Menstrual cup

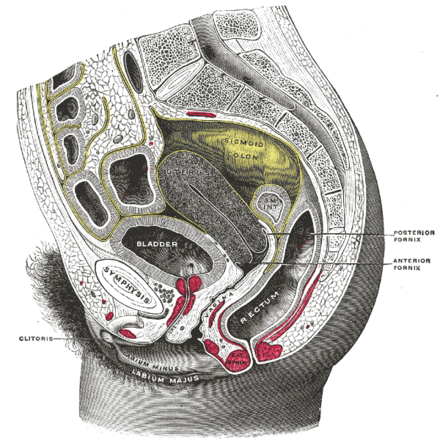

[1][2] A properly fitting menstrual cup seals against the vaginal walls, so tilting and inverting the body will not cause it to leak.

Ring-shaped cups sit in the same position as a contraceptive diaphragm; they do not block the vagina and can be worn during vaginal sex.

This generally gets better within 3–4 months of use; having friends who successfully use menstrual cups helps, but there is a shortage of research on factors that ease the learning curve.

[28] Thorough washing of the cup and hands helps to avoid introducing new bacteria into the vagina, which may heighten the risk of UTIs and other infections.

[43][44] It is possible to deliberately empty a ring-shaped menstrual disc by muscular effort, without removing it (provided it is of a fairly soft material, and the right size).

[28] Techniques like squatting, putting a leg up on the toilet seat, spreading the knees, and bearing down on the cup as if giving birth are sometimes used to make removal easier.

[54][better source needed] If it is necessary to track the amount of menses produced (e.g., for medical reasons), a bell-shaped cup allows one to do so accurately before emptying.

[63] Mason jars made for home canning are heatproof and designed to be sterilized by boiling; they have been used to steep-sterilize menstrual cups.

[18][34] Boiling menstrual cups once a month can also be a problem in developing countries, if there is a lack of water, firewood or other fuel.

[18] The 2019 review also found two reports of irritation to the vagina and cervix, neither of which had clinical consequences, and two of severe pain (one on removing a cup for the first time).

A 2019 review found the risk of toxic shock syndrome with menstrual cup use to be low, with five cases identified via their literature search (one with an IUD, one with an immunodeficiency).

[14] Data from the United States showed rates of TSS to be lower in people using menstrual cups versus high-absorbency tampons.

[28][35][7][41] Ex-vivo capacities for menstrual cups are in the range of tens of milliliters;[6][9] for comparison, a normal-size tampon or pad holds about 5mL when thoroughly soaked.

[9] They have some advantages over bell-shaped cups, including that they have a higher ex-vivo capacity (40-80ml),[106] enable bloodless period sex,[107] and are more comfortable for some users.

Firmer ring-shaped cups can be easier to get into place, as they are stiffer, but softer rings fold more easily and tightly, and may be more comfortable to insert and remove.

[117][91] As more women seek comfort and sustainability in period care, menstrual discs are rapidly emerging as a popular choice.

According to a study published in BMC Women's Health, 37% of participants reported using reusable menstrual products during their last period, signalling a strong shift towards eco-friendly alternatives.

[137] In jurisdictions where cups are classed as medical devices, the colourants generally also have to be medical-grade, and fuse permanently to the raw material so that they cannot leach out.

[137] In some cases, a broader range of colours are available in jurisdictions where menstrual cups are not classed medical devices, and food-grade dyes can be used.

Some menstrual cups carry the EU Ecolabel, which requires minimum standards for packaging, pollution, emission reduction, and toxic substances in the finished product.

[142] On the 7th of December 2017, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety approved the first menstrual cup for sale in South Korea, after a process involving the submission of data from a three-cycle clinical trial on effectiveness, and screening for ten highly hazardous volatile organic compounds.

Here, menstrual cups have an advantage over disposable pads or tampons as they do not contribute to the solid waste issues in the communities or generate embarrassing refuse that others may see.

This report was the first containing extensive information on the safety and acceptability of a widely used menstrual cup that included both preclinical and clinical testing and over 10 years of post-marketing surveillance.

[131] Some non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and companies have begun to propose menstrual cups to women in developing countries since about 2010, for example in Kenya and South Africa.

[173] Menstrual cups are regarded as a low-cost and environmentally friendly alternative to sanitary cloth, expensive disposable pads, or "nothing" – the reality for many women in developing countries.

[175] In 2022, Kumbalangi, a village in Kerala, became India's first sanitary-napkin-free panchayat under a project called "Avalkkayi", which gave away 5,700 menstrual cups for free.

[176] In 2022, the Spanish government began distributing free menstrual cups through public institutions (such as schools, prisons, and health facilities).

[177] In March 2024, Catalonia, in Spain, started supplying free menstrual cups as part of the "My period, my rules" initiative.

It is expected to reduce waste from single-use menstrual hygiene products, which had been 9000 tons[clarification needed] per year, according to the Catalan government.

[66][180] A lack of affordable hygiene products means inadequate, unhygienic alternatives are often used, which can present a serious health risk.