Mines in the Battle of Messines (1917)

Before the attack, General Sir Charles Harington, Chief of Staff of the Second Army, told the press, "Gentlemen, I don't know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography".

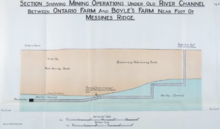

[3][b] The concept of a deep mining offensive was devised in September 1915 by the Engineer-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), Brigadier George Fowke, who proposed to drive galleries 18–27 m (60–90 ft) underground.

Fowke had been inspired by the thinking of Major John Norton-Griffiths, a civil engineer, who had helped form the first tunnelling companies and introduced the quiet cut-and-cover technique.

To overcome the technical difficulties, two military geologists assisted the miners from March, including Edgeworth David, who planned the system of mines.

[11] On 27 August, the Germans set a camouflet, which killed four men and wrecked the gallery for 120 m (400 ft); the mine had been charged and the explosives were left in the chamber.

[13] The BEF miners eventually completed a line of deep mines under Messines Ridge that were charged with 454 t (447 long tons) of ammonal and gun cotton.

[12][17][18] Birdcage 1–4 on the extreme southern flank in the II Anzac Corps area, were not required because the Germans made a local retirement before 7 June.

The evening before the attack, Harington, the Second Army Chief of Staff, remarked to the press, "Gentlemen, we may not make history tomorrow, but we shall certainly change the geography".

[20] The divisional commanders were encouraged by a report by Füßlein on 28 April, that the counter-mining had been such a success, particularly recently that A subterranean attack by mine-explosions on a large scale beneath the front line to precede an infantry assault against the Messines Ridge was no longer possible.

[21] On 19 May, the 4th Army concluded that the greater volume of British artillery fire was retaliation for the increase in German bombardments and although defensive preparations were to continue, no attack was considered imminent.

[21] On 24 May, Füßlein was more optimistic about German defensive measures and Laffert wrote later, that the possibility of mine explosions was thought remote and if encountered they would have only local effect, as the front trench system was lightly held.

Other officers like Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant-Colonel) Wetzell and Oberst (Colonel) Fritz von Lossberg, wrote to OHL warning of the mine danger and the importance of forestalling it by a retirement; they were told that it was a matter for the commanders on the spot.

[22] The British artillery fire lifted half an hour before dawn and as they waited in the silence for the offensive to begin, some of the troops reportedly heard a nightingale singing.

Reports suggested that the sound was heard in London and Dublin; at the Lille University geology department, the shock wave was mistaken for an earthquake.

In an after-action report, Laffert wrote that had the extent of the mine danger been suspected, a withdrawal from the front trench system to the Sonne Line, half-way between the first and second positions, would have been ordered before the attack, since the cost inflicted on the British by having to fight for the ridge justified its retention.