Molecular dynamics

However, long MD simulations are mathematically ill-conditioned, generating cumulative errors in numerical integration that can be minimized with proper selection of algorithms and parameters, but not eliminated.

MD was originally developed in the early 1950s, following earlier successes with Monte Carlo simulations—which themselves date back to the eighteenth century, in the Buffon's needle problem for example—but was popularized for statistical mechanics at Los Alamos National Laboratory by Marshall Rosenbluth and Nicholas Metropolis in what is known today as the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm.

I tried to do this in the first place as casually as possible, working in my own office, being interrupted every five minutes or so and not remembering what I had done before the interruption.Following the discovery of microscopic particles and the development of computers, interest expanded beyond the proving ground of gravitational systems to the statistical properties of matter.

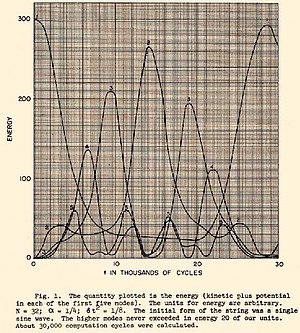

In an attempt to understand the origin of irreversibility, Enrico Fermi proposed in 1953, and published in 1955,[3] the use of the early computer MANIAC I, also at Los Alamos National Laboratory, to solve the time evolution of the equations of motion for a many-body system subject to several choices of force laws.

[5] In 1964, Aneesur Rahman published simulations of liquid argon that used a Lennard-Jones potential; calculations of system properties, such as the coefficient of self-diffusion, compared well with experimental data.

[12][13] First used in theoretical physics, the molecular dynamics method gained popularity in materials science soon afterward, and since the 1970s it has also been commonly used in biochemistry and biophysics.

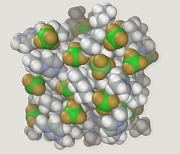

MD is frequently used to refine 3-dimensional structures of proteins and other macromolecules based on experimental constraints from X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy.

In principle, MD can be used for ab initio prediction of protein structure by simulating folding of the polypeptide chain from a random coil.

The results of MD simulations can be tested through comparison to experiments that measure molecular dynamics, of which a popular method is NMR spectroscopy.

[18] For example, Pinto et al. implemented MD simulations of Bcl-xL complexes to calculate average positions of critical amino acids involved in ligand binding.

[19] Carlson et al. implemented molecular dynamics simulations to identify compounds that complement a receptor while causing minimal disruption to the conformation and flexibility of the active site.

[20] An important factor is intramolecular hydrogen bonds,[21] which are not explicitly included in modern force fields, but described as Coulomb interactions of atomic point charges.

Finally, van der Waals interactions in MD are usually described by Lennard-Jones potentials[22][23] based on the Fritz London theory that is only applicable in a vacuum.

[citation needed] However, all types of van der Waals forces are ultimately of electrostatic origin and therefore depend on dielectric properties of the environment.

A variety of thermostat algorithms are available to add and remove energy from the boundaries of an MD simulation in a more or less realistic way, approximating the canonical ensemble.

The Berendsen thermostat might introduce the flying ice cube effect, which leads to unphysical translations and rotations of the simulated system.

Most classical force fields implicitly include the effect of polarizability, e.g., by scaling up the partial charges obtained from quantum chemical calculations.

But molecular dynamics simulations can explicitly model polarizability with the introduction of induced dipoles through different methods, such as Drude particles or fluctuating charges.

In excited states, chemical reactions or when a more accurate representation is needed, electronic behavior can be obtained from first principles using a quantum mechanical method, such as density functional theory.

Due to the cost of treating the electronic degrees of freedom, the computational burden of these simulations is far higher than classical molecular dynamics.

Ab initio quantum mechanical and chemical methods may be used to calculate the potential energy of a system on the fly, as needed for conformations in a trajectory.

A significant advantage of using ab initio methods is the ability to study reactions that involve breaking or formation of covalent bonds, which correspond to multiple electronic states.

In more sophisticated implementations, QM/MM methods exist to treat both light nuclei susceptible to quantum effects (such as hydrogens) and electronic states.

Implementation of such approach on systems where electrical properties are of interest can be challenging owing to the difficulty of using a proper charge distribution on the pseudo-atoms.

But very coarse-grained models have been used successfully to examine a wide range of questions in structural biology, liquid crystal organization, and polymer glasses.

Machine Learning Force Fields] (MLFFs) represent one approach to modeling interatomic interactions in molecular dynamics simulations.

MLFFs address the limitations of traditional force fields by learning complex potential energy surfaces directly from high-level quantum mechanical data.

Modelling these forces presents quite a challenge as they are significant over a distance which may be larger than half the box length with simulations of many thousands of particles.

Though one solution would be to significantly increase the size of the box length, this brute force approach is less than ideal as the simulation would become computationally very expensive.

Umbrella sampling is used to move the system along the desired reaction coordinate by varying, for example, the forces, distances, and angles manipulated in the simulation.