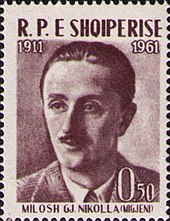

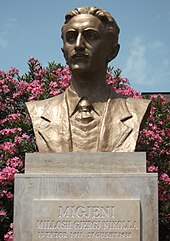

Migjeni

He wrote about the poverty of the years he lived in, with writings such as "Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread", "The Killing Beauty", "Forbidden Apple", "The Corn Legend", "Would You Like Some Charcoal?"

The proliferation of his creativity gained a special momentum after World War II, when the communist regime took over the full publication of works, which in the 1930s had been partially unpublished.

[2][1] His surname derived from his grandfather Nikolla, who hailed from the region of Upper Reka from where he moved to Shkodër in the late 19th century where he practiced the trade of a bricklayer and later married Stake Milani from Kuči, Montenegro, with whom he had two sons: Gjergj (Migjeni's father) and Kristo.

[12] At 14 years of age, in autumn 1925, he received a scholarship to attend secondary school in Monastir (Bitola) (also in former Yugoslavia),[12] from where he graduated in 1927,[13] then entered the Orthodox seminary of St. John the Theologian.

[15] In May 1934, his first short prose piece, Sokrat i vuejtun apo derr i kënaqun (Suffering Socrates or a satisfied pig), was published in the periodical Illyria,[16] under his new pen name Migjeni, an acronym of Millosh Gjergj Nikolla.

[17] He journeyed to Athens, Greece in July of that year in hope of obtaining treatment for the disease which was endemic on the marshy coastal plains of Albania at the time but returned to Shkodra a month later with no improvement in his condition.

Migjeni later received the transfer he had earlier requested to the mountain village of Puka and in April 1936 began his activities as the headmaster of the run-down school there.

After eighteen difficult months in the mountains, he was obliged to put an end to his career in order to seek medical treatment in Turin in Northern Italy where his sister Ollga was studying mathematics.

We show our consolation only in tears... Our inheritance from all these years is misery... because within the womb of the Universe our world is a tomb, where mankind are condemned to sneak like snakes, and their will as if squeezed in the fist of a giant breaks.

- One eye glittering with distilled drops of the deepest pain glimmers from far across the vale of tears, and sometimes an instinctive pulse of frustrated thought flashes out across the spheres seeking an outlet for anger overwrought.

And each such man must take his fate in his own hands, hoping for the smallest victory, and seek out distant lands; where all the roads are laid with thorns and on every side walled in by gravestones all besmeared with tears and lunatics who, silent, grin.

Previous generations of poets had sung the beauties of the Albanian mountains and the sacred traditions of the nation, whereas Migjeni now opened his eyes to the harsh realities of life, to the appalling level of misery, disease, and poverty he discovered all around him.

Typical of the suffering and of the futility of human endeavor for Migjeni is Rezignata ("Resignation"), a poem in the longest cycle of the collection, Kangët e mjerimit ("Songs of poverty").

[citation needed] He was a product of the 1930s, an age in which Albanian intellectuals, including Migjeni, were particularly fascinated by the West and in which, in Western Europe itself, the rival ideologies of communism and fascism were colliding for the first time in the Spanish Civil War.

To a Trotskyist friend, André Stefi, who had warned him that the communists would not forgive for such poems, Migjeni replied, "My work has a combative character, but for practical reasons, and taking into account our particular conditions, I must maneuver in disguise.

Migjeni's religious education and his training for the Orthodox priesthood seem to have been entirely counterproductive, for he cherished neither an attachment to religion nor any particularly fond sentiments for the organized Church.

[citation needed] In Kanga skandaloze ("Scandalous song"), Migjeni expresses a morbid attraction to a pale nun and at the same time his defiance and rejection of her world.

Passion and rapturous desire are ubiquitous in his verse, but equally present is the specter of physical intimacy portrayed in terms of disgust and sorrow.

[citation needed] Regarding his legacy, Elsie writes: "Though Migjeni did not publish a single book during his lifetime, his works, which circulated privately and in the press of the period, were an immediate success.

The question remains highly hypothetical, for this individualist voice of genuine social protest would no doubt have suffered the same fate as most Albanian writers of talent in the late 1940s, i.e. internment, imprisonment or execution.