Metamorphoses

The poem chronicles the history of the world from its creation to the deification of Julius Caesar in a mythico-historical framework comprising over 250 myths, 15 books, and 11,995 lines.

[4] In that tradition myth functioned as a vehicle for moral reflection or insight, yet Ovid approached it as an "object of play and artful manipulation".

The Metamorphoses was longer than any previous collection of metamorphosis myths (Nicander's work consisted of probably four or five books)[6] and positioned itself within a historical framework.

[8] In the case of an oft-used myth such as that of Io in Book I, which was the subject of literary adaptation as early as the 5th century BCE, and as recently as a generation prior to his own, Ovid reorganises and innovates existing material in order to foreground his favoured topics and to embody the key themes of the Metamorphoses.

[15] However, the poem "handles the themes and employs the tone of virtually every species of literature",[16] ranging from epic and elegy to tragedy and pastoral.

[13] The Metamorphoses is comprehensive in its chronology, recounting the creation of the world to the death of Julius Caesar, which had occurred only a year before Ovid's birth;[12] it has been compared to works of universal history, which became important in the 1st century BCE.

[19] The ending acts as a declaration that everything except his poetry—even Rome—must give way to change:[20] And now, my work is done, which neither Jove Nor flame nor sword nor gnawing time can fade.

That day, which governs only my poor frame, May come at will to end my unfixed life, But in my better and immortal part I shall be borne beyond the lofty stars And never will my name be washed away.

Scholar Stephen M. Wheeler notes that "metamorphosis, mutability, love, violence, artistry, and power are just some of the unifying themes that critics have proposed over the years".

[23] In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas / corpora;Metamorphosis or transformation is a unifying theme amongst the episodes of the Metamorphoses.

Ovid raises its significance explicitly in the opening lines of the poem: In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas / corpora; ("I intend to speak of forms changed into new entities;").

[30] No work from classical antiquity, either Greek or Roman, has exerted such a continuing and decisive influence on European literature as Ovid's Metamorphoses.

The emergence of French, English, and Italian national literatures in the late Middle Ages simply cannot be fully understood without taking into account the effect of this extraordinary poem. ...

The only rival we have in our tradition which we can find to match the pervasiveness of the literary influence of the Metamorphoses is perhaps (and I stress perhaps) the Old Testament and the works of Shakespeare.

[40] Among other English writers for whom the Metamorphoses was an inspiration are John Milton—who made use of it in Paradise Lost, considered his magnum opus, and evidently knew it well[35][41]—and Edmund Spenser.

The Metamorphoses was the greatest source of these narratives, such that the term "Ovidian" in this context is synonymous for mythological, in spite of some frequently represented myths not being found in the work.

[51] Other famous works inspired by the Metamorphoses include Pieter Brueghel's painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus and Gian Lorenzo Bernini's sculpture Apollo and Daphne.

[35] The Metamorphoses also permeated the theory of art during the Renaissance and the Baroque style, with its idea of transformation and the relation of the myths of Pygmalion and Narcissus to the role of the artist.

[58] A series of works inspired by Ovid's book through the tragedy of Diana and Actaeon have been produced by French-based collective LFKs and his film/theatre director, writer and visual artist Jean-Michel Bruyere, including the interactive 360° audiovisual installation Si poteris narrare, licet ("if you are able to speak of it, then you may do so") in 2002, 600 shorts and "medium" film from which 22,000 sequences have been used in the 3D 360° audiovisual installation La Dispersion du Fils[59] from 2008 to 2016 as well as an outdoor performance, "Une Brutalité pastorale" (2000).

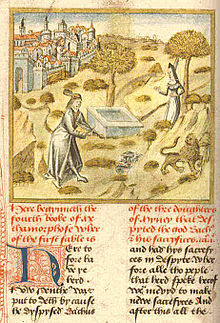

In spite of the Metamorphoses' enduring popularity from its first publication (around the time of Ovid's exile in 8 AD) no manuscript survives from antiquity.

[62] The poem retained its popularity throughout late antiquity and the Middle Ages, and is represented by an extremely high number of surviving manuscripts (more than 400);[63] the earliest of these are three fragmentary copies containing portions of Books 1–3, dating to the 9th century.

[66] Collaborative editorial effort has been investigating the various manuscripts of the Metamorphoses, some forty-five complete texts or substantial fragments,[67] all deriving from a Gallic archetype.

[77] Translation of the Metamorphoses after this period was comparatively limited in its achievement; the Garth volume continued to be printed into the 1800s, and had "no real rivals throughout the nineteenth century".

[80] In 1994, a collection of translations and responses to the poem, entitled After Ovid: New Metamorphoses, was produced by numerous contributors in emulation of the process of the Garth volume.

[86] The format is emblematic of the collaboration between Tournes and Salomon, which has existed since their association in the mid-1540s: the pages are developed centred around a title, an engraving with an octosyllabic stanza and a neat border.

In 1546, Jean de Tournes published a first, non-illustrated version of the first two books of the Metamorphoses, for which Bernard Salomon prepared twenty-two initial engravings.