Milk allergy

Unlike with IgE reactions, there are no specific biomarker molecules circulating in the blood, and confirmation of the allergy is achieved by removing the suspect food from the diet and determining if symptoms dissipate as a result.

[25] IgE-mediated symptoms include: rash, hives, itching of the mouth, lips, tongue, throat, eyes, skin, or other areas, swelling of the lips, tongue, eyelids, or the whole face, difficulty swallowing, runny or congested nose, hoarse voice, wheezing, shortness of breath, diarrhea, abdominal pain, lightheadedness, fainting, nausea and vomiting.

FPIES can be severe, characterized by persistent vomiting one to four hours after an allergen-containing food is ingested, to the point of lethargy.

Watery and sometimes bloody diarrhea can develop five to ten hours after the triggering meal, to the point of dehydration and low blood pressure.

One theory is that resistance to digestion occurs when largely intact proteins reach the small intestine and the white blood cells involved in immune reactions are activated.

[34][35] In the early stages of acute allergic reaction, lymphocytes previously sensitized to a specific protein or protein fraction react by quickly producing a particular type of antibody known as secreted IgE (sIgE), which circulates in the blood and binds to IgE-specific receptors on the surface of other kinds of immune cells called mast cells and basophils.

[34] Activated mast cells and basophils undergo a process called degranulation, during which they release histamine and other inflammatory chemical mediators (cytokines, interleukins, leukotrienes and prostaglandins) into the surrounding tissue causing several systemic effects, such as vasodilation, mucous secretion, nerve stimulation and smooth-muscle contraction.

Heat can reduce allergenic potential, so dairy ingredients in baked goods may be less likely to trigger a reaction than would milk or cheese.

Some will display both, so that a child could react to an oral food challenge with respiratory symptoms and hives (skin rash), followed a day or two later with a flareup of atopic dermatitis and gastrointestinal symptoms, including chronic diarrhea, blood in the stools, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), constipation, chronic vomiting and colic.

[4] Attempts have been made to identify SPT and IgE responses accurate enough to avoid the need for confirmation with an oral food challenge.

A systematic review stated that in children younger than two years, cutoffs for specific IgE or SPT seem to be more homogeneous and may be proposed.

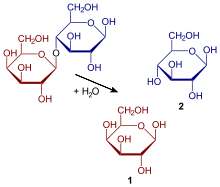

The unabsorbed lactose reaches the large intestine, where resident bacteria use it for fuel, releasing hydrogen, carbon dioxide and methane gases.

Reviews have concluded that no strong evidence exists to recommend changes to the diets of pregnant or nursing women as a means of preventing the development of food allergy in their infants.

[46] There is some evidence that formula supplement given within the first 24 hours of a babies life in hospital increases the incidence of cow's milk allergy for mothers who then go on to exclusively breast feed.

[50] A different consideration occurs when a family history exists, either in parents or older siblings, of milk allergy.

[6] Most patients with milk allergy find it necessary to strictly avoid any item containing dairy ingredients[16] because the threshold dose capable of provoking an allergic reaction can be quite small, especially in infants.

Patients are advised to always carefully read food package labels, as sometimes even a familiar brand undergoes an ingredient change.

[60] In the U.S., for all foods except meat, poultry, egg-processed products and most alcoholic beverages, if an ingredient is derived from one of the required-label allergens, the product's packaging must display the food name in parentheses or include a statement separate from, but adjacent to, the ingredients list that specifically names each allergen.

The second addresses unintentional possible introduction of ingredients occurring during transportation, storage or at the manufacturing site, and is voluntary; this is known as precautionary allergen labeling.

[68] In opposition to this recommendation, a published scientific review stated that there was not yet sufficient evidence in the human trial literature to conclude that maternal dietary food avoidance during lactation would prevent or treat allergic symptoms in breastfed infants.

According to several studies cited in the review, between 10% and 14% of infants and young children with confirmed cow's milk allergy were determined to also be sensitized to soy and in some instances have a clinical reaction after consuming a soy-containing food.

Childhood predictors for adult persistence are anaphylaxis, high milk-specific serum IgE, robust response to the skin prick test and absence of tolerance to milk-containing baked foods.

[3] People with confirmed cow's milk allergy may also demonstrate an allergic response to beef, especially when cooked rare, because of the presence of bovine serum albumin.

For those classified as allergic to cow's milk, mean weight, height and body-mass index were significantly lower than for their non-allergic peers.

"[73] With the passage of mandatory labeling laws, food-allergy awareness has increased, with impacts on the quality of life for children, their parents and their immediate caregivers.

However, labeling laws do not mandate the declaration of the presence of trace amounts in the final product as a consequence of cross-contamination, except in Brazil.

[15][18] FALCPA applies to packaged foods regulated by the FDA, which does not include poultry, most meats, certain egg products, and most alcoholic beverages.

These products are regulated by the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), which requires that any ingredient be declared in the labeling only by its common or usual name.

This concerns labeling for ingredients present unintentionally as a consequence of cross-contact or cross-contamination at any point along the food chain (during raw material transportation, storage or handling, due to shared equipment for processing and packaging, etc.).

Sublingual immunotherapy, in which the allergenic protein is held in the mouth under the tongue, has been approved for grass and ragweed allergies, but not yet for foods.