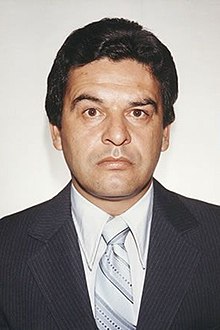

Miguel de la Madrid

[1] Inheriting a severe economic and financial crisis from his predecessor José López Portillo as a result of the international drop in oil prices and a crippling external debt on which Mexico had defaulted months before he took office, De la Madrid introduced sweeping neoliberal policies to overcome the crisis, beginning an era of market-oriented presidents in Mexico, along with austerity measures involving deep cuts in public spending.

In addition, his administration was criticized for its slow response to the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, and the handling of the controversial 1988 elections in which the PRI candidate Carlos Salinas de Gortari was declared winner, amid accusations of electoral fraud.

He was the son of Miguel de la Madrid Castro, a notable lawyer (who was assassinated when the future President was only two),[4] and Alicia Hurtado Oldenbourg.

[9] De la Madrid inherited the financial catastrophe from his predecessor; Mexico experienced per capita negative growth for his entire term.

The end of his administration was even worse, with his choice of Carlos Salinas de Gortari as his successor, the split in the PRI with the exit of Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, and the government's handling of balloting with election results deemed fraudulent.

All that was a stark reminder of the gross mismanagement and policies of his two immediate predecessors, particularly the financing of development with excessive overseas borrowing, which was often countered by high internal capital flights.

[11] De la Madrid himself had been Minister of Budget and Programming under López Portillo, and as such he was perceived by many as being co-responsible for the crisis that he himself had to deal with upon taking office.

[16] In response to these controversies, an electoral reform was conducted in 1986: Since his campaign for the presidency, De la Madrid had mentioned the importance of discussing the topic of abortion, given the high national demographic growth and the scarce resources that the country had to deal with the necessities of an ever-growing population, specially in the middle of the economic crisis.

[21][22] On 1 May 1984, an anti-government activist named José Antonio Palacios Marquina, along with others, threw Molotov cocktails at the balcony of the Presidential Palace, where De la Madrid was reviewing the May Day parade.

On 22 December, the Procuraduría General de Justicia found the state-run oil company Pemex to be responsible for the incident, and was ordered to pay indemnification to the victims.

[2] The federal government's first public response was President de la Madrid's declaration of a period of mourning for three days starting from 20 September 1985.

[28] De la Madrid initially refused to send the military to assist on the rescue efforts, and it was later deployed to patrol streets only to prevent looting after a curfew was imposed.

The crisis was severe enough to have tested the capabilities of wealthier countries, but the government from local PRI bosses to President de la Madrid himself exacerbated the problem aside from the lack of money.

There were some protests against the tournament, as Mexico was going through an economic crisis at the time and the country was still recovering from the 1985 earthquake, therefore the World Cup was considered by many as a lavish and unnecessary expense.

[33] During the World Cup's inauguration at the Estadio Azteca on 31 May, just before the opening match Italy vs Bulgaria, De la Madrid was jeered by a crowd of 100,000 while trying to give a speech,[34] apparently in protest over his administration's poor reaction to the 1985 earthquake.

[35][36][37] An official who was present at the event recalled that "[The President's] words were completely drowned out by boos and whistles [...] I was dying with embarrassment, but it seemed to be the right metaphor for the mood of the country.

When they failed, Cárdenas, Muñoz Ledo and Martínez left the PRI the following year and created the National Democratic Front (Frente Democrático Nacional), a loose alliance of left-wing parties.

In 1983, the Contadora Group was launched by Colombia, Panama, Venezuela and Mexico to promote peace in Latin America and to deal with the armed conflicts in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala.

In the assessment of political scientist Roderic Ai Camp, "It would be fair to say that the election of Carlos Salinas de Gortari in 1988 marked the low point of that office as well as the declining legitimacy of the state.

On one hand, after he and Muñoz Ledo were expelled from the PRI, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas was nominated presidential candidate by the Frente Democrático Nacional, a coalition of leftist parties.

Cárdenas attained massive popularity as result of his efforts at democratizing the PRI, his successful tenure as Governor of Michoacán, his opposition to the austerity reforms and his association with his father's nationalist policies.

Surrounded by garden and offices, it hosts cultural unity Jesús Silva Herzog, the Gonzalo Robles Library, which houses the growing publishing history of the Fund, and the seller Alfonso Reyes.

This Thus, the FCE reached a significant presence in Latin America with nine subsidiaries: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Spain, United States, Guatemala, Peru and Venezuela.

In publishing field, under his direction, 21 new collections were launched: in 1990, Keys (Argentina) in 1991, A la Orilla del Viento, Mexican Codices, University Science and Special Editions of At the Edge of the wind; in 1992, Breviary of Contemporary Science (Argentina) and New Economic Culture, in 1993 Library Prospective, Mexican Library, Library Cervantes Prize (Spain), and History of the Americas Trust and Cruises, in 1994, Word of Life and Indians A Vision of America and the Modernization of Mexico; Files, Sunstone (Peru), Entre Voces, Reading and Designated Fund 2000; Encounters (Peru) History of Mexico, and five periodicals: Galeras Fund, Periolibros, Images, Spaces for Reading and the Fund page.

As a result, on the same day De la Madrid issued a statement retracting the comments he had made during the interview with Aristegui, claiming that due to his advanced age and his poor health, he was not able to "correctly process" the questions.

[55] Unlike his predecessors (specially Luis Echeverría and José López Portillo), President De la Madrid was noted for making relatively few speeches and keeping a more reserved and moderate public image.

Although that has been attributed to a strategy to break with his predecessors' populist legacies, President De la Madrid's public image was considered "gray" by critics.

[56] This perception worsened with his government's slow response to the 1985 Earthquake, when President De la Madrid also rejected International aid in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy.

Under his "Moral Renovation" campaign, his administration attempted to fight corruption at all Government levels, fulfilling Mexico's foreign debt compromises, and creating the Secretaría de la Contraloría General de la Federación (Secretariat of the General Inspectorate of the Federation) to guarantee fiscal discipline and to keep an eye on possible corrupt officials.

In a 1998 interview for a documentary produced by Clío TV about his administration, De la Madrid himself concluded: "What hurts me the most, is that those years of economic adjustment and structural change, were also characterized by a deterioration of the income distribution, a depression of the real wages, and an insufficient creation of jobs.