Microbial fuel cell

The first MFCs, demonstrated in the early 20th century, used a mediator: a chemical that transfers electrons from the bacteria in the cell to the anode.

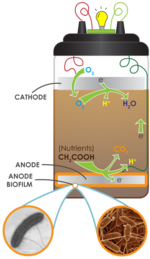

Unmediated MFCs emerged in the 1970s; in this type of MFC the bacteria typically have electrochemically active redox proteins such as cytochromes on their outer membrane that can transfer electrons directly to the anode.

In 1931, Barnett Cohen created microbial half fuel cells that, when connected in series, were capable of producing over 35 volts with only a current of 2 milliamps.

MFCs operate well in mild conditions, 20 °C to 40 °C and at pH of around 7[30] but lack the stability required for long-term medical applications such as in pacemakers.

[31] Soil-based microbial fuel cells serve as educational tools, as they encompass multiple scientific disciplines (microbiology, geochemistry, electrical engineering, etc.)

[clarification needed] BOD values are determined by incubating samples for 5 days with proper source of microbes, usually activated sludge collected from wastewater plants.

Oxygen and nitrate are interfering preferred electron acceptors over the anode, reducing current generation from an MFC.

This can be avoided by inhibiting aerobic and nitrate respiration in the MFC using terminal oxidase inhibitors such as cyanide and azide.

[38] In 2010, A. ter Heijne et al.[39] constructed a device capable of producing electricity and reducing Cu2+ ions to copper metal.

Mediator-free microbial fuel cells use electrochemically active bacteria such as Shewanella putrefaciens[45] and Aeromonas hydrophila[46] to transfer electrons directly from the bacterial respiratory enzyme to the electrode.

While MFCs produce electric current by the bacterial decomposition of organic compounds in water, MECs partially reverse the process to generate hydrogen or methane by applying a voltage to bacteria.

This supplements the voltage generated by the microbial decomposition of organics, leading to the electrolysis of water or methane production.

[50][51] A complete reversal of the MFC principle is found in microbial electrosynthesis, in which carbon dioxide is reduced by bacteria using an external electric current to form multi-carbon organic compounds.

[52] Soil-based microbial fuel cells adhere to the basic MFC principles, whereby soil acts as the nutrient-rich anodic media, the inoculum and the proton exchange membrane (PEM).

Soils naturally teem with diverse microbes, including electrogenic bacteria needed for MFCs, and are full of complex sugars and other nutrients that have accumulated from plant and animal material decay.

Furthermore, the biological process from which the energy is obtained simultaneously purifies residual water for its discharge in the environment or reuse in agricultural/industrial uses.

[57] The sub-category of phototrophic MFCs that use purely oxygenic photosynthetic material at the anode are sometimes called biological photovoltaic systems.

Porous membranes allow passive diffusion thereby reducing the necessary power supplied to the MFC in order to keep the PEM active and increasing the total energy output.

This mixture is placed in a sealed chamber to prevent oxygen from entering, thus forcing the micro-organism to undertake anaerobic respiration.

As with the electron chain in the yeast cell, this could be a variety of molecules such as oxygen, although a more convenient option is a solid oxidizing agent, which requires less volume.

[69] Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) have emerged as promising tools for environmental remediation due to their unique ability to utilize the metabolic activities of microorganisms for both electricity generation and pollutant degradation.

Moreover, MFCs play a significant role in wastewater treatment by simultaneously generating electricity and enhancing water quality through the microbial degradation of contaminants.

The applications of microbial fuel cells in environmental remediation highlight their potential to convert pollutants into a renewable energy source while actively contributing to the restoration and preservation of ecosystems.

Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) offer significant potential as sustainable and innovative technologies, but they are not without their challenges.

One major obstacle lies in the optimization of MFC performance, which remains a complex task due to various factors including microbial diversity, electrode materials, and reactor design.

[72] The development of cost-effective and long-lasting electrode materials presents another hurdle, as it directly affects the economic viability of MFCs on a larger scale.

Nonetheless, ongoing research in microbial fuel cell technology continues to address these obstacles.

Scientists are actively exploring new electrode materials, enhancing microbial communities to improve efficiency, and optimizing reactor configurations.

Moreover, advancements in synthetic biology and genetic engineering have opened up possibilities for designing custom microbes with enhanced electron transfer capabilities, pushing the boundaries of MFC performance.

[73] Collaborative efforts between multidisciplinary fields are also contributing to a deeper understanding of MFC mechanisms and expanding their potential applications in areas such as wastewater treatment, environmental remediation, and sustainable energy production.