Medieval Latin

It was also the administrative language in the former Roman Provinces of Mauretania, Numidia and Africa Proconsularis under the Vandals, the Byzantines and the Romano-Berber Kingdoms, until it declined after the Arab Conquest.

Medieval Latin in Southern and Central Visigothic Hispania, conquered by the Arabs immediately after North Africa, experienced a similar fate, only recovering its importance after the Reconquista by the Northern Christian Kingdoms.

Germanic leaders became the rulers of parts of the Roman Empire that they conquered, and words from their languages were freely imported into the vocabulary of law.

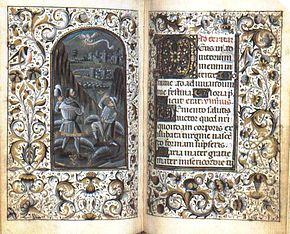

The high point of the development of Medieval Latin as a literary language came with the Carolingian Renaissance, a rebirth of learning kindled under the patronage of Charlemagne, king of the Franks.

This was especially true beginning around the 12th century, after which the language became increasingly adulterated: late Medieval Latin documents written by French speakers tend to show similarities to medieval French grammar and vocabulary; those written by Germans tend to show similarities to German, etc.

Many of these developments are similar to Standard Average European and the use of medieval Latin among the learned elites of Christendom may have played a role in the spread of those features.

In every age from the late 8th century onwards, there were learned writers (especially within the Church) who were familiar enough with classical syntax to be aware that these forms and usages were "wrong" and resisted their use.

Thus the Latin of a theologian like St Thomas Aquinas or of an erudite clerical historian such as William of Tyre tends to avoid most of the characteristics described above, showing its period in vocabulary and spelling alone; the features listed are much more prominent in the language of lawyers (e.g. the 11th-century English Domesday Book), physicians, technical writers and secular chroniclers.

[4] There are many prose constructions written by authors of this period that can be considered "showing off" a knowledge of Classical or Old Latin by the use of rare or archaic forms and sequences.

Though they had not existed together historically, it is common that an author would use grammatical ideas of the two periods Republican and archaic, placing them equally in the same sentence.

The first half of the 5th century saw the literary activities of the great Christian authors Jerome (c. 347–420) and Augustine of Hippo (354–430), whose texts had an enormous influence on theological thought of the Middle Ages, and of the latter's disciple Prosper of Aquitaine (c. 390 – c. 455).

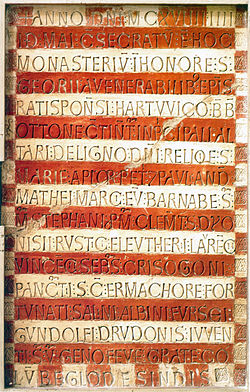

This was also a period of transmission: the Roman patrician Boethius (c. 480–524) translated part of Aristotle's logical corpus, thus preserving it for the Latin West, and wrote the influential literary and philosophical treatise De consolatione Philosophiae; Cassiodorus (c. 485 – c. 585) founded an important library at the monastery of Vivarium near Squillace where many texts from Antiquity were to be preserved.

At the same time, good knowledge of Latin and even of Greek was being preserved in monastic culture in Ireland and was brought to England and the European mainland by missionaries in the course of the 6th and 7th centuries, such as Columbanus (543–615), who founded the monastery of Bobbio in Northern Italy.

Benedict Biscop (c. 628–690) founded the monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow and furnished it with books which he had taken home from a journey to Rome and which were later used by Bede (c. 672–735) to write his Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

Long-distance communication in the vernacular was rare, but Hebrew, Arabic and Greek served a similar purpose among Jews, Muslims and Eastern Orthodox respectively.