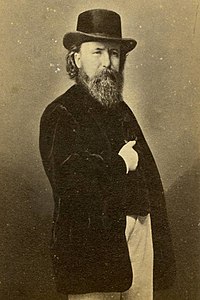

Michael Doheny

He would continue his formal education into his adult life while simultaneously acting as a teacher himself to local children.

Doheny's ambition was to receive a formal legal education so that he could become a lawyer capable of seeking redress for members of his community, who were generally poor.

This allowed him to successfully prosecute former borough officers for corruption, including misappropriation of funds and fraudulent transfers of property, which won Doheny wider acclaim.

[2] It was suggested by historians James Quinn and Desmond McCabe that Doheny may have been a better orator than a writer, and that he excelled more so during public meetings of the repeal movement around Tipperary and in Dublin.

Doheny would later claim that, alongside Thomas Davis and John Blake Dillon, he deliberately ran repeal meetings with military undertones in order to prepare the Irish peasantry for a future war with the British.

Tensions continued to mount between the two when O'Connell took offence to Doheny's view that university education in Ireland should be of a secular/non-denominational nature during public debates over the Maynooth College Act 1845.

[3] In April 1846, William Smith O'Brien was imprisoned for a month for refusing to serve on a parliamentary committee.

Doheny attempted to raise men in Tipperary, but his efforts were held back by William Smith O'Brien's indecisiveness.

Doheny eventually escaped Ireland by dressing as a priest and boarding a cattle ship travelling from Cork to Bristol.

However, he remained active in Irish Republican circles, which were common in the city as it swelled with other Young Irelander exiles.

There were tensions amongst the conservative and radical Young Irelanders in New York, exemplified by an incident involving Doheny and Thomas D'Arcy McGee.

Historians James Quinn and Desmond McCabe note that John Blake Dillon made similar accusations against Doheny, and therefore they may not have been without foundation.

[3] In 1849, Doheny wrote the book The Felon's track, which recounted in a very critical way the history of the repeal movement and the 1848 rebellion.

[2] In February 1856, Doheny and O'Mahony founded the Emmet Monument Association, an organisation with the publicly stated goal of funding a monument to Irish rebel leader Robert Emmet, but with the private goal of unifying Irish Republicans in America under one banner.

The failure to secure the backing of the Russians is suggested to have demoralised many of the Irish-American organisations, causing some of them to fall apart.

[2] Doheny was involved in the funeral arrangements for Terence Bellew MacManus in Ireland and acted as one of his pallbearers in a New York ceremony.

Doheny's morale was high for the enthusiasm he saw that he began to argue again for another rebellion in Ireland, but this line of thinking was overruled by James Stephens.

[2][3] Doheny is best known as author of a small work, The Felon's Track, (Text at Project Gutenberg) New York, 1867, and of two poems, "Achusha gal machree" and "The Outlaw's Wife."