Mendelian inheritance

Ronald Fisher combined these ideas with the theory of natural selection in his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, putting evolution onto a mathematical footing and forming the basis for population genetics within the modern evolutionary synthesis.

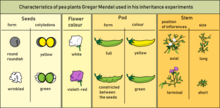

[2] The principles of Mendelian inheritance were named for and first derived by Gregor Johann Mendel,[3] a nineteenth-century Moravian monk who formulated his ideas after conducting simple hybridization experiments with pea plants (Pisum sativum) he had planted in the garden of his monastery.

Although they were not completely unknown to biologists of the time, they were not seen as generally applicable, even by Mendel himself, who thought they only applied to certain categories of species or traits.

A major roadblock to understanding their significance was the importance attached by 19th-century biologists to the apparent blending of many inherited traits in the overall appearance of the progeny,[citation needed] now known to be due to multi-gene interactions, in contrast to the organ-specific binary characters studied by Mendel.

[4] In 1900, however, his work was "re-discovered" by three European scientists, Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns, and Erich von Tschermak.

The exact nature of the "re-discovery" has been debated: De Vries published first on the subject, mentioning Mendel in a footnote, while Correns pointed out Mendel's priority after having read De Vries' paper and realizing that he himself did not have priority.

De Vries may not have acknowledged truthfully how much of his knowledge of the laws came from his own work and how much came only after reading Mendel's paper.

Its most vigorous promoter in Europe was William Bateson, who coined the terms "genetics" and "allele" to describe many of its tenets.

However, later work by biologists and statisticians such as Ronald Fisher showed that if multiple Mendelian factors were involved in the expression of an individual trait, they could produce the diverse results observed, thus demonstrating that Mendelian genetics is compatible with natural selection.

[13][14] Thomas Hunt Morgan and his assistants later integrated Mendel's theoretical model with the chromosome theory of inheritance, in which the chromosomes of cells were thought to hold the actual hereditary material, and created what is now known as classical genetics, a highly successful foundation which eventually cemented Mendel's place in history.

An important aspect of Mendel's success can be traced to his decision to start his crosses only with plants he demonstrated were true-breeding.

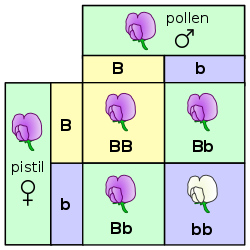

[16][17][18] Each parent carries two alleles, which can be shown on the top and the side of the chart, and each contribute one of them towards reproduction at a time.

Each of the squares in the middle demonstrates the number of times each pairing of parental alleles could combine to make potential offspring.

[16][17][18] Pedigrees are visual tree like representations that demonstrate exactly how alleles are being passed from past generations to future ones.

[19] Pedigrees can also be used to aid researchers in determining the inheritance pattern for the desired allele, because they share information such as the gender of all individuals, the phenotype, a predicted genotype, the potential sources for the alleles, and also based its history, how it could continue to spread in the future generations to come.

[20] Five parts of Mendel's discoveries were an important divergence from the common theories at the time and were the prerequisite for the establishment of his rules.

Mendel found that there are alternative forms of factors—now called genes—that account for variations in inherited characteristics.

For example, the gene for flower color in pea plants exists in two forms, one for purple and the other for white.

When sperm and egg unite at fertilization, each contributes its allele, restoring the paired condition in the offspring.

A cross between two four o'clock (Mirabilis jalapa) plants shows an exception to Mendel's principle, called incomplete dominance.

In cases of intermediate inheritance (incomplete dominance) in the F1-generation Mendel's principle of uniformity in genotype and phenotype applies as well.

[28][31][32][33][34] The Law of Segregation of genes applies when two individuals, both heterozygous for a certain trait are crossed, for example, hybrids of the F1-generation.

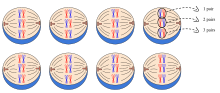

[35][27] Molecular proof of segregation of genes was subsequently found through observation of meiosis by two scientists independently, the German botanist Oscar Hertwig in 1876, and the Belgian zoologist Edouard Van Beneden in 1883.

This occurs as sexual reproduction involves the fusion of two haploid gametes (the egg and sperm) to produce a zygote and a new organism, in which every cell has two sets of chromosomes (diploid).

Because zygotes end up with a mix instead of a pre-defined "set" from either parent, chromosomes are therefore considered assorted independently.

F 2 generation: The phenotypes in the second generation show a 3 : 1 ratio.

In the genotype 25 % are homozygous with the dominant trait, 50 % are heterozygous genetic carriers of the recessive trait, 25 % are homozygous with the recessive genetic trait and expressing the recessive character.

Now two heterozygous mature individuals of such F 1 -generation are bred together. The dominant allele "E" (on the extension locus) provides black eumelanin in the coat. The recessive allele "e" (on the extension locus) hinders the storage of eumelanin in the coat, so only the pigments for the "Tan" colour are in the coat. The dominant allele S (on the S-locus) provides for the pigmentation of the entire coat. The recessive allele sP (on the S-locus) causes a white Piebald spotting . [ 37 ] Now in the puppies in the F 2 -generation all combinations are possible. The Piebald spotting and the genes for the different colour pigments are inherited independently of each other. [ 38 ] Average number ratio of phenotypes 9:3:3:1. [ 39 ]