Diamond anvil cell

A diamond anvil cell (DAC) is a high-pressure device used in geology, engineering, and materials science experiments.

[1][2] The device has been used to recreate the pressure existing deep inside planets to synthesize materials and phases not observed under normal ambient conditions.

Common pressure standards include ruby fluorescence,[7] and various structurally simple metals, such as copper or platinum.

In this way, X-ray diffraction and fluorescence; optical absorption and photoluminescence; Mössbauer, Raman and Brillouin scattering; positron annihilation and other signals can be measured from materials under high pressure.

[9] The operation of the diamond anvil cell relies on a simple principle: where p is the pressure, F the applied force, and A the area.

Diamond is a very hard and virtually incompressible material, thus minimising the deformation and failure of the anvils that apply the force.

Percy Williams Bridgman, the great pioneer of high-pressure research during the first half of the 20th century, revolutionized the field of high pressures with his development of an opposed anvil device with small flat areas that were pressed one against the other with a lever-arm.

With just the use of an optical microscope, phase boundaries, color changes and recrystallization could be seen immediately, while x-ray diffraction or spectroscopy required time to expose and develop photographic film.

The diamond cell was created at the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) by Charles E. Weir, Ellis R. Lippincott, and Elmer N.

Van Valkenburg focused on making visual observations, Weir on XRD, Lippincott on IR Spectroscopy.

This cupping phenomenon is the elastic stretching of the edges of the diamond culet, commonly referred to as the "shoulder height".

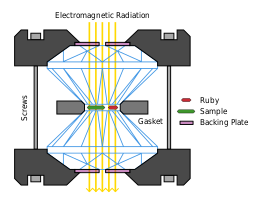

[16] There are many different DAC designs but all have four main components: Relies on the operation of either a lever arm, tightening screws, or pneumatic or hydraulic pressure applied to a membrane.

Made of high gem quality, flawless diamonds, usually with 16 facets, they typically weigh 1⁄8 to 1⁄3 carat (25 to 70 mg).

The culets of the two diamonds face one another, and must be perfectly parallel in order to produce uniform pressure and to prevent dangerous strains.

Hydrostatic pressure is preferred for high-pressure experiments because variation in strain throughout the sample can lead to distorted observations of different behaviors.

The two main pressure scales used in static high-pressure experiments are X-ray diffraction of a material with a known equation of state and measuring the shift in ruby fluorescence lines.

It was found that the wavelength of ruby fluorescence emissions change with pressure; this was easily calibrated against the NaCl scale.

Shock-wave data for the compressibilities of Cu, Mo, Pd, and Ag were available at this time and could be used to define equations of states up to Mbar pressure.

In addition to being hard, diamonds have the advantage of being transparent to a wide range of the electromagnetic spectrum from infrared to gamma rays, with the exception of the far ultraviolet and soft X-rays.

If the cells survived the squeezing and were capable of carrying out life processes, specifically breaking down formate, the dye would turn clear.

Art Yayanos, an oceanographer at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, believes an organism should only be considered living if it can reproduce.

There is practically no debate whether microbial life can survive pressures up to 600 MPa, which has been shown over the last decade or so to be valid through a number of scattered publications.

[26] Similar tests were performed with a low-pressure (0.1–600 MPa) diamond anvil cell, which has better imaging quality and signal collection.

[27] Good single crystal X-ray diffraction experiments in diamond anvil cells require sample stage to rotate on the vertical axis, omega.

The first cell to be used for single crystal experiments was designed by a graduate student at the University of Rochester, Leo Merrill.

The complementary method does not change the temperature of the anvils and includes fine resistive heaters placed within the sample chamber and laser heating.

A tungsten ring-wire resistive heater inside a BX90 DAC filled with Ar gas was reported to reach 1400 °C.

In order for a double-sided heating system to be successful it is essential that the two lasers are aligned so that they are both focused on the sample position.

Noble gases, such as helium, neon, and argon are optically transparent, thermally insulating, have small X-ray scattering factors, and have good hydrostaticity at high pressures.

Once the vessel is filled and the desired pressure is reached the DAC is closed with a clamp system run by motor driven screws.