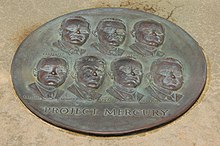

Mercury Seven

Their names were publicly announced by NASA on April 9, 1959: Scott Carpenter, Gordon Cooper, John Glenn, Gus Grissom, Wally Schirra, Alan Shepard, and Deke Slayton.

He later took leave of absence to join the U.S. Navy SEALAB project as an aquanaut, but in training suffered injuries that made him unavailable for further spaceflights.

The launch of the Sputnik 1 satellite by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957, started a Cold War technological and ideological competition with the United States known as the Space Race.

[2] American intelligence analysts assessed that the Soviets planned to put a man into orbit, which caused the United States Air Force (USAF) and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) to strengthen their efforts to achieve that goal.

[3][4] The USAF launched a spaceflight project called Man in Space Soonest (MISS), for which it obtained approval from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and requested $133 million in funding.

[8] On November 5, the Space Task Group (STG) was established at the NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, with Robert R. Gilruth as its director.

He will have continuous displays of his position and attitude and other instrument readings, and will have the capability of operating the reaction controls, and of initiating the descent from orbit.

[14] Accepting only military test pilots would simplify the selection process, and would also satisfy security requirements, as the role would almost certainly involve the handling of classified information.

[18] The first step in the selection process was to obtain the service records of test pilot school graduates from the United States Department of Defense.

Donlan, North, Gamble and psychologist Robert B. Voas then went through the records in January 1959, and identified 110 pilots – five Marines, 47 from the Navy, and 58 from the Air Force – who met the rest of the minimum standards.

Donlan, North and Gamble conducted interviews in which they asked technical questions, and queried candidates about their motivations for applying to the program.

[25][26] Then came a grueling series of physical and psychological tests at the Lovelace Clinic and the Wright Aerospace Medical Laboratory from January to March, under the direction of Albert H. Schwichtenberg, a retired USAF brigadier general.

[27] The tests included spending hours on treadmills and tilt tables, submerging their feet in ice water, three doses of castor oil, and five enemas.

[21][28][29] Only one candidate, Jim Lovell, was eliminated on medical grounds at this stage, a diagnosis that was later found to be in error;[30] thirteen others were recommended with reservations.

Of the five astronauts who had completed undergraduate degrees before being selected, two (Shepard and Schirra) were graduates of the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, in 1944 and 1945, respectively.

[21] Following a decade of intermittent studies, Cooper completed his bachelor's degree in aerospace engineering at the Air Force Institute of Technology (AFIT) in 1956.

[51][52] Despite the extensive physical examinations, Slayton had an undiagnosed atrial fibrillation, which resulted in his grounding two months prior to what would have been his first space flight, and the second orbital mission.

[54][55][56] Although the agency viewed Project Mercury's purpose as an experiment to determine whether humans could survive space travel, the seven men immediately became national heroes and were compared by Time magazine to "Columbus, Magellan, Daniel Boone, and the Wright brothers."

[57] Because they wore civilian clothes, the audience did not see them as military test pilots but "mature, middle-class Americans, average in height and visage, family men all."

To the astronauts' surprise, the reporters asked questions about their personal lives instead of their war records or flight experience, or details about Project Mercury.

[61] His selection had also tested the Navy's commitment to Project Mercury when the skipper of his ship, the USS Hornet, refused to release him, and Burke had to personally intervene.

Aware that NASA wanted to project an image of its astronauts as loving family men, and that his story would not stand up to scrutiny, he drove down to San Diego to see Trudy at the first opportunity.

After watching an Atlas rocket explode during launch on May 18, 1959, they publicly joked "I'm glad they got that out of the way" – typical gallows humor that test pilots used to cope with danger – but privately calculated that one of the seven would die during Project Mercury.

Grissom and Slayton regularly drove to Langley Air Force Base, and attempted to fly the required four hours a month, but had to compete for T-33 aircraft with colonels and generals.

[98] NASA actively sought to protect the astronauts and the agency from negative publicity and maintain an image of "clean-cut, all-American boy[s].

[100][101][28] Their official spokesman from 1959 to 1963 was NASA's public affairs officer, USAF Lieutenant Colonel John "Shorty" Powers, who as a result became known in the press as the "eighth astronaut".

[105] While Shepard prohibited junior astronauts from receiving gifts and consulting or teaching part-time, he remained vice president and part owner of the Baytown National Bank in Houston, and devoted much of his time to it.

[106] Training was always ungraded; the Mercury astronauts had nothing to gain and much to lose from being objectively compared to the newer classes, as it could threaten their privileged status, managerial control, and priority for flight assignments.

[112] Scott, Virgil, Gordon, John, and Alan Tracy from Gerry Anderson's television series Thunderbirds were named in honor of the astronauts Carpenter, Grissom, Cooper, Glenn, and Shepherd.

[114] President John F. Kennedy presented the astronaut group the 1962 Collier Trophy at the White House "for pioneering manned space flight in the United States".