replacing the previous ones, which were based on wooden structures that had been damaged by imported shipworms.

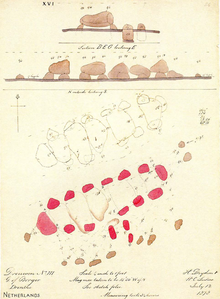

[12] In 1732, the affluent Amsterdam textile merchant Andries Schoemaker undertook a journey to Drenthe with the draughtsman Cornelis Pronk and his apprentice Abraham de Haen.

[17] In 1774, Theodorus van Brussel published a new edition of Ludolf Smids' Schatkamer der Nederlandse oudheden, which he augmented with extensive notes of his own.

[18] In 1790, Engelbertus Matthias Engelberts published the third volume of his historical work De Aloude Staat En Geschiedenissen Der Vereenigde Nederlanden, which was aimed at a general audience.

Westendorp compared the inventories of the megalithic tombs with the material remains of several ancient peoples and excluded most of them due to their use of metal tools.

The megalithic tombs were once again in jeopardy of destruction, prompting Johan Samuel Magnin, the provincial archivist of Drenthe, to submit a petition to King William II in 1841.

In contrast, Grozewinus Acker Stratingh advanced a novel theory in 1849,[29] suggesting that the tombs had been constructed by unidentified ancestors of the Celts and Germanic tribes.

[30] The most significant researcher of the 19th century was Leonhardt Johannes Friedrich Janssen (1806–1869), the curator of the Dutch antiquities collection at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden.

Gratama adopted Westendorp's erroneous assumption that the graves originally had no mounds and therefore had them removed as supposed wind drifts without documentation.

[40] Willem Pleyte, the successor of Janssen as curator at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, published a comprehensive list of the archaeological sites in the Netherlands known at the time from 1877 onwards.

[46] Subsequently, the Groningen archaeologist Albert Egges van Giffen conducted further excavations, which significantly influenced megalithic research in the Netherlands for several decades.

The exhibition, developed by Diderik van der Waals and Wiek Röhling, was initially presented in a restored farmhouse in Borger from 1967.

However, the house was destroyed by fire on two occasions, resulting in the museum's relocation to the former almshouse near the Borger large stone tomb (D27).

These investigations focused on the remains of several previously destroyed sites, the majority of which had been discovered by the amateur archaeologist Jan Evert Musch.

[50] In the 1970s, Jan Albert Bakker published his dissertation on the Western Group of the Funnelbeaker Culture, which remains an authoritative overview to this day.

[53] In the 1980s, Anna L. Brindley developed a seven-stage internal chronology system for the Funnel Beaker West group, based on the extensive pottery finds from the megalithic graves.

Megalithic burial structures were not a ubiquitous phenomenon throughout the entire distribution area, but rather were concentrated in specific regions, including Scandinavia, Denmark, northern and central Germany, northwestern Poland, and the Netherlands.

In the northern region of the province of Groningen, near the coast, the large stone tomb Heveskesklooster (G5) was discovered in 1983 beneath a terp in the municipality of Eemsdelta and subsequently relocated to the Muzeeaquarium Delfzijl.

[64] preserved destroyed references The Funnelbeaker Culture is characterized by the construction of large stone tombs, which feature mounded burial chambers built from boulders.

In Lower Saxony, the term Emsland chamber was coined for a sub-type of passage grave typical of the western group of the Funnelbeaker Culture.

[72] In the Funnelbeaker North Group, the burial chambers are frequently subdivided into multiple sections by stone slabs set vertically into the floor.

The subject was previously studied by Heinz Knöll[93] and Jan Albert Bakker,[94] who conducted important earlier work in this field.

In his investigations of the megalithic graves in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Ewald Schuldt found no evidence that the bowls there were made by members of the Funnel Beaker Culture.

Following the Early Bronze Age, the megalithic tombs appear to have been largely unused, as finds from more recent periods are exceedingly rare.