Minoan pottery

Its restless sequence of quirky maturing artistic styles reveals something of Minoan patrons' pleasure in novelty while they assist archaeologists in assigning relative dates to the strata of their sites.

Pots that contained oils and ointments, exported from 18th century BC Crete, have been found at sites through the Aegean islands and mainland Greece, in Cyprus, along coastal Syria and in Egypt, showing the wide trading contacts of the Minoans.

Several pottery shapes, especially the rhyton cup, were also produced in soft stones such as steatite, but there was almost no overlap with metal vessels.

The traditional chronology for dating Minoan civilization was developed by Sir Arthur Evans in the early years of the 20th century AD.

[2] Little is known about the way the pottery was produced, but it was probably in small artisanal workshops, often clustered in settlements near good sources of clay for potting.

For many, potting may well have been a seasonal activity, combined with farming, although the volume and sophistication of later wares suggests full-time specialists, and two classes of workshop, one catering to the palaces.

Archaeologists seeking to understand the conditions of production have drawn tentative comparisons with aspects of both modern Cretan rural artisans and the better-documented Egyptian and Mesopotamian Bronze Age industries.

The potter's wheel appears to have been available from the MM IB, but other "handmade" methods of forming the body remained in use, and were needed for objects with sculptural shapes.

The excavation of an abandoned LM kiln at Kommos (the port of Phaistos), complete with its "wasters" (malformed pots), is developing understanding of the details of production.

[8] Early Minoan pottery is broadly characterized by a large number of local wares with frequent Cycladic parallels or imports, suggesting a population of checkerboard ethnicity deriving from various locations in the eastern Aegean and beyond.

[citation needed] Early Minoan pottery, to some extent, continued, and possibly evolved from, the local Final Neolithic[9] (FN) without a severe break.

[14] These cooking tripods were made from red firing clay with rock fragments to create the coarse touch that these pots had.

These pots are from the north and northeast of Crete and appear to be modeled after the Kampos Phase of the Grotta-Pelos early Cycladic I culture.

The painted parallel-line decoration of Ayios Onouphrios I Ware was drawn with an iron-red clay slip that would fire red under oxidizing conditions in a clean kiln but under the reducing conditions of a smoky fire turn darker, without much control over color, which could range from red to brown.

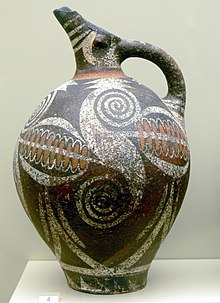

The EM IIA and IIB Vasiliki Ware, named for the Minoan site in eastern Crete,[19] has mottled glaze effects, early experiments with controlling color, but the elongated spouts drawn from the body and ending in semicircular spouts show the beginnings of the tradition of Minoan elegance (Examples 1, Examples 2).

In north central Crete, where Knossos was to emerge, there is little similarity: dark on light linear banding prevails; footed goblets make their appearance (Example).

The rise of the Minoan palaces at Knossos and Phaistos and their new type of urbanized, centralized society with redistribution centers required more storage vessels and ones more specifically suited to a range of functions.

In the palace workshops, the introduction from the Levant of the potter's wheel in MM IB enabled perfectly symmetrical bodies to be thrown from swiftly revolving clay.

[20] The well-controlled iron-red slip that was added to the color repertory during MM I could be achieved only in insulated closed kilns that were free of oxygen or smoke.

Knossos had extensive sanitation, water supply and drainage systems,[21] which is evidence that it was not a ceremonial labyrinth or large tomb.

It is the first of the virtuoso polychrome wares of Minoan civilization, though the first expressions of recognizably proto-Kamares decor predate the introduction of the potter's wheel.

)[citation needed] The floral style depicts palms and papyrus, with various kinds of lilies and elaborate leaves.

[citation needed] LMI marks the highwater of Minoan influence throughout the southern Aegean (Peloponnese, Cyclades, Dodecanese, southwestern Anatolia).

Fluent movemented designs drawn from flower and leaf forms, painted in reds and black on white grounds predominate, in steady development from Middle Minoan.

In LMIB there is a typical all-over leafy decoration, for which first workshop painters begin to be identifiable through their characteristic motifs; as with all Minoan art, no name ever appears.

The Marine Style is more free flowing with no distinct zones, because it shows sea creatures as floating, as they would in the ocean.

Ceramic is not the only material used: breccia, calcite, chlorite, schist, dolomite and other colored and patterned stone were carved into pottery forms.

In the late manifestation of the palace style, fluent and spontaneous earlier motifs stiffened and became more geometrical and abstracted.

(Example) Minoan wares were already familiar from finds on the Greek mainland, and export markets like Egypt, before it was realized that they came from Crete.

Using a drawing of the "Contents of the Tomb of the Tripod Hearth" at Zafer Papoura from Evans' Palace of Minos,[32] which depicts LM II bronze vessels, many in the forms of ceramic ones, Ventris and Chadwick[33] were able to make a few new correlations.