Isis

[5][6] An inscription that may refer to Isis dates to the reign of Nyuserre Ini during that period,[7] and she appears prominently in the Pyramid Texts, which began to be written down at the end of the dynasty and whose content may have developed much earlier.

[33] Yet there are signs that Hathor was originally regarded as his mother,[34] and other traditions make an elder form of Horus the son of Nut and a sibling of Isis and Osiris.

[36] In the developed form of the myth, Isis gives birth to Horus, after a long pregnancy and a difficult labor, in the papyrus thickets of the Nile Delta.

Barbara S. Lesko sees this story as a sign that Isis had the power to predict or influence future events, as did other deities who presided over birth,[45] such as Shai and Renenutet.

[52] Texts from much later times call Isis "mistress of life, ruler of fate and destiny"[45] and indicate she has control over Shai and Renenutet, just as other great deities such as Amun were said to do in earlier eras of Egyptian history.

[58] Many stories about Isis appear as historiolae, prologues to magical texts that describe mythic events related to the goal that the spell aims to accomplish.

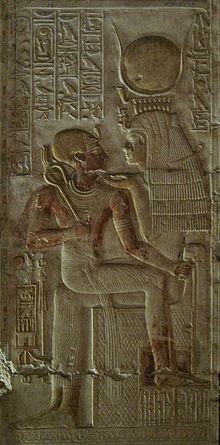

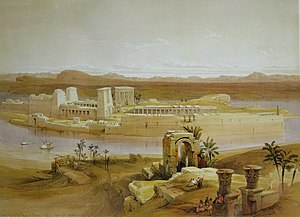

[67] In hymns inscribed at Philae she is called the "Lady of Heaven" whose dominion over the sky parallels Osiris's rule over the Duat and Horus's kingship on earth.

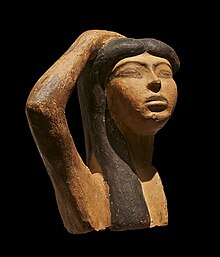

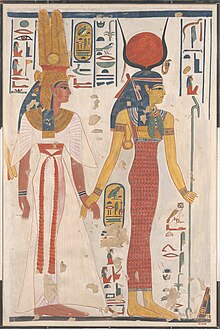

"[76] In Ancient Egyptian art, Isis was most commonly depicted as a woman with the typical attributes of a goddess: a sheath dress, a staff of papyrus in one hand, and an ankh sign in the other.

They also describe Isis as a member of the divine councils that judge souls' moral righteousness before admitting them into the afterlife, and she appears in vignettes standing beside Osiris as he presides over this tribunal.

[120] In Nubian funerary religion, Isis was regarded as more significant than her husband, because she was the active partner while he only passively received the offerings she made to sustain him in the afterlife.

[124] Hundreds of thousands of amulets and votive statues of Isis nursing Horus were made during the first millennium BCE,[125] and in Roman Egypt she was among the deities most commonly represented in household religious art, such as figurines and panel paintings.

The conquests of Alexander the Great late in that century created Hellenistic kingdoms around the Mediterranean and Near East, including Ptolemaic Egypt, and put Greek and non-Greek religions in much closer contact.

[137] Egyptian cults faced further hostility during the Final War of the Roman Republic (32–30 BCE), when Rome, led by Octavian, the future emperor Augustus, fought Egypt under Cleopatra VII.

[143] Despite being temporarily expelled from Rome during the reign of Tiberius (14–37 CE),[Note 6] the Egyptian cults gradually became an accepted part of the Roman religious landscape.

The Flavian emperors in the late first century CE treated Serapis and Isis as patrons of their rule in much the same manner as traditional Roman deities such as Jupiter and Minerva.

[150] Isis's cult, like others in the Greco-Roman world, had no firm dogma, and its beliefs and practices may have stayed only loosely similar as it diffused across the region and evolved over time.

[170] Both Plutarch and a later philosopher, Proclus, mentioned a veiled statue of the Egyptian goddess Neith, whom they conflated with Isis, citing it as an example of her universality and enigmatic wisdom.

[179] Osiris, as a dead deity unlike the immortal gods of Greece, seemed strange to Greeks and played only a minor role in Egyptian cults in Hellenistic times.

[205] Other common traits included corkscrew locks of hair and an elaborate mantle tied in a large knot over the breasts, which originated in ordinary Egyptian clothing but was treated as a symbol of the goddess outside Egypt.

Their layout was more elaborate than that of traditional Roman temples and included rooms for housing priests and for various ritual functions, with a cult statue of the goddess in a secluded sanctuary.

The first festival was the Navigium Isidis in March, which celebrated Isis's influence over the sea and served as a prayer for the safety of seafarers and, eventually, of the Roman people and their leaders.

[251] It consisted of an elaborate procession, including Isiac priests and devotees with a wide variety of costumes and sacred emblems, carrying a model ship from the local Isis temple to the sea[252] or to a nearby river.

Like its Egyptian forerunner, the Khoiak festival, the Isia included a ritual reenactment of Isis's search for Osiris, followed by jubilation when the god's body was found.

[271] In contrast, Thomas F. Mathews and Norman Muller think Isis's pose in late antique panel paintings influenced several types of Marian icons, inside and outside Egypt.

[275] Giovanni Boccaccio's biography of Isis in his 1374 work De mulieribus claris, based on classical sources, treated her as a historical queen who taught skills of civilization to humankind.

[281] It was imitated by actual rituals in various Masonic and Masonic-inspired societies during the eighteenth century, as well as in other literary works, most notably Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's 1791 opera The Magic Flute.

[285] In the dechristianization of France during the French Revolution, she served as an alternative to traditional Christianity: a symbol that could represent nature, modern scientific wisdom, and a link to the pre-Christian past.

Helena Blavatsky, the founder of the esoteric Theosophical tradition, titled her 1877 book on Theosophy Isis Unveiled, implying that it would reveal spiritual truths about nature that science could not.

The concept of a single goddess incarnating all feminine divine powers, partly inspired by Apuleius, became a widespread theme in literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

[295] Influential groups and figures in esotericism, such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in the late nineteenth century and Dion Fortune in the 1930s, adopted this all-encompassing goddess into their belief systems and called her Isis.