Meridiani Planum

[3][4][5] Each name reflects the coincidental (somewhat arbitrary) fact that the plain straddles the prime meridian for the system of longitude lines introduced for east/west Mars mapping.

Except for transport by large meteor impact, loose surface spherules tend to remain within a few meters of their starting embedded location.

The Meridiani Planum was first observed as part of a larger region that appeared as a distinct dark (low albedo) spot in small telescope images of Mars.

Edgett and Parker[13] noted the smooth terrain of what we now call the Meridiani Planum and realized early that the plain was likely made of sediments and probably had a wet, watery past.

[14] The "Water Strategy" was "to explore and study Mars in three areas: - Evidence of past or present life, - Climate (weather, processes, and history), - Resources (environment and utilization)."

An important survey carried out between 1997 and 2002 by the Mars Global Surveyor collected surface hematite levels with the satellite's thermal emissions spectrometer (TES).

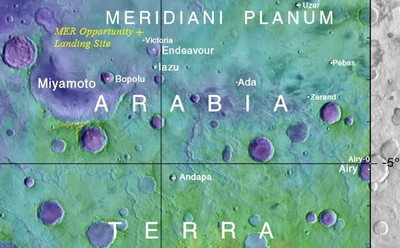

In early the 2000s, the hematite map of Figure 1b and the confirmation (from the topography mapping done by the Mars Global Surveyor) that this area is a flat plain and relatively easy to land on were the decisive pieces of evidence for choosing the Meridiani Planum as one of the landing sites for NASA's two bigger Mars Exploration Rovers (MERs), named Opportunity and Spirit.

[16][18] Since 2001, evidence for water at the present-day Meridiani Planum was collected by the High Energy Neutron Detector (HEND) mounted on the Mars Odyssey orbiter.

[21] The WEH maps are likely to underestimate the present-day water resources at Meridiani Planum since (a) the HEND has a shallow (1 m) penetration depth,[22] (b) the majority of the plain's surface is covered in dehydrated soils, and hematite spherules.

[7][23][24] Starting with Daniel S. Goldin's strategies and NASA's engineering attention to detail, Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity successfully made the "hole-in-one" landing into Eagle Crater at Meridiani Planum on January 24 (PST), 2004.

The dominant visual impressions at eye level are that: This section covers the composition of the major materials found at the Meridiani plain (i.e., sediments, spherules, soils, and dust).

The layered sedimentary outcrop rocks exposed in Eagle, Fram, and Endurance caters were examined by the suite of instruments on Opportunity.

They also observed a hyper-hydrated magnesium sulfate on Earth that they called meridianiite (after Meridiani Planum), with the formula MgSO4.11H2O, which decomposes to epsomite, MgSO4.7H2O, and water at 2 oC.

A 2008 paper published the result of a clever experiment that showed Opportunity's mini-TES (thermal emission spectrometer) could not detect any silicate minerals in the spherules.

Most of the underlying soil consists of basaltic material but mixed with varying amounts of dust and sulfate-rich ejecta debris from the sediments.

On the other hand, a small amount of hematite that was present meant that there may have been liquid water for a short time in the early history of the planet.

[65][43][66] Opportunity studied nine cobbles in the "Arkansas Group" that were breccias displaying evidence of material melting from heat generated by meteorite impacts.

[13] However, they are easy to see in thermal inertia images taken in orbit by Mars Odyssey and reproduced in Figure 13 (click on it for higher resolution).

[40] The change certainly included aqueous geochemistry that was acidic and salty, as well as rising & falling water levels: Features providing evidence include cross-bedded sediments, the presence of vugs (cavities), and embedded hematite spherules that cut across sediment layers, additionally the presence of large amounts of magnesium sulfate and other sulfate-rich minerals such as jarosite and chlorides.

[38] Figure 14 illustrates the four physical constituents of sediment outcrop: (i) the sedimentary layers containing a lot of basaltic sand particles; (ii) the embedded hematite spherules; (iii) fine-grained, sulfate-rich cement (in most parts of the outcrop); (iv) vug cavities (that are thought to be molds for crystals of, for example, hydrated sulfates).

Such abrasions showed that (a) the sediment layers are very soft and easy to cut, and (b) the hematite spherules have uniform internal structures.

[38][37][54][75] The "diagenetic" transformation (i.e., change by water-rock interactions) to today's sediments involved a significant shift in water flows in the region.

Over the hard-to-grasp eon of around three billion years, meteorite impacts, and the wind formed the sandy topsoil and loose hematite spherules and sorted these into the layered soil bedforms that Opportunity's Pancam photographed, and we can now see.

[23][24][7][81] Christensen's rapid assessment of the erosional processes was probably connected to his correct 2000 prediction that the plain's surface material is soft and easy-to-erode (friable).

[2] And that prediction was made after orbiter data showed that Meridiani Planum is very smooth and that small craters degrade and disappear more rapidly than in adjoining regions.

The wide view Figure 3 also shows crest ripples as the sinuous wind-formed lines on top of the smooth sandy soil bedforms.

However, the reader can sense how mind-boggling big those numbers are with a photograph of an area of soil with a typical surface density of the hematite spheres.

The parts of the plain Opportunity studied are not special: Compared to the rest of Meridiani Planum, they do not have high surface hematite levels.

Major Lines of Evidence for Water: The orbiting satellite evidence includes (A) the TES spectra for surface hematite (mapped in Figure 1b) since hematite only forms in watery conditions,[2][5] and (B) the orbiting neutron detector's finding of fairly high levels of WEH over the plain and the adjacent regions (to the west, north, and east).

[38][82][84] The geochemical details of plain's sediments provide more lines of evidence for water, including the presence of large amounts of magnesium sulfate and other sulfate-rich minerals such as jarosite as well as chlorides.