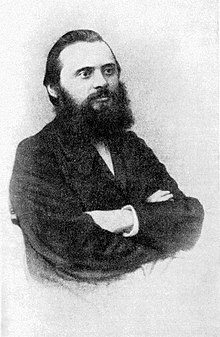

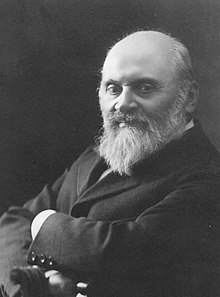

Mily Balakirev

Mily Alexeyevich Balakirev (UK: /bəˈlækɪrɛv, -ˈlɑːk-/ bə-LA(H)K-i-rev, US: /ˌbɑːlɑːˈkɪərɛf/ BAH-lah-KEER-ef; Russian: Милий Алексеевич Балакирев,[note 1] pronounced [ˈmʲilʲɪj ɐlʲɪkˈsʲe(j)ɪvʲɪdʑ bɐˈlakʲɪrʲɪf] ⓘ; 2 January 1837 [O.S.

In conjunction with critic and fellow nationalist Vladimir Stasov, in the late 1850s and early 1860s, Balakirev brought together the composers now known as The Five (a.k.a., The Mighty Handful) – the others were Alexander Borodin, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.

[1][2][3] The legend of a supposed Tatar ancestor who was baptized and took part in the Battle of Kulikovo as Dmitry Donskoy's personal khorunzhyi that circulated among fellow composers was made up by Balakirev and does not find any proof.

His holidays were spent either at Nizhny Novgorod or on the Ulybyshev country estate at Lukino, where he played numerous Beethoven sonatas to help his patron with his book on the composer.

Nevertheless, his time with Glinka had sparked a passion for Russian nationalism within Balakirev, leading him to adopt the stance that Russia should have its own distinct school of music, free from Southern and Western European influences.

[7] Together with Cui, these men were described by noted critic Vladimir Stasov as "a mighty handful" (Russian: Могучая кучка, Moguchaya kuchka), but they eventually became better known in English simply as The Five.

[15] By the late 1860s, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov stopped accepting what they now considered his high-handed meddling with their work,[17] and Stasov began to distance himself from Balakirev.

[18] The formation of The Five paralleled the early years of Tsar Alexander II, a time of innovation and reform in the political and social climate in Russia.

Balakirev's sympathies and closest contacts were in the latter camp, and he frequently made derogatory comments about the German "routine" which, he believed, came at the expense of the composer's originality.

Mussorgsky, for instance, called the Saint Petersburg Conservatory a place where Rubinstein and Nikolai Zaremba, who taught music theory there, dressed "in professional, antimusical togas, first pollute their students' minds, then seal them with various abominations.

These arrangements showed great insight into the rhythm, harmony and types of song, although the key signatures and elaborate textures of the piano accompaniments were not as idiomatic.

[25] Balakirev also intermittently spent time editing Glinka's works for publication, on behalf of the composer's sister, Lyudmilla Shestakova.

[27] Balakirev suspected Smetana and others were influenced by pro-Polish elements of the Czech press, which labeled the production a "Tsarist intrigue" paid for by the Russian government.

[27] He had difficulties with the production of Ruslan and Lyudmila under his direction, with the Czechs initially refusing to pay for the cost of copying the orchestral parts, and the piano reduction of the score, from which Balakirev was conducting rehearsals, mysteriously disappearing.

"[29] Regardless, though A Life for the Tsar and Ruslan and Lyudmila were successes, Balakirev's lack of tact and despotic nature created considerable ill feelings between him and others involved.

[29] During this visit, Balakirev sketched and partly orchestrated an Overture on Czech Themes; this work would be performed at a May 1867 Free School concert given in honor of Slav visitors to the All-Russian Ethnographical Exhibition in Moscow.

The conservative patron for the RMS, Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, agreed—provided Nikolai Zaremba, who had taken over for Rubinstein at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory was also appointed, along with a distinguished foreign composer.

[33] This exchange of letters grew into a friendship and a creative collaboration over the next two years, with Balakirev helping Tchaikovsky produce his first masterpiece, the fantasy-overture Romeo and Juliet.

[35] In the same letter, he forwarded the programme for a symphony, based on Lord Byron's poem Manfred, which Balakirev was convinced Tchaikovsky "would handle wonderfully well."

This rivalry caused financial difficulties for both concert societies as RMS membership declined and the Free Music School continued to suffer from chronic money troubles.

[40] The RMS then scored the coup de grâce of assigning its programming to Mikhaíl Azanchevsky, who also took over as director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in 1871.

[40] For the opening concert of the RMS 1871–72 season, he had conductor Eduard Nápravník present the first public performances of Tchaikovsky's Romeo and Juliet and the polonaise from Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov.

[52] Except initially for Glazunov, whom he brought to Rimsky-Korsakov as a prodigy, and his later acolyte Sergei Lyapunov, Balakirev was ignored by the younger generation of Russian composers.

[57] Following his breakdown, Balakirev sought solace in the strictest sect of Russian Orthodoxy,[40] dating his conversion to the anniversary of his mother's death in March 1871.

Rimsky-Korsakov relates some of Balakirev's extremes in behavior at this point—how he had "given up eating meat, and ate fish, but ... only those which had died, never the killed variety"; how he would remove his hat and quickly cross himself whenever he passed by a church; and how his compassion for animals reached the point that whenever an insect was found in a room, he would carefully catch it and release it from a window, saying, "Go thee, deary, in the Lord, go!

[62] "All this medley of Christian meekness, backbiting, fondness for beasts, misanthropy, artistic interests, and a triviality worthy of an old maid from a hospice, all these struck everyone who saw him in those days", Rimsky-Korsakov wrote, adding that these traits intensified further in subsequent years.

This was because they had been overtaken stylistically by the accomplishments of younger composers, and because some of their compositional devices were appropriated by other members of The Five—the most notable example of the latter is Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade, which was influenced by Balakirev's symphonic poem Tamara.

However, Balakirev advances on Glinka's technique of using "variations with changing backgrounds," reconciling the compositional practices of classical music with the idiomatic treatment of folk song, employing motivic fragmentation, counterpoint and a structure exploiting key relationships.

[72] Balakirev began his First Symphony after completing the Second Overture but cut work short to concentrate on the Overture on Czech Themes, recommencing on the symphony only 30 years later and not finishing it until 1897. Letters from Balakirev to Stasov and Cui indicate that the first movement was two-thirds completed and the final movement sketched out, though he would supply a new theme for the finale many years later.

However, he was inspired by the poetry of Mikhail Lermontov about the seductress Tamara, who waylays travelers in her tower at the Darial Gorge and allows them to savor a night of sensual delights before killing them and flinging their bodies into the Terek River.