Meitnerium

The element was first synthesized in August 1982 by the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research near Darmstadt, Germany, and it was named after Lise Meitner in 1997.

Meitnerium is calculated to have properties similar to its lighter homologues, cobalt, rhodium, and iridium.

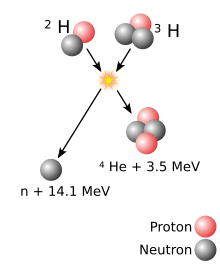

[d] This fusion may occur as a result of the quantum effect in which nuclei can tunnel through electrostatic repulsion.

[25] The definition by the IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party (JWP) states that a chemical element can only be recognized as discovered if a nucleus of it has not decayed within 10−14 seconds.

This value was chosen as an estimate of how long it takes a nucleus to acquire electrons and thus display its chemical properties.

However, its range is very short; as nuclei become larger, its influence on the outermost nucleons (protons and neutrons) weakens.

[j] Spontaneous fission, however, produces various nuclei as products, so the original nuclide cannot be determined from its daughters.

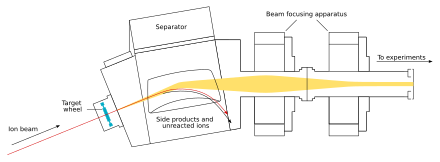

[57] The team bombarded a target of bismuth-209 with accelerated nuclei of iron-58 and detected a single atom of the isotope meitnerium-266:[58] This work was confirmed three years later at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research at Dubna (then in the Soviet Union).

Although widely used in the chemical community on all levels, from chemistry classrooms to advanced textbooks, the recommendations were mostly ignored among scientists in the field, who either called it "element 109", with the symbol of E109, (109) or even simply 109, or used the proposed name "meitnerium".

[60][61] The name meitnerium (Mt) was suggested by the GSI team in September 1992 in honor of the Austrian physicist Lise Meitner, a co-discoverer of protactinium (with Otto Hahn),[62][63][64][65][66] and one of the discoverers of nuclear fission.

Several radioactive isotopes have been synthesized in the laboratory, either by fusing two atoms or by observing the decay of heavier elements.

[4] The isotope 277Mt, created as the final decay product of 293Ts for the first time in 2012, was observed to undergo spontaneous fission with a half-life of 5 milliseconds.

Preliminary data analysis considered the possibility of this fission event instead originating from 277Hs, for it also has a half-life of a few milliseconds, and could be populated following undetected electron capture somewhere along the decay chain.

[71][72] This possibility was later deemed very unlikely based on observed decay energies of 281Ds and 281Rg and the short half-life of 277Mt, although there is still some uncertainty of the assignment.

[6] Meitnerium is expected to be a solid under normal conditions and assume a face-centered cubic crystal structure, similarly to its lighter congener iridium.

[65] Even though the half-life of 278Mt, the most stable confirmed meitnerium isotope, is 4.5 seconds, long enough to perform chemical studies, another obstacle is the need to increase the rate of production of meitnerium isotopes and allow experiments to carry on for weeks or months so that statistically significant results can be obtained.

However, the experimental chemistry of meitnerium has not received as much attention as that of the heavier elements from copernicium to livermorium.

[6][77][79] The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory attempted to synthesize the isotope 271Mt in 2002–2003 for a possible chemical investigation of meitnerium, because it was expected that it might be more stable than nearby isotopes due to having 162 neutrons, a magic number for deformed nuclei; its half-life was predicted to be a few seconds, long enough for a chemical investigation.

However, macroscopic amounts of the oxide would not sublimate until 1000 °C and the chloride would not until 780 °C, and then only in the presence of carbon aerosol particles: these temperatures are far too high for such procedures to be used on meitnerium, as most of the current methods used for the investigation of the chemistry of superheavy elements do not work above 500 °C.

[78] Following the 2014 successful synthesis of seaborgium hexacarbonyl, Sg(CO)6,[84] studies were conducted with the stable transition metals of groups 7 through 9, suggesting that carbonyl formation could be extended to further probe the chemistries of the early 6d transition metals from rutherfordium to meitnerium inclusive.