Early Nationalists

Although they asked for constitutional and other reforms within the framework of British rule, they had full faith in that nation's sense of justice and fair play.

Influenced by western thought, culture, education, literature and history, the demands of the early nationalists were not considered extreme but of a relatively moderate nature.

[6][8] The Early Nationalists believed in patience and conciliation rather than confrontation, adopting orderly progress and constitutional means to realise their aims.

To educate the people, to arouse political consciousness, and to create powerful public opinion in favour of their demands they organised annual sessions.

They created a national awakening among the people that made Indians conscious of the bonds of common political, economic, and cultural interests that united them.

[8][11] The Early Nationalists demanded the Abolition of the Preventive Detention Act and restoration of individual liberties and right to assemble and to form associations.

[8] The methods used by the Early Nationalists of passing resolutions and sending petitions were seen as inadequate by critics who argued that they depended on the generosity of the British instead of relying on their own strength and directly challenging colonial rule.

[6][8] The Early Nationalists failed to draw the masses into the mainstream of the national movement such that their area of influence remained limited to urban educated Indians.

The Nationalists were invited to a garden party held by the Viceroy of India, Lord Dufferin in Calcutta in 1886 and another hosted by the Governor of Chennai in 1887.

Official attitudes soon changed; Lord Dufferin tried to divert the National Movement by suggesting to Allan Hume that the Early Nationalists should devote themselves to social rather than political affairs.

[17][19] Some of the younger elements within the Indian National Congress were dissatisfied with the achievements of the Early Nationalists and vociferous critics of the methods of peaceful constitutional agitation that they promulgated.

[9] Young members advocated the adoption of European revolutionary methods to counter British colonial rule while mainstream Early Nationalists remained loyal to the Crown, with their desire to regain self-government lacking conviction.

[6][8] The most prominent leaders of the Assertive Nationalists were Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai and Bipin Chandra Pal, who are known collectively as the Lal-Bal-Pal trio.

While the Early Nationalists moved towards the formation of an all-India political body, Englishman A. O. Hume, a retiree from the Indian Civil Service, saw the need for an organisation that would draw the government's attention to current administrative drawbacks and suggest the means to rectify them.

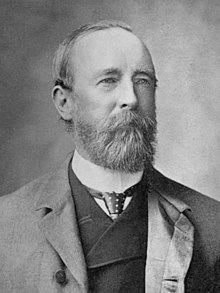

[17] Dadabhai Naoroji, popularly known as the "Grand Old Man of India",[21] took an active part in the foundation of the Indian National Congress and was elected its President thrice, in 1886, 1893 and after the Moderate phase in 1906.