Molecular cloud

Molecular hydrogen is difficult to detect by infrared and radio observations, so the molecule most often used to determine the presence of H2 is carbon monoxide (CO).

[1] Within molecular clouds are regions with higher density, where much dust and many gas cores reside, called clumps.

These clumps are the beginning of star formation if gravitational forces are sufficient to cause the dust and gas to collapse.

[2] The history pertaining to the discovery of molecular clouds is closely related to the development of radio astronomy and astrochemistry.

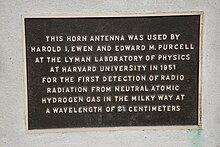

During World War II, at a small gathering of scientists, Henk van de Hulst first reported he had calculated the neutral hydrogen atom should transmit a detectable radio signal.

Once the war ended, and aware of the pioneering radio astronomical observations performed by Jansky and Reber in the US, the Dutch astronomers repurposed the dish-shaped antennas running along the Dutch coastline that were once used by the Germans as a warning radar system and modified into radio telescopes, initiating the search for the hydrogen signature in the depths of space.

Using the radio telescope at the Kootwijk Observatory, Muller and Oort reported the detection of the hydrogen emission line in May of that same year.

[4] Once the 21-cm emission line was detected, radio astronomers began mapping the neutral hydrogen distribution of the Milky Way Galaxy.

[4] Following the work on atomic hydrogen detection by van de Hulst, Oort and others, astronomers began to regularly use radio telescopes, this time looking for interstellar molecules.

In 1963 Alan Barrett and Sander Weinred at MIT found the emission line of OH in the supernova remnant Cassiopeia A.

[1] More interstellar OH detections quickly followed and in 1965, Harold Weaver and his team of radio astronomers at Berkeley, identified OH emissions lines coming from the direction of the Orion Nebula and in the constellation of Cassiopeia.

[4] In 1968, Cheung, Rank, Townes, Thornton and Welch detected NH₃ inversion line radiation in interstellar space.

The solution to this problem came when Arno Penzias, Keith Jefferts, and Robert Wilson identified CO in the star-forming region in the Omega Nebula.

[5] Within the Milky Way, molecular gas clouds account for less than one percent of the volume of the interstellar medium (ISM), yet it is also the densest part of it.

[8] Cosmic dust and ultraviolet radiation emitted by stars are key factors that determine not only gas and column density, but also the molecular composition of a cloud.

The dissociation caused by UV photons is the main mechanism for transforming molecular material back to the atomic state inside the cloud.

Astronomers have observed the presence of long chain compounds such as methanol, ethanol and benzene rings and their several hydrides.

Their short life span can be inferred from the range in age of young stars associated with them, of 10 to 20 million years, matching molecular clouds’ internal timescales.

Some astronomers propose the molecules never froze in very large quantities due to turbulence and the fast transition between atomic and molecular gas.

[14][13] Once a molecular cloud assembles enough mass, the densest regions of the structure will start to collapse under gravity, creating star-forming clusters.

These are a class of variable stars in an early stage of stellar development and still gathering gas and dust from the cloud around them.

Continuous accretion of gas, geometrical bending, and magnetic fields may control the detailed fragmentation manner of the filaments.

[21] Recent studies have suggested that filamentary structures in molecular clouds play a crucial role in the initial conditions of star formation and the origin of the stellar IMF.

The concentration of dust within molecular cores is normally sufficient to block light from background stars so that they appear in silhouette as dark nebulae.

[25]Isolated gravitationally-bound small molecular clouds with masses less than a few hundred times that of the Sun are called Bok globules.