Metallic hydrogen

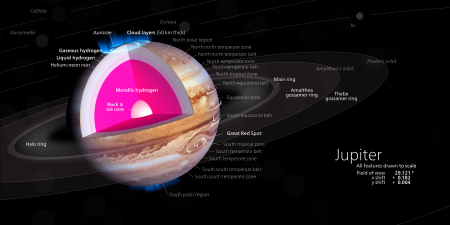

[1] At high pressure and temperatures, metallic hydrogen can exist as a partial liquid rather than a solid, and researchers think it might be present in large quantities in the hot and gravitationally compressed interiors of Jupiter and Saturn, as well as in some exoplanets.

[4] Since the first work by Wigner and Huntington, the more modern theoretical calculations point toward higher but potentially achievable metalization pressures of around 400 GPa (3,900,000 atm; 58,000,000 psi).

In March 1996, a group of scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory reported that they had serendipitously produced the first identifiably metallic hydrogen[22] for about a microsecond at temperatures of thousands of kelvins, pressures of over 100 GPa (1,000,000 atm; 15,000,000 psi), and densities of approximately 0.6 g/cm3.

Previous studies in which solid hydrogen was compressed inside diamond anvils to pressures of up to 250 GPa (2,500,000 atm; 37,000,000 psi), did not confirm detectable metallization.

The scientists found that, as pressure rose to 140 GPa (1,400,000 atm; 21,000,000 psi), the electronic energy band gap, a measure of electrical resistance, fell to almost zero.

Arthur Ruoff and Chandrabhas Narayana from Cornell University in 1998,[24] and later Paul Loubeyre and René LeToullec from Commissariat à l'Énergie Atomique, France in 2002, have shown that at pressures close to those at the center of the Earth (320–340 GPa or 3,200,000–3,400,000 atm) and temperatures of 100–300 K (−173–27 °C), hydrogen is still not a true alkali metal, because of the non-zero band gap.

[27] The theoretically predicted maximum of the melting curve (the prerequisite for the liquid metallic hydrogen) was discovered by Shanti Deemyad and Isaac F. Silvera by using pulsed laser heating.

[30][31] In 2011 Eremets and Troyan reported observing the liquid metallic state of hydrogen and deuterium at static pressures of 260–300 GPa (2,600,000–3,000,000 atm).

[36][37] On 5 October 2016, Ranga Dias and Isaac F. Silvera of Harvard University released claims in a pre-print manuscript of experimental evidence that solid metallic hydrogen had been synthesized in the laboratory at a pressure of around 495 gigapascals (4,890,000 atm; 71,800,000 psi) using a diamond anvil cell.

[38][39][40] In the preprint version of the paper, Dias and Silvera write: With increasing pressure we observe changes in the sample, going from transparent, to black, to a reflective metal, the latter studied at a pressure of 495 GPa... the reflectance using a Drude free electron model to determine the plasma frequency of 30.1 eV at T = 5.5 K, with a corresponding electron carrier density of 6.7×1023 particles/cm3, consistent with theoretical estimates.

[42] In August 2018, scientists announced new observations[43] regarding the rapid transformation of fluid deuterium from an insulating to a metallic form below 2000 K. Remarkable agreement is found between the experimental data and the predictions based on quantum Monte Carlo simulations, which is expected to be the most accurate method to date.