Memento mori

Memento mori (Latin for "remember (that you have) to die")[2] is an artistic or symbolic trope acting as a reminder of the inevitability of death.

[2] The concept has its roots in the philosophers of classical antiquity and Christianity, and appeared in funerary art and architecture from the medieval period onwards.

Often, this alone is enough to evoke the trope, but other motifs include a coffin, hourglass, or wilting flowers to signify the impermanence of life.

Often, these would accompany a different central subject within a wider work, such as portraiture; however, the concept includes standalone genres such as the vanitas and Danse Macabre in visual art and cadaver monuments in sculpture.

[5] Plato's Phaedo, where the death of Socrates is recounted, introduces the idea that the proper practice of philosophy is "about nothing else but dying and being dead".

[6] The Stoics of classical antiquity were particularly prominent in their use of this discipline, and Seneca's letters are full of injunctions to meditate on death.

[8] The Stoic Marcus Aurelius invited the reader (himself) to "consider how ephemeral and mean all mortal things are" in his Meditations.

In Psalm 90, Moses prays that God would teach his people "to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom" (Ps.

The expression memento mori developed with the growth of Christianity, which emphasized Heaven, Hell, Hades and salvation of the soul in the afterlife.

[13] The thought was then utilized in Christianity, whose strong emphasis on divine judgment, heaven, hell, and the salvation of the soul brought death to the forefront of consciousness.

[14] In the Christian context, the memento mori acquires a moralizing purpose quite opposed to the nunc est bibendum ("now is the time to drink") theme of classical antiquity.

Memento mori has been an important part of ascetic disciplines as a means of perfecting the character by cultivating detachment and other virtues, and by turning the attention towards the immortality of the soul and the afterlife.

This became a fashion in the tombs of the wealthy in the fifteenth century, and surviving examples still offer a stark reminder of the vanity of earthly riches.

Later, Puritan tomb stones in the colonial United States frequently depicted winged skulls, skeletons, or angels snuffing out candles.

Another example of memento mori is provided by the chapels of bones, such as the Capela dos Ossos in Évora or the Capuchin Crypt in Rome.

For example, Mary, Queen of Scots, owned a large watch carved in the form of a silver skull, embellished with the lines of Horace, "Pale death knocks with the same tempo upon the huts of the poor and the towers of Kings."

[17] These pieces depicted tiny motifs of skulls, bones, and coffins, in addition to messages and names of the departed, picked out in precious metals and enamel.

Especially popular in Holland and then spreading to other European nations, vanitas paintings typically represented assemblages of numerous symbolic objects such as human skulls, guttering candles, wilting flowers, soap bubbles, butterflies, and hourglasses.

In the European devotional literature of the Renaissance, the Ars Moriendi, memento mori had moral value by reminding individuals of their mortality.

Especially those facing the ever-present death during the recurring bubonic plague pandemics from the 1340s onward tried to toughen themselves by anticipating the inevitable in chants, from the simple Geisslerlieder of the Flagellant movement to the more refined cloistral or courtly songs.

The lyrics often looked at life as a necessary and God-given vale of tears with death as a ransom, and they reminded people to lead sinless lives to stand a chance at Judgment Day.

The following two Latin stanzas (with their English translations) are typical of memento mori in medieval music; they are from the virelai Ad Mortem Festinamus of the Llibre Vermell de Montserrat from 1399: Vita brevis breviter in brevi finietur, Mors venit velociter quae neminem veretur, Omnia mors perimit et nulli miseretur.

Ni conversus fueris et sicut puer factus Et vitam mutaveris in meliores actus, Intrare non poteris regnum Dei beatus.

The danse macabre is another well-known example of the memento mori theme, with its dancing depiction of the Grim Reaper carrying off rich and poor alike.

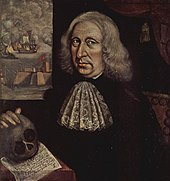

[22] Colonial American art saw a large number of memento mori images due to Puritan influence.

In his self-portrait, we see these pursuits represented alongside a typical Puritan memento mori with a skull, suggesting his awareness of imminent death.

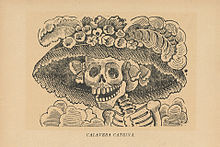

This theme was also famously expressed in the works of the Mexican engraver José Guadalupe Posada, in which people from various walks of life are depicted as skeletons.

In a practice text written by the 19th-century Tibetan master Dudjom Lingpa for serious meditators, he formulates the second contemplation in this way:[29][30] On this occasion when you have such a bounty of opportunities in terms of your body, environment, friends, spiritual mentors, time, and practical instructions, without procrastinating until tomorrow and the next day, arouse a sense of urgency, as if a spark landed on your body or a grain of sand fell in your eye.

[32] The hadith literature, which preserves the teachings of Muhammad, records advice for believers to "remember often death, the destroyer of pleasures.