Milgram experiment

Beginning on August 7, 1961, a series of social psychology experiments were conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram, who intended to measure the willingness of study participants to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts conflicting with their personal conscience.

Milgram first described his research in a 1963 article in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology[1] and later discussed his findings in greater depth in his 1974 book, Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View.

[3] The experiments began on August 7, 1961 (after a grant proposal was approved in July), in the basement of Linsly-Chittenden Hall at Yale University, three months after the start of the trial of German Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem.

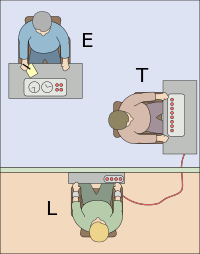

The experimenter told them that they were taking part in "a scientific study of memory and learning", to see what the effect of punishment is on a subject's ability to memorize content.

The experimenter, dressed in a lab coat in order to appear to have more authority, told the participants this was to ensure that the learner would not escape.

As the voltage of the fake shocks increased, the learner began making audible protests, such as banging repeatedly on the wall that separated him from the teacher.

"[1] Before conducting the experiment, Milgram polled fourteen Yale University senior-year psychology majors to predict the behavior of 100 hypothetical teachers.

[1] He also reached out to honorary Harvard University graduate Chaim Homnick, who noted that this experiment would not be concrete evidence of the Nazis' innocence, due to the fact that "poor people are more likely to cooperate".

Milgram also polled forty psychiatrists from a medical school, and they believed that by the tenth shock, when the victim demands to be free, most subjects would stop the experiment.

These signs included sweating, trembling, stuttering, biting their lips, groaning, and digging their fingernails into their skin, and some were even having nervous laughing fits or seizures.

I set up a simple experiment at Yale University to test how much pain an ordinary citizen would inflict on another person simply because he was ordered to by an experimental scientist.

The extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any lengths on the command of an authority constitutes the chief finding of the study and the fact most urgently demanding explanation.

Moreover, even when the destructive effects of their work become patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.

[2][15] The participants who refused to administer the final shocks neither insisted that the experiment be terminated, nor left the room to check the health of the victim as per Milgram's notes.

[17] Milgram’s experiment raised immediate controversy about the research ethics of scientific experimentation because of the extreme emotional stress and inflicted insight suffered by the participants.

On June 10, 1964, the American Psychologist published a brief but influential article by Diana Baumrind titled "Some Thoughts on Ethics of Research: After Reading Milgram's 'Behavioral Study of Obedience.'"

Baumrind's criticisms of the treatment of human participants in Milgram's studies stimulated a thorough revision of the ethical standards of psychological research.

[19] In his 1974 book Obedience to Authority, Milgram described receiving offers of assistance, requests to join his staff, and letters of thanks from former participants.

[22] Milgram sparked direct critical response in the scientific community by claiming that "a common psychological process is centrally involved in both [his laboratory experiments and Nazi Germany] events.

While it may well account for the dutiful destructiveness of the dispassionate bureaucrat who may have shipped Jews to Auschwitz with the same degree of routinization as potatoes to Bremerhaven, it falls short when one tries to apply it to the more zealous, inventive, and hate-driven atrocities that also characterized the Holocaust.

Hence, the underlying cause for the subjects' striking conduct could well be conceptual, and not the alleged 'capacity of man to abandon his humanity ... as he merges his unique personality into larger institutional structures."'

This last explanation receives some support from a 2009 episode of the BBC science documentary series Horizon, which involved replication of the Milgram experiment.

[36][37] Also a neuroscientific study supports this perspective, namely that watching the learner receive electric shocks does not activate brain regions involving empathic concerns.

In Experiment 18, the participant performed a subsidiary task (reading the questions via microphone or recording the learner's answers) with another "teacher" who complied fully.

As reported by Perry in her 2012 book Behind the Shock Machine, some of the participants experienced long-lasting psychological effects, possibly due to the lack of proper debriefing by the experimenter.

[40] In 2002, the British artist Rod Dickinson created The Milgram Re-enactment, an exact reconstruction of parts of the original experiment, including the uniforms, lighting, and rooms used.

A partial replication of the experiment was staged by British illusionist Derren Brown and broadcast on UK's Channel 4 in The Heist (2006).

Burger noted that "current standards for the ethical treatment of participants clearly place Milgram's studies out of bounds."

[44] Burger found obedience rates virtually identical to those reported by Milgram in 1961–62, even while meeting current ethical regulations of informing participants.

[48] Charles Sheridan and Richard King (at the University of Missouri and the University of California, Berkeley, respectively) hypothesized that some of Milgram's subjects may have suspected that the victim was faking, so they repeated the experiment with a real victim: a "cute, fluffy puppy" who was given real, albeit apparently harmless, electric shocks.