Apollo program

Apollo was later dedicated to President John F. Kennedy's national goal for the 1960s of "landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth" in an address to Congress on May 25, 1961.

Overall, the Apollo program returned 842 pounds (382 kg) of lunar rocks and soil to Earth, greatly contributing to the understanding of the Moon's composition and geological history.

"[3] Silverstein chose the name at home one evening, early in 1960, because he felt "Apollo riding his chariot across the Sun was appropriate to the grand scale of the proposed program".

In July 1960, NASA Deputy Administrator Hugh L. Dryden announced the Apollo program to industry representatives at a series of Space Task Group conferences.

[6] In November 1960, John F. Kennedy was elected president after a campaign that promised American superiority over the Soviet Union in the fields of space exploration and missile defense.

Up to the election of 1960, Kennedy had been speaking out against the "missile gap" that he and many other senators said had developed between the Soviet Union and the United States due to the inaction of President Eisenhower.

At a meeting of the US House Committee on Science and Astronautics one day after Gagarin's flight, many congressmen pledged their support for a crash program aimed at ensuring that America would catch up.

[26] In September 1962, by which time two Project Mercury astronauts had orbited the Earth, Gilruth had moved his organization to rented space in Houston, and construction of the MSC facility was under way, Kennedy visited Rice to reiterate his challenge in a famous speech: But why, some say, the Moon?

We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills; because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win ...[27][b]The MSC was completed in September 1963.

But an even bigger facility would be needed for the mammoth rocket required for the crewed lunar mission, so land acquisition was started in July 1961 for a Launch Operations Center (LOC) immediately north of Canaveral at Merritt Island.

The design, development and construction of the center was conducted by Kurt H. Debus, a member of Wernher von Braun's original V-2 rocket engineering team.

The LOC also included an Operations and Checkout Building (OCB) to which Gemini and Apollo spacecraft were initially received prior to being mated to their launch vehicles.

[36] Charles Fishman, in One Giant Leap, estimated the number of people and organizations involved into the Apollo program as "410,000 men and women at some 20,000 different companies contributed to the effort".

Bypassing the NASA hierarchy, he sent a series of memos and reports on the issue to Associate Administrator Robert Seamans; while acknowledging that he spoke "somewhat as a voice in the wilderness", Houbolt pleaded that LOR should not be discounted in studies of the question.

Seamans's establishment of an ad hoc committee headed by his special technical assistant Nicholas E. Golovin in July 1961, to recommend a launch vehicle to be used in the Apollo program, represented a turning point in NASA's mission mode decision.

[44] The engineers at Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), who were heavily invested in direct ascent, took longer to become convinced of its merits, but their conversion was announced by Wernher von Braun at a briefing on June 7, 1962.

[48] Space historian James Hansen concludes that: Without NASA's adoption of this stubbornly held minority opinion in 1962, the United States may still have reached the Moon, but almost certainly it would not have been accomplished by the end of the 1960s, President Kennedy's target date.

[52] The command module (CM) was the conical crew cabin, designed to carry three astronauts from launch to lunar orbit and back to an Earth ocean landing.

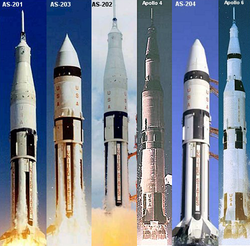

The 22,500-pound (10,200 kg) payload capacity[63] would have severely limited the systems which could be included, so the decision was made in October 1963 to use the uprated Saturn IB for all crewed Earth orbital flights.

The second stage replaced the S-IV with the S-IVB-200, powered by a single J-2 engine burning liquid hydrogen fuel with LOX, to produce 200,000 pounds-force (890 kN) of thrust.

[68] NASA's director of flight crew operations during the Apollo program was Donald K. "Deke" Slayton, one of the original Mercury Seven astronauts who was medically grounded in September 1962 due to a heart murmur.

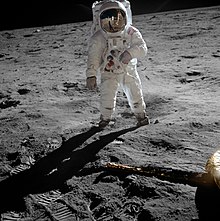

The traditional visor helmet was replaced with a clear "fishbowl" type for greater visibility, and the lunar surface EVA suit would include a water-cooled undergarment.

While the determination of responsibility for the accident was complex, the review board concluded that "deficiencies existed in command module design, workmanship and quality control".

[94] To remedy the causes of the fire, changes were made in the Block II spacecraft and operational procedures, the most important of which were use of a nitrogen/oxygen mixture instead of pure oxygen before and during launch, and removal of flammable cabin and space suit materials.

The Soviet Union had sent two tortoises, mealworms, wine flies, and other lifeforms around the Moon on September 15, 1968, aboard Zond 5, and it was believed they might soon repeat the feat with human cosmonauts.

The command module pilot was Gemini veteran Richard F. Gordon Jr. Conrad and Bean carried the first lunar surface color television camera, but it was damaged when accidentally pointed into the Sun.

Shortly after Apollo 11, NASA publicized a preliminary list of eight more planned landing sites after Apollo 12, with plans to increase the mass of the CSM and LM for the last five missions, along with the payload capacity of the Saturn V. These final missions would combine the I and J types in the 1967 list, allowing the CMP to operate a package of lunar orbital sensors and cameras while his companions were on the surface, and allowing them to stay on the Moon for over three days.

[152] Apollo stimulated many areas of technology, leading to over 1,800 spinoff products as of 2015, including advances in the development of cordless power tools, fireproof materials, heart monitors, solar panels, digital imaging, and the use of liquid methane as fuel.

[153][154][155] The flight computer design used in both the lunar and command modules was, along with the Polaris and Minuteman missile systems, the driving force behind early research into integrated circuits (ICs).

While the Navy and Air Force could work around reliability problems by deploying more missiles, the political and financial cost of failure of an Apollo mission was unacceptably high.